The following article was first published in issue #18 of Socialist Alternative, the theoretical magazine of Socialist Party.

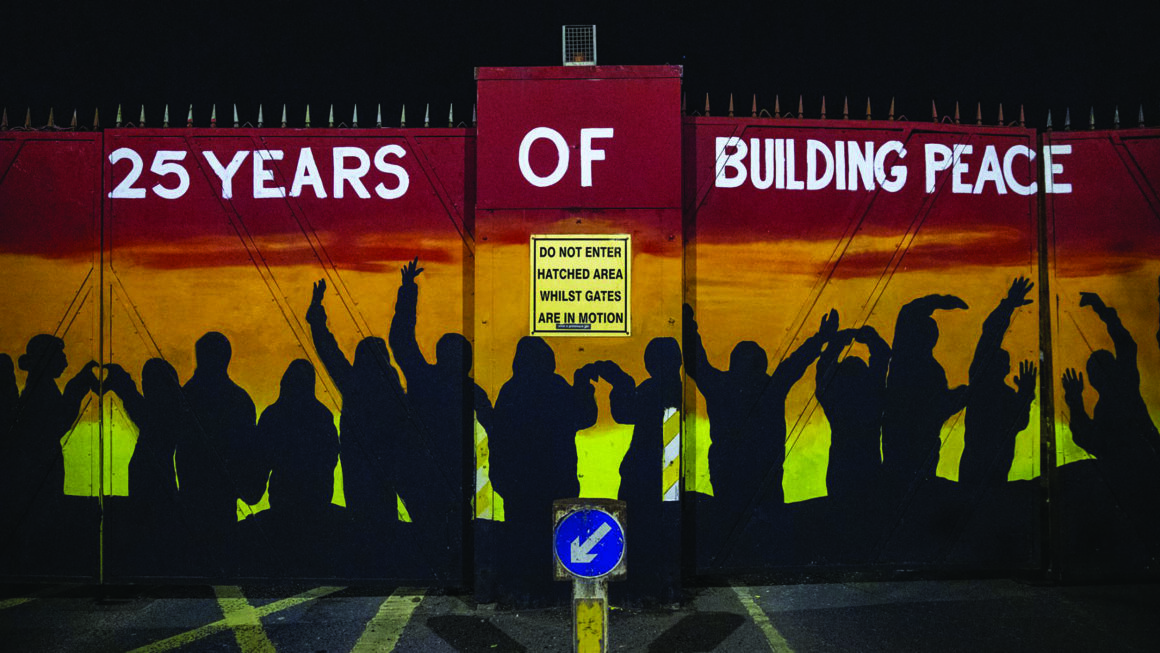

In the previous issue of this journal we republished an article by Peter Hadden originally published in May 1998 entitled ‘Will the Agreement Bring Peace?’ Here, Ann Orr and Paudie McKee show how the analysis in that article has been borne out over the 25 years since it was written, as reflected sharply in the political and social crises that currently rack the North. The Good Friday Agreement was and remains incapable of overcoming sectarian division and bringing lasting peace. In fact, its inherent flaws mean that without a struggle by the working class to bring about genuine unity between Protestant and Catholic communities, the trajectory in the North is ultimately towards further division and a return to conflict.

25 years on – a different world

War-weariness among ordinary people after nearly 30 years of the ‘Troubles’ brought about the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in 1998. A consequence of this mood was dramatic developments within key political organisations, including the realisation by important sections of Sinn Féin’s leadership that its military strategy could not succeed in defeating the British state, nor the opposition of one million Protestants to a united Ireland. Reflecting a global trend of social democracy and so-called national liberation movements moving away from socialist rhetoric, a political shift to the right also took place within Sinn Féin.

The international context was also an important factor in shaping the attitude of the British government. The 1990s was a triumphant time for capitalism and the major capitalist powers – considered the unquestionable victors of the Cold War following the collapse of the USSR. This political and ideological momentum reflected itself in different peace agreements worldwide. For Britain, the US’s closest ally, there was a significant prestige element in wanting to “resolve” the Troubles – during which over 3,700 people had been killed.

