By Donal Devlin

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

– Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley

“No one can overthrow me. I have the support of 700,000 troops, most of the people and all of the workers.” – Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran, June 1978

History is rarely kind to the bombastic hubris of murderous dictators; within months of the Shah’s above assertion, he was unceremoniously forced into exile on 16 January 1979. Beginning with street protests in the Autumn of 1978 and quickly evolving into mass strikes, a revolutionary movement of the working class and poor brought an end to his hated dictatorship.

A murderous regime

The Shah was initially brought to power in 1941 by British imperialism, later he became Iran’s absolute ruler after a coup in 1953 toppled the government of Prime Minister and radical nationalist Mohammad Mosaddegh. This was orchestrated by both the CIA and MI5, the U.S. and Britain’s intelligence agencies, after Mosaddegh had nationalised the country’s oil reserves. Democratic niceties were dispensed with in the interests of private profit.

The Shah’s Iran, alongside Israel and Saudi Arabia, became a crucial ally of US imperialism in the Middle East. It was the location for the CIA’s headquarters in the region, and by the time of the revolution, the US had 24,000 “military advisors” in the country. It helped establish SAVAK, the regime’s notorious secret police, that acted as an omnipresent hit squad that tortured and murdered tens of thousands of political prisoners.

The Shah also built a colossal military apparatus that by the time of the 1970s became the largest importer of military weapons in the world. Between 1971 and 1976 alone it purchased $8 billion in weaponry from the U.S.

Extreme inequality

Ruthless repression was combined with attempts to rapidly industrialise the country, what the Shah called his “White Revolution”, believing he could modernise Iran to become an advanced capitalist state.

The Shah and his cronies lived a lavish lifestyle on the backs of Iran’s economic successes. In 1967 he gave himself the title of ‘King of Kings’ (an unintentional nod to Shelly’s Ozymandius) and four years later he hosted a three-day global ceremony costing $22 million to celebrate his rule. A special location for the festivities was built on the site of Persepolis, the ancient capital of Persia, with a variety of the world’s capitalist and Stalinist leaders in attendance. At a time when 44% of Iranians lived below the subsidence poverty line, 18 tons of the finest food, including 30kg of caviar, were flown in from Paris. Such an obscene display of opulence only fuelled the resentment of the Iranian masses towards the Shah.

Revolutionary uprising

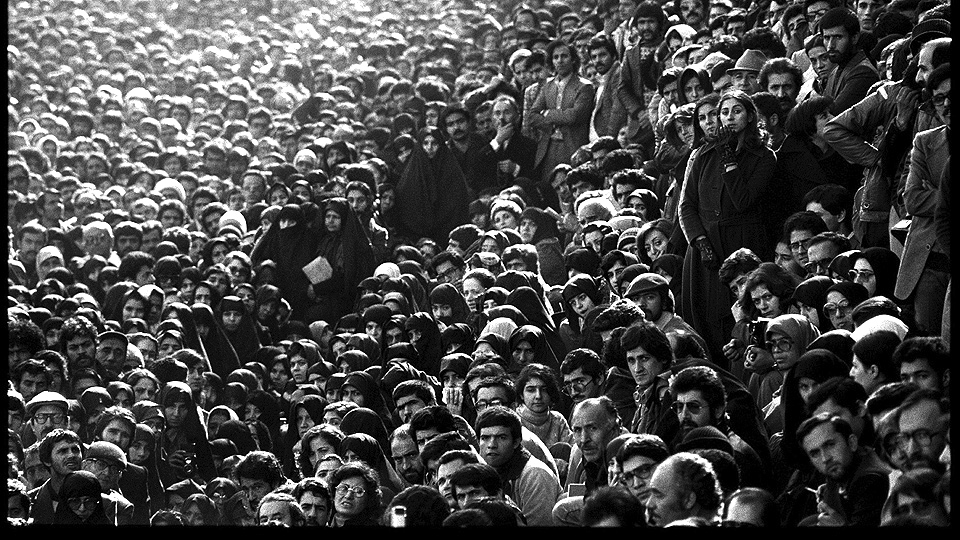

Extreme inequality, rapid industrialisation, state repression, oppression of national and ethnic minorities, and, after 1975, economic crisis, all became the combustible material for a revolutionary explosion. That’s exactly what happened on 7 September 1978. After a year of growing protests, two million took to the streets of Tehran. The Shah responded with the imposition of martial law and 2,000 were massacred on the streets.

This repression only propelled the revolutionary process. A major strike movement developed with the key sections of Iran’s working class moving into action. Oil, coal and transport workers all struck, with the latter refusing to allow police and army to travel on the trains.

Workplaces were occupied and democratically elected strike committees took over their running. As the movement mushroomed, rank-and-file soldiers began to mutiny and came over to the side of the masses. Peasants began to seize land and evict their landlords.

A force that had authority in the revolution were the Shia clerics and their leader Ayatollah Khomeini, who had come into opposition to the Shah’s rule in the early 1960s. Their populist message against inequality allowed them to build a base amongst Iran’s poor.

The failure of the left

However, this was far from being an uncontested influence on and leadership of the revolutionary events of 1979. The Tudeh (the Iranian Communist Party) and other forces on the left also had a significant base of support in key workplaces and shoras (democratically elected workers’ councils that emerged in the period following the toppling of the Shah). They constituted a real basis for the establishment of a democratic socialist state in Iran. The policies of the Khomeini, notably the mandatory wearing of the hijab, were met with mass opposition. On International Women’s Day 1979, hundreds of thousands of women took to the streets for six consecutive days to protest this measure.

The aforementioned left forces largely tail-ended Khomeini, however, despite his pro-capitalist, reactionary policies and opposition to the shoras. In doing so, they squandered an opportunity for socialist change and allowed counter-revolution to triumph. By 1981, the Tudeh and the organised left and workers’ movement were suppressed and many of its activists imprisoned.

A critical lesson of this period is the need for a revolutionary socialist alternative that stands against imperialist and monarchist rule, as well as the theocratic rule of the existing regime in Iran – another variant of capitalism that likewise stands for a system of exploitation and national and gender oppression.