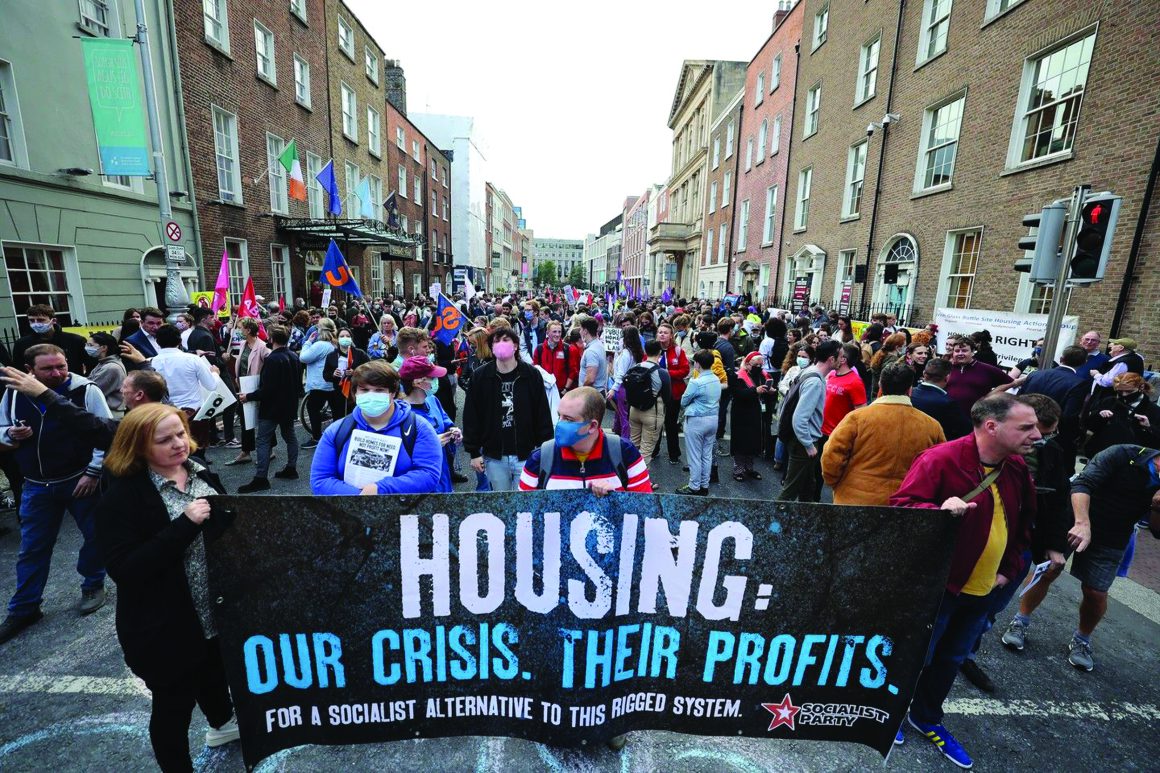

By Leah Whelan

The housing crisis is not unique to Ireland; it is a global issue impacting working-class and poor people. It is currently estimated that 1.6 billion people are living without adequate shelter, and that one in seven people live in slums – with this due to rise to one in four by 2030.1

As people struggle to find secure and affordable accommodation in some of the major capitalist cities, financial landlords – more commonly known as vulture funds – continue to monopolise the housing market for profit. The global real estate market increased its size in 2020, growing faster than the previous year, with a massive $10.5 trillion invested between 2020-2021.2 While working-class people faced financial struggles through loss of jobs, hours and pay due to the Covid crisis, financial landlords took advantage of the crisis and made a killing.

Ireland saw house price inflation jump to 8.6% in 2021 – the fastest level of growth seen in the market in almost three years. In 2020, €1.3 billion was invested into “income producing real estate”.3 At the same time, ordinary people struggling to pay mortgage and rent debts were still being served eviction notices,4 despite the government’s temporary ban on evictions.