Twenty five years on, the differences locally and internationally are striking: far from triumphant, capitalism globally, and British capitalism in particular, is mired in profound crisis. Amplified by the Covid pandemic the world economy is still experiencing major shocks. Inter-imperialist tensions and military conflict are back on the agenda. The effects of climate change are increasingly severe, set to worsen drastically in the coming years as the world’s governments stand by and their policies compound the problem. There is a growing sense that the system cannot resolve these issues, nor the every-day oppression faced by so many. The result is political instability, including a rise of reactionary and far-right ideas in many countries, but also of struggle by working-class and young people.

Growing up with the GFA

The GFA was and still is held up by many establishment politicians as the only viable basis for a ‘prosperous’ Northern Ireland free from violence and sectarian division. In reality, young people face a scarred and deeply divided society, with a lack of opportunities and a declining standard of living. All of these provide the basis for sectarian division, racism, gender-based violence and the continuance of paramilitary violence. The recent femicide of Chloe Mitchell and the murder of Lyra McKee in 2019 by the New IRA are stark reminders of this.

The repetition of the process of raising expectations for change and a dashing of hopes has resulted in a new generation of working-class young people frustrated with the reality of Northern Ireland. To a degree, this is illustrated in the beginning of a change in attitudes regarding the GFA. According to a survey by NI Life and Times, support for the agreement is lowest in 18-24-year-olds, with only 12% believing it is the “best basis for governing NI” and 34% stating it is the “best basis but needs changes”, while 22% believe it is “no longer” or “has never been the best basis”.1

Some commentators brush off the growing questions young people have over the GFA as simply being because they did not live through the Troubles, and therefore take for granted the relative peace it has brought. For a minority this may be true, however in the main this is far off the mark. Young people overwhelmingly support the peace process and do not want to see a slide back into violence. Their doubts are based on the reality of the ‘peace process’ failing to deliver on its promises. After 25 years, housing in working-class areas is overwhelmingly segregated, with more peace walls in place now than in 1998. Even though the GFA also included recognition of the importance of facilitating integrated education, only 68 out of the 1,091 schools in the north are integrated, with only 7% of secondary school pupils in integrated schools.

Combined with the segregation of community groups and sports, many young people grow up without knowing, never mind developing meaningful relationships with, people from the other community until they join the workforce or attend university. This is not an accident, or a conscious choice by working-class people, but the product of the Stormont parties’ reliance on sectarian division. Rather than tackle sectarianism, they have institutionalised and weaponised it to their benefit and the detriment of working-class and young people across the North. This is at its most vicious when used to stand over cuts, that increase the hardship of Protestant and Catholic working-class people equally, which has been a constant theme in the 25 years since the GFA.

Decades of neo-liberal policies carried out and sometimes celebrated by the Stormont parties at the behest of Tory and Blairite Labour governments has deepened the economic deprivation in working-class communities. While some multinational companies have set up shop in the North, for the vast majority of the working class and young people their living standards have not improved. Although unemployment is no longer stubbornly above the UK average, the quality of jobs has seen a marked downturn, with well-paid manufacturing jobs being replaced with precarious hospitality and call centre jobs, stagnant wages and poor conditions, with many young people seeing no option but to emigrate.

It is in these conditions, in a divided society, that the naked sectarianism of Stormont politicians can gain an echo. In the most hard-pressed areas, it allows paramilitaries to thrive, recruiting the most alienated and desperate people. In the past 25 years, paramilitary violence has turned inwards for the most part, replacing the sectarian shootings and bombing with criminality and ‘policing’ of their respective communities. Often this takes the form of punishment-beatings and shootings. According to the Safeguarding Board for Northern Ireland 89 young people under the age of 18 have been subject to punishment shootings, with hundreds more being the victims of beatings since the GFA.2

The negative impact on the lives and mental health of the victims, their friends and families cannot be overstated. It is one of the many reasons for the mental health crisis in Northern Ireland, alongside the intergenerational trauma from the legacy of the Troubles, as well as poverty – all worsened by the continual cuts to the NHS and mental healthcare provision, resulting in over 16,000 people languishing on waiting lists for their first appointment. As such, suicide rates in the North are also the highest in the UK, with 14.3 suicides per 100,000 in 2021, which compares with a figure of 10.5 in England and Wales, and 8.2 in the South.3

Shifting attitude of the British ruling class

At all times, British governments have represented their own interests – the interests of British capitalism and imperialism – not the interests of working-class people in the North, Protestant or Catholic. Their approach has modified as these interests also shifted. To solidify the partition of Ireland in the early 20th century, British imperialism whipped up sectarian tensions and divisions in what was coined by Lord Randolph Churchill as “playing the orange card”.4 For a period following the GFA the British government falsely portrayed itself as a neutral arbiter between two opposing sides.

