Reviewed by Finn McKenna

(spoiler warning)

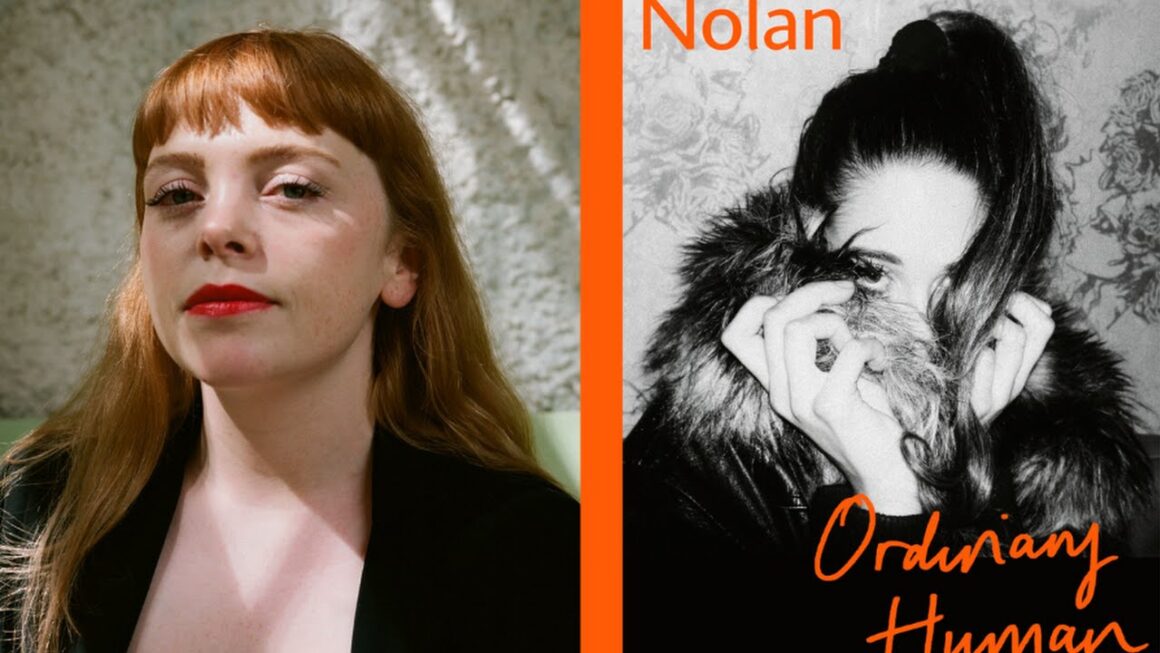

Ordinary Human Failings, the second novel by Irish author Megan Nolan, is a story that delves into the complex, at-times tragic, at-times remarkable, always-riveting journey of the Green family: fictional Irish immigrants coping and trying their best in whatever way that they can manage their lot in England in the early 1990s, following a series of life-rupturing events.

There is a slight disconnect between the title of the book and what the author has managed to achieve, as there is something extraordinary about what she reveals about the world with her writing. The book is anything but ordinary.

The title is a recurring motif – its three words point towards essential constituent parts of the book. Though it deals with many other themes, such as politics, the position of Irish people in Britain at the time, the oppressiveness of the Irish state – it is all the while mindful that this is a story about one ordinary family and the extraordinary circumstances that elevate them into the public realm and spotlight.

Mental Illness

Ordinary Human Failings marks a departure from Nolan’s first book, the acclaimed Acts Of Desperation – a story of the self-destructive journey of a young woman hostage to dependency within a toxic, abusive relationship. Yet there is a continuity between the two books insofar as both deal with the social position of women and mental illness. Both books are clearly influenced by the ideas of RD Laing, particularly Laing’s ‘Divided-Self’ – which itself is an attempt at synthesizing the Hegelian dialectical method and existentialism to explain people’s descent into mental illness; namely schizophrenic splitting.

In Acts Of Desperation, Nolan’s protagonist describes the psychological rupture involved in splitting, rooted in the downward spiral of toxic romantic attachment. Similarly, in Ordinary Human Failings we gain a deep insight into this process when the leading female protagonist, Carmel, is confronted with an unwanted pregnancy. Both accounts are enriching to any reader struggling to understand processes of downward spirals and splitting, and many readers who have experienced similar processes will be able to relate to the mental strain that Carmel experiences. The following excerpt demonstrates the continuity of Nolan’s ability to get to grips with the divided rupturing of the human psyche under immense strain.

“He listened to the way that her mind has split neatly in two between what actually was, and what she was capable of tolerating, and how the false part had taken over and dominated the over for months.”

Alcoholism

Alcoholism is another important theme in the book, particularly in relation to Richie. The alcoholism of Richie is examined in intimate detail; at the root of his condition is a profound loneliness and an ennui which he believed he would suffer throughout life, addict or not.

“The drinking, the not-drinking, would change nothing of this despair which was a part of him and always would be.”

These lines speak to a spiritual malaise and alienation that defined Richie to his very core. Nolan points towards why he may have suffered in this way when describing his tendencies towards inertia with all its crippling indecision. There is an account delivered by the author as to why Richie drank so intensely;

“Richie loved what he drank and came alive with it, was bestowed with great reserves of life and energy. He shed the usual nervy, downtrodden aura, the avoidance of eye contact, and seemed free and open, musical and eloquent.”