While capitalism continues to view housing as a commodity rather than a human need, the global trend of workers losing out will only worsen. With more cities becoming unaffordable, people will be forced into untenable housing situations, contributing to job precarity, mental and physical health problems and poverty.

A permanent crisis

The housing and homlessness crisis in Ireland has been headline news for over five years now and still it worsens as governments rely overwhelmingly on the private market to deliver housing. The current housing problem emerged from the Celtic Tiger, during which the average house price rose from €67,000 in 1991 to €331,000 by 2007, fuelled by speculation by banks and developers. The bubble burst with the 2008 financial crash. Developers, many saddled with ‘ghost estates’, stopped building. The state likewise withdrew from any form of house building for up to eight years.

The recession created cheap assets and a space for those with capital to step in. Government parties gave the green light to financial landlords – with finance minister Michael Noonan infamously uttering, “vulture funds carry out a really good service”. These vulture funds, which viewed the economic prospects in Ireland as more favourable than southern Europe, have bought up land and thousands of housing units in Ireland.5

This is indicative of significant changes around the political economy of housing over the last decades, with more people now having to use the private rental sector (PRS), whether of their own accord or through government-funded housing schemes (such as HAP, which is the epitome of governments’ reliance on the private housing market. The PRS generally is regarded as the leading cause of homelessness in Ireland according to Focus Ireland.

Prior to this overreliance on the private market, indeed since the founding of the state and through the 1970s, the state played a direct role in providing large numbers of affordable homes through low-cost mortgage lending, and the construction of social housing.6 Council housing initiatives, such as the communities of Crumlin, Drimnagh and Ballyfermot in Dublin provided new generations with alternatives to tenements.7 Council house building reached nearly 9,000 per year, in the 1980s it was over 5,000 per year.8 During this time, the PRS decreased from 25% to 10% of all homes (Buckley, 2019).

International examples also show successful public housing roll-outs, notably in places like “Red” Vienna in the 1920s, where a powerful workers’ movement brought about a mass programme of house building by the state.

Privatising housing provision

However, social housing was deliberately undermined through the promotion of the idea of ‘homeownership’, and a ‘home-owning democracy’ in the 1980s.9 Capitalist figures created a sense of individualism around homeownership, promoted alongside the ideals of the family. Leading this charge Margaret Thatcher famously announced: “there is no such thing as a society. There are individual men, and women, and their families”.

Capitalist governments all over Europe adopted similar policies of encouraging home ownership. To do this, the state began to sell off state assets – transferring social housing from local authorities (LA) to former tenants and private landlords, reducing the influence of LAs, and inevitably increasing the power of those with capital.

In 2008, the decrease of social housing was clear with only 600 units built, and by 2015 only 75 social housing units were built.10 Incentives were given to council tenants to buy their homes. Of course we don’t criticise working-class people for availing of this, however we do criticise the governments which failed to replace the social homes that were now privatised. This housing model began the trajectory of increased privatisation and chronic unaffordability.

Enter the vulture funds

Financialisation of the housing system is evident from the significant changes to the housing market over time. After the financial crash, mortgages were transferred into commodities which were then sold on the international market. Vulture funds were able to purchase large bundles of mortgages at a discounted rate of 70% from Irish financial institutions.11 Through this process, vulture landlords have increased their holding of the total Irish mortgage stock.12 The result is that working-class and young people are less able to access housing in Ireland.

Financial landlords play a bigger role than just buying up and renting out large swathes of housing units. They also keep many of them empty, which helps to keep rent prices artificially high. Currently, hundreds of luxury apartments in Dublin lie vacant. The Business Post published a report from the Residential Tenancies Board (RTB) that shows nearly four-fifths of the 246 apartments in phase three of Clancy Quay are empty.13 The article also disclosed that nearly half of the 190 apartments in Capital Dock are vacant. Both units are owned by American real estate agency Kennedy Wilson which has over 2,000 rental units in Ireland.14

As a result of rents being kept artificially high, and homes purposefully empty, bidding wars have begun on properties that do go on the market. Such bidding wars have further locked out even those financially stable enough to gain mortgage approval. For example, a house in Dublin recently went on sale with an asking price of €685,000, but quickly attracted bids of over €1.2 million – nearly €500,000 over the asking price.15 House prices are estimated to rise by 12% by the end of year.