In the 1990s and continuing into the 2000s the desire for greater stability in the North, and thus reduced need for a high and expensive security presence, was widespread among the representatives of British capitalism for reasons of reputation and prestige, as well as a desire to develop the private sector of the economy. They would gladly have withdrawn from Northern Ireland while continuing to benefit economically from a single independent state – a state that would of course not threaten capitalist social structures. However, the conditions they had created over the previous decades meant that this was not possible due to the opposition from the Protestant population in the North – an opposition that has not diminished.

Today, the Tory government continues to defend the interests of British capitalism and the British state, as evidenced for example by their Troubles Legacy bill – designed to protect the state from allegations and prosecutions for killings committed during the Troubles. Tensions and struggles between the main imperialist blocks, Brexit and the pressures towards closer European cooperation in the context of the war in Ukraine are also factors that are impacting the attitude of the British government in relation to the North. In particular, it now fears the breakup of the union with Scotland, which would have significant economic implications and would constitute a massive blow to the prestige of a nation that was once a key imperialist power, but is now a two-bit player in the New Cold War and on the global stage generally.

The Tories have therefore adopted a more stringent opposition to a border poll and the growing calls for Scottish independence. The concern is never for the interests of working-class people, regardless of national identity, but rather what suits the establishment at any given time, regardless of the consequences. The same applies to Rishi Sunak’s deal with the EU: the Windsor Framework. Stabilising the situation in the North is part of the aim, but not out of concern for the living standards of working-class people here, but to ensure the basis is laid for further agreements in the economic and political interests of Britain in the future.

At times the utter lack of understanding and shere disregard towards escalations in sectarianism is exposed. This was the case earlier this year when joint authority (over Northern Ireland by the governments in London and Dublin) was raised. Because the Northern Ireland Office did not immediately rule this out as an option, loyalist paramilitaries threatened to bomb a Southern governmental building – a clear indication of the volatility in the present situation. It is also the case that every action to “resolve” a phase of the conflict has laid the basis for future disagreement. In the same way as its use of sectarianism to fortify partition later meant the British government could not leave the North as it would have liked, it was its decision to institutionalise sectarianism with the GFA and sell it on the basis of conflicting and irreconcilable promises that is now a key reason for its inability to find a way out of this impasse.

GFA – no stable basis for peace

For 35% of the last 25 years, the Stormont Executive has not sat because one of the two main parties refused to participate. This has been a consistent reminder of the shallowness of the agreement. The core of the issue lies in the conflicting national aspirations held by working-class people here – a conflict that on the basis of capitalism cannot be resolved without resorting to some form of coercion. This means either coercing the Catholic population into a Northern Ireland state that has overseen a century of discrimination and repression, or coercion of a future Protestant minority into a united Ireland, which on a capitalist basis would make them an oppressed minority. Neither are resolutions to the issues faced by the working class and neither will overcome divisions. As we wrote in 2018:

“The real reasons for the difficulties in reaching agreement on Brexit […] are fundamentally a consequence of the inability of capitalism to achieve a lasting solution to the national question in Ireland. In the 1980s, The Economist magazine wrote that the Troubles in Northern Ireland were “a problem without a solution”. This seemed a rational conclusion at the time, but then the 1998 Good Friday Agreement gave the appearance of falsifying this prognosis. In fact, the Good Friday Agreement did not represent a solution then or now.”5

Today, 25 years after what was heralded as a groundbreaking peace agreement, the threat of a return to violence and irrevocable collapse of the institutions is more acute than ever. This is recognised by many, including even Brandon Lewis, former NI Secretary (2020-2022), who stated that the peace agreement was “fraying, if not outright broken”.6 The main political parties, as well as the British and Irish governments, are restricted to trying to find a way forward on the basis of the current system. The suggestions vary from a return to some form of power sharing, even if it involves renegotiation of the agreement to include mandatory coalition; to some form of direct rule from Westminster; to joint authority by London and Dublin; to a united Ireland as a result of a border poll. None of which would begin to address the conflicting national aspirations of working-class people. None is a solution to division and conflict.

