By Christine Thomas (originally published in Socialism Today, magazine of the Socialist Party in England and Wales)

Eleanor Marx played a pivotal role in the mass strikes in the East End of London in the 19th century and campaigned for a mass workers’ party. She was to the forefront of the struggle for women’s rights and for international solidarity. CHRISTINE THOMAS looks at the life of this socialist pioneer.

The recent publication of Rachel Holmes’ lively and sympathetic biography of Eleanor Marx is another valuable contribution to raising awareness about this fascinating revolutionary woman. (Eleanor Marx: A Life, Bloomsbury Publishing) It is also an opportunity to explore further the interesting times in which she lived and struggled. For many people, Eleanor is known simply as the youngest daughter of the author of Capital, yet she was more than just her father’s daughter. Eleanor Marx was in her own right a leading political activist, writer, speaker, trade unionist, socialist feminist and internationalist in an important period of British history, rich in lessons for political and social struggles today.

From her birth on 16 January 1855 to her untimely death at the age of 43, Eleanor’s life was steeped in politics. By the age of 17 she was, according to her mother, Jenny von Westphalen, “political from top to toe”. Her political activism was first awakened by the struggle in Ireland against imperialist exploitation and oppression. In 1871, at the age of 16, she was not only inspired by the momentous revolutionary uprising of the Communards in Paris but actively involved in helping the many refugees who fled to England after the bloodbath in which 20,000 workers were massacred and thousands imprisoned and deported. One of those who escaped to England was Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, with whom Eleanor had a relationship, helping him to write his seminal history of the Commune. As Holmes points out, for Eleanor, the personal and the political were intrinsically intertwined.

Eleanor was struck by the protagonism of women during the Paris Commune, and both socialist feminism and internationalism were to be defining features of her political life. She participated in the congress of the International Working Men’s Association (the First International), was involved in the founding of the Second, Socialist International in 1889, and played a prominent role in promoting international solidarity with workers in struggle. It was the nationalism and jingoism of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), the first political organisation she joined, which caused her to break with the party after one year (in 1885) and form the Socialist League, together with William Morris and her partner Edward Aveling.

Eleanor was politically active in a period in which women were still denied many basic rights and leading female militants constituted a rare minority in the labour movement. It was also a period of transition, culminating in an explosion of social and industrial struggles, and a transformation of working-class political consciousness. Thanks to the international hegemony of British capitalism and its ability to make economic concessions to a layer of skilled workers – and create a privileged union bureaucracy – the 1860s had been a decade of relative social peace, dominated ideologically by class collaboration. Politically, this found its expression in the Liberal Party which claimed to represent the interests of both workers and employers.

Competition from Europe and America, however, threatened British capitalism’s economic dominance. In 1885, Friedrich Engels, Eleanor’s ‘second father’ and an enormous political influence, wrote: “During the period of England’s industrial monopoly the English working class have to a certain extent shared in the benefits… These benefits were very unequally parcelled out… the privileged minority pocketed most, but even the great mass had at least a temporary share now and then… With the breakdown of that monopoly the English working class will lose that privileged position… And that is the reason why there will be socialism again in England”. (The Commonweal, paper of the Socialist League)

Eleanor was to the forefront in promoting the ideas of socialism among working-class people. She popularised Karl Marx’s economic theories, spoke about women’s oppression, trade unionism, internationalism and the importance of independent working-class political representation. Returning from an eye-opening three-month speaking tour of the USA, she and Aveling toured the Radical Clubs in London’s East End. They addressed working men about the social, industrial and political situation in America, and called for the creation of a new working-class party; in the words of Engels, an “English Labour Party with an independent class programme”, which would provide workers with a political alternative to the Liberals.

This was essentially propaganda work, sowing the seeds for future explosive events which would help transform the political situation. In the mid- to late-1880s the forces of socialism were still small and relatively divorced from the day-to-day struggles of working-class people. Those organisations which did exist were riven with ideological, tactical and personal divisions. “There are two main sources of dispute”, said William Morris: “We cannot agree as to what is likely to be the precise social system of the future and we cannot agree as to the best means of attaining it”. Eleanor was to break with Morris and the Socialist League in 1888, four years after its foundation, because of his opposition to standing candidates in parliamentary elections. Her Bloomsbury branch of the Socialist League then became the Bloomsbury Socialist Society through which she and Aveling continued to agitate for a workers’ party.