His alcoholism would ultimately define his ‘ordinary human failing’; getting into such a drunken state of irresponsibility that would result in losing his job in a restaurant in his early-20s. Many people would look at such an event and deem it insignificant, but for Richie it would further reinforce a sense of misdirection and purposelessness in his life.

What Ordinary Human Failings achieved with Richie’s character arc is an illustration of the processes that drove Richie towards alcoholism. Of course, it must be recognised that there are other material reasons as to why a character such as Richie was not able to surmount his existential despair; the general lack of opportunity in a bleak Irish society from which people emigrated searching for work in their hundreds of thousands, combined with lack of familial and state support to deal with mental illness.

Anyone with direct experience with life in Ireland at this time would be aware of the level of both state neglect and domination. Another detail worth noting is the fact that Richie and Carmel’s father, John Green, was the son of a woman born into a poorhouse. The dynamics, realities and struggles of working-class life are constantly present.

Out of the frying pan and into the fire

A defining event for the family was Carmel dealing with an unwanted pregnancy. This is one of the most distressing sections of the story to read. It demonstrates the reality of the position of women in society in the 1970s and the constant fear that clouded the lives of Irish women.

The sequence of events that brought Carmel and her family to London was rooted in the reality of the risk of incarceration of Carmel and stigmatisation of the entire family should they have remained in Ireland after Carmel’s pregnancy. Needless to say, the backward views this reflected were conditioned by the oppressive social control of the Church and State nexus at that stage.

Consequently, after she gives birth, Carmel’s ability to connect with her daughter Lucy is understandably stifled since the pregnancy was unwanted. The burden to raise Lucy falls to Carmel’s mother Rose until her untimely death. This creates a vacuum in terms of responsibility for raising Lucy. The disconnect between Carmel and Lucy is ultimately surmounted through the brave efforts of Carmel as she is confronted with what Lucy has done later on in the story.

The tale is centred around events whereby a small child named Mia died tragically in the housing estate where the Greens resided. The ghoulish, hawkish, poshboy-aspiring tabloid journalist Tom Hargreaves circles the Greens intent on exploiting the tragedy. Questioning his intentions early on, Carmel challenges Tom;

“Is it true, Carmel asked him. You wouldn’t describe us as knackers, or gypsies? Or thieves and liars? Or even just Paddies?”

Elsewhere in the book, Richie recounts getting flak from anti-Irish bigots in England on account of the Troubles. The politics of the day penetrates the lives of the Greens, as they themselves are the subject of discrimination in their everyday lives. Furthermore, they are also the object of manipulative desire for the despicable Tom Hargreaves, who is happy to whip-up fear and hatred against this Irish family for his own self-serving, tabloid-selling ends. Hargreaves is sociopathic, self-obsessed, ruthless, the epitome of dog-eat-dog, and extremely insecure and ultimately pathetic. Nolan’s development of this antagonist has been correctly noted by various reviewers as extremely impressive due to its multifaceted nature.

A humanistic tale

In the way that she writes her characters (specifically the Greens), it is clear that the author loves them and treats them without judgement – her method is one which lays bare why people behave in the ways that they do. For example, the tragic death of Mia itself is obviously a key underpinning event to the book, but it is not the sole one. The book is full of contingencies and accidents; full of decisions where characters did not realise the permanency of their consequences. The final few pages are woven into a full and elevated conclusion which shows the elasticity and strength of both Carmel and Lucy.

The book is defined by the fighting spirit of at least a section of its characters – Carmel especially is characterised by a sense of overcoming adversity, and an ability to move forward in life against tremendous odds. To be marked and scarred by one’s own history, yet still moving on with bravery and determination; the following lines stood out to the reviewer as definitive in capturing Carmel’s resilient outlook when it comes to facing life’s tests:

“She felt something like fondness or a grudging admiration, not towards her daughter but towards life itself, how persistent and absurd and reckless a force it could be.”

Another profound excerpt which brought the reviewer to a pause was the interaction between Lucy and her counsellor Diane;

“I think differently about you every time I learn something new about you, Diane said, but that doesn’t mean that I think worse of you.”

This reassurance from Diane is marked by a deep humanistic outlook; one that sees people’s capacity to change, to grow, to evolve – as what is being described here is the counsellor’s own changing perception as life progresses. On the theme of growth by leaps and bounds, Nolan also interestingly details how John Green’s character developed in a way that was conditioned by the tragedy that occurred in England;

“Her father had been pushed toward change only by the extreme pressure of crisis.”

Granted, there is also recognition of a tendency within the father to slide back to long-established norms and behaviours. With that said, Nolan’s talent to describe radical changes within family structures and dynamics themselves is something that’s remarkably enthralling – it also speaks as though it is a description of a revolutionary process.To finish this review, the reviewer couldn’t help but recall Marx’s favourite maxim: “Nihil humani a me alienum puto” – “Nothing human is alien to me.” Megan Nolan is a writer to be cherished, and her second book is a must read. For it is gripping, at times emotionally taxing and punching, while also exhilarating and inspiring – a celebration of love, struggle and endurance in the face of life’s slings and arrows of absurd and reckless fortune. It is worthy of the greatest accolade that one could perhaps praise it with; human.