Only through workers’ unity is real peace possible

As alluded to above, the GFA and the political institutions it created were major prestige projects for the British and also the Irish governments. Tony Blair, the Labour Prime Minister at the time and his Irish counterpart, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, were held up as the men who brought about peace in Northern Ireland. They, alongside US President Bill Clinton, were part of the discussions that culminated in the GFA. How the GFA was reached has far more to do with other factors, however. The context was shaped by a growing realisation that a military defeat of the British army by the IRA was not possible (and vice-versa) on the one hand, and a growing understanding that the situation in Northern Ireland would remain volatile and contrary to the image the UK wanted to portray globally on the other. What Reginald Maudling, the British Home Secretary in 1971, described as “an acceptable level of violence” was also not sustainable, as tensions regularly spiked.7

However, albeit connected to these points, the key factor that pushed for an end to the Troubles and for some political action remained the strong war-weariness among working-class people reflected in the important strikes organised in response to sectarian violence, for example following the Teebane Massacre in 1992 or the 80,000 who protested after the Greysteel Massacre in 1993. These were illustrations of the crucial role of the united working class in challenging the poison of sectarian division and violence.

In the intervening years, while the working class has at different times demonstrated its capacity to come together, we have not yet seen the full potential power of the united working class. This power finds expression in different ways, but most clearly in workplaces and trade union organisations, where workers have won significant victories including on pay in recent months and in repeated defeats of water charges and other austerity measures. We have also seen this unity in joint active movements for abortion rights, LGBTQ rights and in the movements of young people on the climate crisis.

There is an urgent need also for this power to find expression and to be built on a political level. None of the main parties represent the interest of working-class people. They rely on sectarian voting patterns, so none of them has any interest in overcoming sectarian division. To a lesser extent that also applies to Alliance. It is not a “green or orange” party, and presents itself as an alternative to sectarian voting. However, its approach and politics do nothing to overcome sectarian division. In fact, Alliance is the most openly neo-liberal party in Stormont – supporting water charges and “rationalising”, i.e. cuts to public services hitting working-class communities the hardest. Its approach cultivates the conditions in which sectarianism thrives. To challenge this, a new party that can bring together working-class people across the sectarian divide to fight for our common interests is essential.

Such a party would need to be steadfast in its defence of working-class interests, including in actively challenging sectarianism. It would need to adopt a strong stance against all forms of oppression, and support struggles such as the fight against gender-based violence, and for trans rights. Such a force, based on anti-sectarian and anti-capitalist politics could be hugely attractive to young people, giving a voice to their struggles and an arena for organising. It could cohere the resistance of working-class people to the coming onslaught on our public services, jobs and rights, as well as on issues like housing, climate and war.

Such a force needs to be urgently built. It must arise out of the struggles we see in workplaces and in numerous campaigns. The trade union movement, which already organises 250,000 workers from all backgrounds across the North, clearly has a particularly crucial role to play, not only in popularising a call for a new working-class party but in actually bringing this about. It is precisely while engaged in struggles on such issues that the direct experience of fighting together, side by side and in our shared interests, that even deep-seated attitudes, including sectarianism, can be overcome.

The struggle for socialist change

The conflict of national aspirations in the North is irreconcilable on the basis of the capitalist status quo, which will ultimately always involve coercion of one community in some form. To actually resolve the national question means challenging capitalism, fighting for the socialist alternative to this brutal system, and deeply rooting this struggle at all times in building working-class unity across sectarian and all divides. Capitalism’s whole history on this island speaks to its brutal nature, including the violent and divisive role of British imperialism, the exploitation of Ireland for raw materials, food and later also cheap labour sources for manufacturing in Britain’s industrial cities.