Mass poverty

The ‘great depression’, which erupted in 1873 and lasted until 1896, with brief and weak periods of recovery, opened up a new stage of economic and social crisis for British capitalism and was to have an enormous effect on class consciousness and organisation. The economic depression reached its nadir in 1886/87 with especially devastating consequences for the poor of London: 35% of the population of the East End lived in conditions of abject misery.

Eleanor wrote of the thousands who in a normal winter could just keep going but were now starving in filthy hovels or in ditches in driving rain. She witnessed first-hand the terrible human suffering, writing to her sister Laura: “One room especially haunts me. Room! – cellar, dark underground – in it a woman lying on some sacking and a little straw, her breast half eaten away with cancer. She is naked but for an old red handkerchief over her breast and a bit of old sail over her legs. By her side a baby of three and other children – four of them… The husband tries to ‘pick up’ a few pence at the docks”.

Despite this awful destitution the unemployed began to organise. Their daily meetings and protests were subject to severe state repression which was being stepped up in an attempt to cower workers and stamp out growing social protest. “The State”, wrote Eleanor in 1885, “is now a force-organisation for the maintenance of the present conditions of property and social rule”. Bloody Sunday (13 November 1887) is the most infamous example from that time of the brutality meted out by the state against those who tried to rise up against oppression, exploitation and poverty. The police repeatedly charged a mass demonstration in Trafalgar Square. Demonstrators were trampled by horses and viciously beaten, 200 were hospitalised, 160 jailed, and three later died of their injuries. Eleanor was herself a victim of police brutality on that day, and on other free speech protests.

Fighting women’s oppression

It was through the unemployed protests that Eleanor really got to know the horrendous conditions suffered by working-class people in the East End of London. The industrial wave which later exploded there, with the most exploited and downtrodden sections of the class at its head, enabled her to link the theory of class struggle with the practice. The same was true regarding the question of women’s oppression. Her profound interest led her, in 1885, to co-write with Aveling ‘The Woman Question: From a Socialist Point of View’, the first pamphlet written by a socialist woman on this issue. Eleanor had studied August Bebel’s ‘Women and Socialism’, first published in England in 1885. She had also worked closely with Engels in the production of the Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), based on the notes of the deceased Marx and the work of Lewis Henry Morgan.

“Marx and Morgan’s was the theory, Eleanor’s life was the practice”, writes Hughes, who believes that Engels drew on Eleanor’s own contradictory personal situation as a ‘New Woman’ in a still intensely patriarchal society. Eleanor understood that the capitalist system oppressed women of all classes, denying them, among other things, the right to vote and access to higher education and the professions. She recognised the value of cross-class alliances of women – for example, in the campaign for repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, under which women could be arbitrarily detained, confined in hospital and subject to intimate abuse merely on the suspicion of being a prostitute.

But she criticised the limited ‘bourgeois idea’ of ‘women’s rights’, declaring: “Those who attack the present treatment of women without seeking for the cause of this in the economics of our latter-day society are like doctors who treat a local infection without enquiring into the general bodily health”. Eleanor and Aveling emphasised the class character of women’s oppression, rooted not in the natures of individual women or men, but in the very structures of capitalist society. The poverty wages paid to women serve directly to increase profits for the capitalists, placing downward pressure on men’s wages, while inequality in the workplace divides workers and weakens the class struggle.

Therefore, the fight against low and unequal pay is a vital fight of all workers: “With the proletarian woman… it is a struggle of the woman with the man of her own class against the capitalist class”. Without economic autonomy women cannot be liberated from oppression: “We must understand that the real cause of women’s enslaved position is her economic dependence upon man and that her ‘emancipation’ means nothing but economic freedom”. However, while higher wages and equal pay were crucial demands to be fought for by women and men together in the labour movement, for Eleanor the ‘woman question’ was not merely economic but linked to “the organisation of society as a whole”. “Without that larger social change women will never be free”. And without the participation of working-class women in the struggle for their own emancipation and for an end to capitalism, a new, free and equal society would be impossible.