Also in the post-Crash period, banks ditched the initiative to provide loans and instead introduced a period of credit crunch that made it more difficult to access a mortgage. In short, the private market continues to dominate, create competition among buyers, poverty among renters and fuels the ever-increasing housing crisis.

Useless government schemes

Governments have introduced many schemes over the years to try and curb the increasing threat of mass homelessness. However, the schemes are routinely inadequate. The ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ scheme implemented in 2016 by the Fine Gael government failed to grasp the severity of the housing crisis. The scheme inflated statistics by including homes that were not exclusively new builds in their figures. The failure of the scheme was evident in the record number of 10,000 homeless people in 2019, which was 65% higher than when the scheme was first introduced.16

While the ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ scheme was criticised for not correctly analysing the housing crisis, the new ‘Housing For All’ programme introduced in September 2021 is even further off the mark. The government is peddling the typical narrative that this plan will finally solve the crisis. However, the plan is nothing more than a capitulation to developers and lobbyists.

Researcher Rory Hearne highlights that the plans are a maintenance of the status quo and a continuation of generation rent.17 The cost-rental scheme will only be offered to 5% of current rents. His report also shows that only 2% of the current 450,000 young adults living at home will be housed under the scheme; however, the scheme has also failed to account for the future growth of the population. The plan’s deficiency is also seen in its reliance on meaningless figures for private sector developments.18

Multifaceted problem

Decades of landlord and developer-led policies mean that young and working-class people will continue to suffer. In Ireland, almost one third of 18-39 year-olds are renting privately. The lack of building and access to social housing impacts single parents and their children disproportionately, particularly single mothers.19 Financial and tenure insecurities also have a severe effect on the emotional and social well-being of tenants. This is evident from the 60% rise in 2020 of deaths in homeless hubs, B&Bs, and direct provision centres, and on the streets.20

A major issue emerging in Ireland at the moment is the student accommodation crisis. Students are forced to drop out of college due to the lack of accommodation. In addition, some students are traveling anywhere from three to five hours per day to attend classes; others are staying in hotels and B&Bs to complete their education.21 The president of the Union of Students in Ireland called on the government to declare the student accommodation crisis as an emergency, and to provide long-term and sustainable solutions for students.22 Students have organised protests and a sleep-out outside the Dáil to highlight the growing issue facing students all around the country.

Increasingly, the housing crisis is merging with the climate crisis. In different parts of the world — especially coastal towns and cities — climate change will be a factor in forcing people to move, or even emigrate, compounding the refugee crisis. Extreme weather events will be another factor to contend with. In September 2021, New York was hit with severe flash flooding that left many people homeless. Forty five people died, most of whom lived in basements advertised by landlords as alternative forms of “affordable” accommodation for poor and immigrant families, often cramped and windowless.23

This further highlights not only that the housing and climate crises are highly interlinked, it shows that both are class issues. Workers and their families bear the brunt. Wealthier areas are protected with better infrastructure, and those with capital can take extra precautions in protecting themselves.

What we need

Housing is a basic necessity and human right, and just like health, education, transport and other vital public services, it should not be commodified so that a cabal of developers, bankers, vulture funds and landlords can profit from people’s wants. It is illustrative of the deeply parasitic nature of capitalism today that this right is denied, and this denial means we live in a world where slums still proliferate throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America. In the wealthiest countries, too, many are condemned to homelessness or no security of tenure.

The housing crisis is a clear refutation of the free market ideology that insists that the “hidden hand” of the market will deliver for the majority in society. Clearly, the supply of affordable housing does not match the demand that’s there for it.

The wealth and resources exist to provide everyone on our planet with a quality, eco-friendly home as part of a fully-resourced community. This is a minimum we should expect in the 21st century. As long as this wealth is in the hands of a super-rich minority, however, this potential will not come to pass. A socialist programme for housing begins with the understanding that the rules of their capitalist system must be ripped up if the needs of the majority are to be met.