Furthermore, in any capitalist society, minorities are at risk of discrimination and oppression. This is also the case in the South, as evidenced by the experience of the Irish Traveller community and also of refugees, with the Fine Gael / Fianna Fail / Green Party coalition government for example deciding they will no longer house refugees from outside of Ukraine.

Removing exploitation and oppression at its root necessitates a struggle for a socialist transformation of society – taking society’s wealth and resources into democratic public ownership and planning their use to meet the needs of all. This can only be achieved through collective struggle of all the exploited and oppressed. Furthermore, unity among working-class people in struggle is precisely how mutual understanding and respect can be attained – providing the basis for a real resolution to the national question.

This is what is contained in our call for a socialist Ireland free from all coercion and in which the working class collectively would guarantee the rights of all minorities. Working-class people of all nationalities have a common cause in opposing capitalist exploitation and likewise in building a socialist society based on equality and freedom. In this vein we furthermore call for a free and voluntary socialist federation of Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales as part of a socialist Europe, with the right to opt out of any arrangement.

Conscious anti-sectarianism vital

The basis was not laid for the resolution of the conflict with the GFA agreement, but instead, as we argued at the time, a certain space was provided for working-class people to push things in a different direction. Since the GFA, workers have also repeatedly stood together in the face of paramilitary threats or violence. This was the case for example when probation workers or translink staff walked out following paramilitary threats against colleagues. It was also evident when people joined vigils and protests in the aftermath of the killing of Lyra McKee in 2019, and most recently when 1,000 people attended a protest called by the Omagh Trade Union Council following the shooting by paramilitaries of an off-duty police officer in front of a busy sports complex. These are some of the powerful moments in which working-class people came together to halt any threat to go back to the dark days of open sectarian conflict.

To truly overcome sectarian division, however, will require more than challenging incidents of escalating tensions and paramilitary violence. Since the GFA there were several moments in which the potential for workers finding a different way forward was posed in outline form. This included 2011, when workers in the public sector stood side by side in their struggle against pension reforms; part of a movement linking with their colleagues across Britain, which at its height saw 2 million workers participate in a strike day in November that year. If the union leaders had not sold out the government could have been forced to scrap its draconian plans. This would have invigorated the trade union movement, but also shown in practice the power of workers united in struggle.

Moreover, such struggle can have a transformative effect in breaking down barriers. When the Harland & Wolff shipyard workers occupied their yard in 2019 the mainstream press repeatedly commented on the significance of the main union organiser being from the South, given the history of the shipyards. For the workers themselves, it was without question that Susan Fitzgerald, who is a member of the Socialist Party, was their most effective representative.

Twenty years ago school students here participated in the global mass anti-war movement against the invasion of Iraq. This movement questioned the brutality of a system that leads to war and destruction, and brought young people – mostly educated separately – together in a common movement. The more recent climate strikes also reflected this, with thousands participating at the high point of 2019. Similarly, mobilisations for LGBTQ rights and against gender-based violence have shown the common experience and basis for struggle of working-class people, both Protestant and Catholic.

History has shown that the ruling elite will not hesitate to use sectarianism to cut across and disorientate any movement of the working-class and oppressed. Thus, it is also of vital importance that these struggles take conscious steps to challenge sectarianism and division. This must be a consistent, determined part of the urgent struggle for socialist change, in a movement that can unite all the exploited and oppressed against capitalism.

Notes

1. NI Life & Times Survey, 2022, www.ark.ac.uk

2. Dr Jacqui Montgomery-Devlin, Nov 2022, Briefing Paper No. 2, ‘The influence of paramilitarism in Northern Ireland on the recognition of child sexual exploitation in young males’

3. Allan Preston, 1 Dec 2022, Suicide figures for Northern Ireland reveal 237 deaths in 2021’, www.irishnews.com

4. Quoted in ‘Lord Randolph Churchill and Home Rule’, published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 July 2016

5. Socialist Party Statement, 23 Nov 2018, ‘Brexit and the Irish Border: A Warning to the Workers’ Movement’, www.socialistpartyni.org

6. Brandon Lewis, 22 Feb 2023, ‘The Good Friday Agreement must evolve to bring effective government’, www.brandonlewis.co

7. Reginald Maudling, UK home secretary, on 15 December 1971, www.oxfordreference.com