The double burden

Personal relationships and women’s opportunities in life are conditioned by wider social inequalities. “Our marriages, like our morals, are based on commercialism”, she wrote. Eleanor was particularly drawn to the Norwegian playwright, Henrik Ibsen, and his portrayal of the conflict felt by women trapped in unhappy and unfulfilling marriages. If both sexes are incomplete relationships suffer, she argued. Eleanor and Aveling laid great emphasis on the ‘sex instinct’: the need for women as well as men to enjoy sexual satisfaction and the damaging consequences for women’s mental, physical and emotional health when sexual desire is ungratified. They stressed the importance of sex education free from moral constraints. Only when men and women “discuss the sexual question in all its bearings, as free human beings… will there be any hope of its solution”.

Eleanor personally experienced society’s sexual double standards when she decided to defy social norms and live with Aveling without getting married (he falsely claimed to be already married to a woman who refused to grant him a divorce). While Eleanor as a woman felt the need to write to all her friends to explain her decision, expecting some to break off their friendship as a result of her actions, Aveling as a man felt no need to do the same. They both wrote about the double burden experienced by working-class women who were “still the childbearer, the housewarder”. “The man, worn out as he may be by labour, has the evening in which to do nothing. The woman is occupied until bedtime comes. Often with young children her toil goes far into, or all through the night”.

While she was in the USA, Eleanor called for working men to give women a helping hand with children and the home so that their wives could play a full role in the workers’ movement. And working women should demand that potential lovers show them their union card or, if not, show them the door. Eleanor had no children (she wanted them, Aveling procrastinated) and Aveling never tried to place restrictions on her political and leisure activities; on the contrary, he shared and encouraged them. Nonetheless, it was she who, according to the prevailing norms, was expected to run the household: “How I wish people didn’t live in houses and didn’t cook, and bake, and wash and clean”. “Who is the fiend that invented housekeeping? I hope his invention may plague him in another world”.

Eleanor had had an unconventional upbringing and education for a woman of her times. She was economically independent of Aveling (he leeched off her) and refused to accept Engels’ financial help (unlike her two older sisters, Jenny and Laura). Instead, she earned her own income, teaching, writing, translating and editing. At the same time, she was able to pursue her interests in the theatre and the arts, and to help bring these cultural pursuits to the working class, helping to broaden the horizons of workers who had been denied a formal education.

She was almost unique at the time in being both a leading female socialist and trade unionist. And yet, as a woman, she was not able to completely escape the conflicting pressures of family and society. In fact, her first attempt at personal and economic autonomy failed, resulting in anorexia and a breakdown, an example of the so-called ‘hysteria’ suffered by so many women of her class whose needs and expectations were frustrated or came into conflict with social reality. These contradictions were also evident in her relationship with Aveling with whom she stayed loyally for 14 years, despite his being a needy, selfish user, and despite his numerous affairs, deceptions and humiliations.

East End strikes

The women workers who went on strike at the Bryant and May match factory, in 1888, sparked the huge strike and unionisation wave which swept east London and dramatically changed both the industrial and political landscape. From these class struggles a new form of militant trade unionism was born, challenging the class collaboration of the craft unions. Class and socialist consciousness grew significantly and the idea of independent working-class representation, which socialists like Eleanor had been advocating without any concrete results, now had a mass, receptive audience. The East End was home to the ‘sweated industries’ and the growth in factories and workplaces where unorganised semi-skilled and unskilled workers toiled for long hours, in harmful conditions, for starvation wages.

Many of these were women – a third of the workforce in 1888 – often with children, earning around 50% of the already abysmally low male wage. Eleanor was involved in all the main struggles that took place in the East End in the crucial year of 1889, struggles which involved male and female workers: gas workers and dockers, workers in the industrial hellhole known as Silvertown. She was approached for help by female shop assistants, onion skinners at Crosse & Blackwell, and sweet makers at Barratts, as well as by rail workers. The gas workers, who were considered seasonal and unskilled, often worked for up to 18 hours a day in addition to travel (normally by foot) to and from work. In Silvertown, workers slaved for a minimum of 80 hours a week, inhaling poisonous fumes in the place where they both worked and ate. “To go to the docks”, wrote Eleanor, “is enough to drive one mad. The men fight and push and hustle like beasts – not men – and all to earn at best 3d or 4d an hour!”