Rents must be slashed and frozen to levels that are affordable, and economic evictions banned. The assets of the various vulture and cuckoo funds must be seized, and their practice of speculating on housing outlawed. Similarly, the free land and vacant properties of developers and landlords must be taken over and used productively. For instance, the Catholic Church has land assets estimated at €3.7 billion from 18 congregations.

Commencing a major programme to construct public homes to rent or buy is necessary, but generally, social housing must be made universally available to all working-class people, regardless of income. The major construction companies, such as Cement Roadstone Holdings (CRH), must be brought into democratic public ownership so homes can be built at cost price. This could be matched with building the necessary infrastructure, e.g. schools and childcare facilities, to provide a decent quality of life, including massively expanding the public transport system.

Recently, a referendum in Berlin against the backdrop of rising rents, saw a majority vote to expropriate the assets of corporate landlords. This example has been rejected by parties such as Sinn Féin, but it points to a crucial way forward for here. It also showed the potential to build a movement to take on the profiteers and win real, tangible victories.

A movement for housing justice must also be linked to the need for broader anti-capitalist and socialist change. This means taking the key levers of the economy into public ownership, under the democratic control of the working class, and organising society to provide everyone with the home they need, while safeguarding our environment.

Notes

1. Habitat For Humanity, ‘What is a slum: Definition of a global housing crisis’, Habitatforhumanity.org.uk

2. Hariharan G G, Rishikesh Patkar, Razia Neshat, ‘Real Estate Market Size 2020’, www.msci.com

3. John Ring, 23 Feb 2021, ‘2020 Sees Big Finish to Property Investment Market as Seasoned International Investors Commit’, www.savills.ie

4. Aoife Moore, 16 June 2021, ‘1,100 households given eviction notices despite ban on people losing their homes’, Irish Examiner, www.irishexaminer.com

5. Financial Times, 9 May 2012, ‘Vulture funds circle over Ireland and Spain”, www.ft.com

6. Rory Hearne, 2017, “A home or a wealth generator? Inequality, financialisation and the Irish housing crisis”, www.tasc.ie

7. Mick Barry, 2018, Housing and Capitalism: Our Crisis.Their Profits., Socialist Party Publication

8. Ibid

9. D. Andrews & AC. Sánchez, “The Evolution of Homeownership Rates in Selected OECD Countries: Demographic and Public Policy Influences”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol.2011/1

10. Dan McGuill, 6 May 2016, ‘Only 75 local authority houses were built in 2015 – the worst year on record’, www.thejournal.ie

11. Rory Hearne, 2017, “A home or a wealth generator? Inequality, financialisation and the Irish housing crisis”, www.tasc.ie

12. Ibid

13. K. Woods & S. Taaffe-Maguire, 17 January 2021, ‘Hundreds of luxury apartments controlled by US fund lie vacant in capital’, Business Post, www.businesspost.ie

14. Ibid

15. RTE News, 29 June 2021, “What’s driving bidding wars for houses in Ireland?”, www.rte.ie

16. Peter McVerry, 19 July 2019, ‘Rebuilding Ireland is an abject failure’, The Irish Times, www.irishtimes.com

17. Rory Hearne, 25 Sept 2021, ‘It’s simple – the Government favours landlords and investors over renters’, www.thejournal.ie

18. Paul Hosford, 3 Sept 2021, ‘Housing for All reliance on firms criticised’, Irish Examiner, www.irishexaminer.com

19. Emily Scurrah, 7 Mar 2019, ‘International Women’s Day 2019: Women and The Housing Crisis’, www.neweconomics.org

20. 2 June 2021, ‘Dublin homeless deaths increased by 60% last year – report’, The Irish Times, www.irishtimes.com

21. Rónan Duffy, 23 Sept 2021, ‘We’re outraged, we’re frustrated: Students to sleep outside Dáil to highlight accommodation crisis’, www.thejournal.ie l

22. Ibid

23. RTÉ News, 4 Sept 2021, “Deadly floods expose dangers of New York’s basements”, www.rte.ie