Engels wrote: “That these poor famished broken down creatures… should organise for resistance, turn out 40-50,000 strong, draw after them into the strike all and every trade of the East End in any way connected with shipping, hold out above a week, and terrify the wealthy and powerful dock companies – that is a revival I am proud to see”. Here were the lowest of the low, the super-exploited workers deemed unorganisable by the existing trade union leaders, rising up against all the odds, striking and forming new combative unions, prepared to resist and actively take on the bosses’ assaults on their jobs, wages and working conditions. Within two weeks over 3,000 joined the gas workers’ union. “Never before had men responded like they did. For months London was ablaze”, declared union leader Will Thorne.

It was not, however, a completely straightforward process. There had been several failed attempts to form a union of gas workers. Critical to the change in consciousness, in Thorne’s eyes, were “the long years of socialist propaganda amongst the underpaid and oppressed workers”. The gas workers were victorious, securing a reduction in the working day to eight hours. The Silvertown workers, on the other hand, were starved back to work after twelve weeks of bitter struggle, mainly due to a lack of solidarity from the skilled engineers and carpenters. But even from defeats unions were formed and the old, more established organisations were not immune from these historic events. In one year, total union membership more than doubled.

“It was a time when one socialist, active and determined, giving assistance to the unskilled workers, was worth 20 discussing revolutionary tactics in their private clubrooms”, said William Morris. There is no doubt that socialist ‘agitators’ like Eleanor were giving invaluable backup and support to workers in struggle, and that interest in socialism was growing. “The other night I was up at the committee rooms talking to the men [gas workers], and one and all declared themselves Socialists”, wrote Eleanor to her sister, Laura. “The masses here are not yet socialist. But on the way towards it, and are already so far that they will not have any but socialist leaders”, commented Engels. These activists, however, were intervening primarily as individuals, not as members of a party striving to link the day-to-day struggles of workers with a revolutionary transformation of society.

Eleanor eventually re-joined the SDF because she considered it to be the socialist organisation with the most influence, but she was under no illusions about its real political character. New Unionism exposed the SDF’s sectarian approach to the trade unions. Its new programme, drawn up at the height of the struggle, did not even refer to them! The SDF, Engels argued, was a propaganda organisation, advocating a dogmatic distortion of Marxism which denied the importance of the class struggle in overthrowing capitalism and failed to “fasten on to the real needs of people”. Nonetheless, most of the new union organisers passed through its ranks and it was responsible for introducing tens of thousands to the general ideas of socialism. Eleanor’s own approach was very different. Another biographer, Yvonne Kapp, summed it up thus: “She was zealous to work for any and every practical aim; to agitate for the total overthrow of the system without brushing aside a single immediate demand for which the working class were prepared to fight”. (Eleanor Marx, Volume II, The Crowded Years)

Linking political and industrial action

Thorne and the dockworkers’ leader, Ben Tillet, described how Eleanor would work long hours in support of the gas workers, getting up early in the morning and walking home late at night. She addressed mass meetings and demonstrations of tens of thousands of workers, becoming one of the most talented and sought after speakers in the labour movement. In Silvertown she would get up on tables and chairs in pubs to speak to workers about the strike. But she was also hyperactive behind the scenes: raising money, drafting rules for the gas workers’ union, helping Thorne with the accounts, showing the same dynamism, dedication and tirelessness she employed in her work for the socialist organisations she belonged to. The strike wave of unskilled and semi-skilled workers turned Eleanor into a respected, national trade union leader. She was elected to the national executive of the gas workers’ union at its first conference in 1890 and became leader of the first women’s branch of the union which was formed from the Silvertown strike.

The central organising demand of the new union strike wave was the eight-hour day, around which workers were also mobilising internationally. This had a critical relevance for unskilled and semi-skilled workers who often had no contracted limit on the hours which they worked. Women workers were particularly affected. But the demand was opposed by the craft union leaders who argued against the government intervening when workers could ‘do it for themselves’. It was OK for ‘defenceless women and children’ (and miners) but not the rest of the working class. The unions must stay out of politics. Eleanor saw no artificial division between industrial and political action.

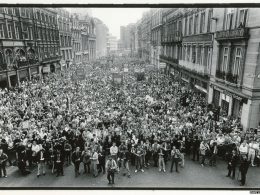

The demand for a legal eight-hour day served both to mobilise workers and to raise political consciousness. The gas workers had clearly shown that self-organisation, collective action and solidarity could result in victory against individual employers. But legislation was also needed to reinforce those victories, prevent backsliding and to defend the millions who remained unorganised. The founding Paris congress of the Second International declared May Day to be an annual day of international solidarity: 250,000 workers rallied in Hyde Park in 1890 to demand that the government establish the eight-hour working day as a legal limit.

Eleanor played a central role in organising the protest and was one of the main speakers. Her speech to the mass rally clearly showed the transitional approach which she adopted in her politics. “I am speaking this afternoon not only as a trade unionist but as a socialist”, she declared. “Socialists believe that the eight-hour day is the first and most immediate step to be taken, and we aim at a time when there will no longer be one class supporting two others, but the unemployed both at the top and at the bottom of society will be got rid of. This is not the end but the beginning of the struggle”.

Working-class representation

The Eight Hours League was later established and discussed standing in elections. The political wind was finally turning. In 1892, in a very significant vote, the gas workers’ conference in Plymouth agreed to present candidates for all local and parliamentary elections. Keir Hardie had already founded the Scottish Labour Party in 1888 and, at the 1892 TUC congress, chaired a meeting of delegates who supported the idea of founding an independent labour party. Independent labour organisations were also springing up in the industrialised north of England as workers learnt from bitter strikes that they had politically nothing in common with the Liberal-supporting bosses. It was from here that the Independent Labour Party (ILP) was formed in 1893. Unlike the SDF, the ILP understood the importance of the trade unions in the struggle to change society. But while its programme was broadly anti-capitalist, it was ideologically confused, with a strong reformist element. This prompted the SDF to stand aside from the ILP in ‘benevolent neutrality’, criticising in sectarian fashion its failure to explicitly call itself a socialist party.

While clear about the political weaknesses of the ILP, Eleanor was critical of the SDF’s stance: “We are still not able to speak in the name of a British Labour Party. Such a party, in the sense of an absolute unity of programme and method, does not exist here… But it has also to be noted that a new organisation, the Independent Labour Party has been formed… and is evidence that the class-consciousness of the workers is passing from the dim to the clear stage”. Engels also considered the birth of the party, despite its inadequacies, an important advance for the working class. It was born out of class struggle and behind it “stand the masses”. The role of socialists was to “represent the movement of the future in the movement of the present”.

The ILP did not become a mass workers’ party, arising as the industrial movement was ebbing. But it did become a constituent part of the Labour Representation Committee formed in 1900 (becoming the Labour Party in 1906) which grew from the counter-offensive that the capitalist class launched against the workers’ movement. The capitalists ‘reorganised’ industry, introducing new mass production techniques while attacking the wages and conditions of skilled and unskilled workers.

Eleanor did not live to see those events, but she had played a crucial role in paving the way for the eventual creation of an independent workers’ party. Its leadership reflected Liberal pro-capitalist ideology but, at the same time, it had a mass base rooted in the working class. Had she not died so young, said Thorne, Eleanor “would have been a greater women’s leader than the greatest of contemporary women”.

Her death, in 1898, is still shrouded in mystery and controversy. The coroner presented a verdict of suicide as a consequence of drinking prussic acid. Her friends blamed Aveling, the main financial beneficiary of her death, for being indirectly or even directly responsible. It was a period of emotional turmoil in her life. She had recently found out that Aveling had secretly married a young actress. With Engels’ death in 1895 it was also revealed that Freddy Demuth was not, as she had always suspected, the illegitimate child of Engels but of Marx.

She had had previous bouts of depression. And yet ‘work’ had always pulled her back. We will probably never know what really happened. But her political legacy survives and is clearly invaluable for revolutionary socialists involved in the struggles being waged today. It can be seen in the fight of low-paid workers in the US for union organisation and a minimum wage of $15 an hour, the global struggles by women against discrimination and oppression, and the crucial campaigns to build new mass workers’ parties internationally, as steps towards the socialist transformation of society.