By Kevin Henry

After two years of boycott by the DUP, Stormont has now been restored with the election of Speaker, First and Deputy First Minister and of a four-party Executive, involving every party entitled to join the Executive on the basis of d’Hondt. The fact that it will have the first non-unionist First Minister is of significant symbolic importance for many, particularly Catholics, including those who have never voted Sinn Féin – even if the position has no real power as it is a joint office with the Deputy First Minister,.

Traditionally the largest party usually takes either the finance or economy portfolio, and the second largest party would take the other. However, this time when Sinn Féin chose economy, the DUP chose education not finance, leaving Sinn Fein to request a recess to discuss whether they should take it, which it ultimately did. Thus Sinn Féin holds the most important ministerial positions for allocating funds. For the DUP, as well as wanting education in order to take initiatives to curtail Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE), it reflects a more “hands off” approach to government in an attempt at placing more of the burden on Sinn Féin about deciding cuts.

In general, the restoration of this Executive has been met with far less fanfare than we have seen previously with, for example, ‘Fresh Start’ or ‘New Decade, New Approach’. In part, this reflects the fact that people feel they have been here before, and unlike previous deals this was not a deal between political parties but primarily one between the DUP and the British government. It also reflects a reality that while most people want a return of Stormont, there is a strong sense that significant sectarian polarisation remains, particularly with the divisions among the DUP / Unionism. It also reflects a recognition that despite the extra £3.3 billion in funding from Westminster, it is at best a temporary fix and we face serious economic difficulties if we play by Westminster’s rules.

Why deal now?

The strike of 18 January, which involved 170,000 workers across the public sector, including health, education, civil servants and transport, played a hugely important role in putting pressure on the DUP. On the day, Socialist Party members distributed thousands of leaflets calling for ICTU to name the next day of all-out action, i.e. broadening the action to involve the private sector. We also called for money from Westminster to be released, whether Stormont was restored or not, and not be held ransom. The strike most certainly acted to put pressure on the more moderate wing of the DUP, who in any case generally felt that the boycott was running its course and that if they got some movement on the Protocol they would have the basis to return to Stormont.

However, this wasn’t the only factor that led to a deal. When Jeffrey Donaldson collapsed the Executive two years ago, Boris Johnson was Prime Minister and he was publicly considering the idea of breaking with the Protocol, even if it meant provoking a trade war with the EU. Johnson represented the faction in the Tories that wanted to use Brexit to aggressively reposition Britain’s position in the world, based on the utopian idea of reversing the trend that has reduced Britain from the largest empire in the world to a third-rate global power, effectively a lapdog for US imperialism. The new Cold War, turbocharged by the war in Ukraine, has seen significant hardening of the American and European imperialist bloc on one hand, and Russian and Chinese imperialist bloc on the other, with increased militarisation. Sunak as Prime Minister has dropped many of Johnson’s utopian plans in favour closer alignment with the EU and US.

It is also likely that the Tories will lose the General Election later this year and be replaced by Starmer’s Labour Party, who likewise will not favour significant regulatory divergence from the EU. As others have pointed out the current deal in reality has elements of “soft Brexit,” or Teresa May’s backstop. The hardline Brexiteer wing of the Tories, to which the DUP is closest, has been significantly knocked back.

Unionism split

Opinion polls show that three quarters of DUP voters back the current deal. Not that this meant the moderates had an easy road to restoring Stormont. They faced significant opposition, both internally (among their officers and executive) and externally from Jamie Bryson and the TUV who distributed hundreds of posters saying “Stop the DUP Sell Out”. Groups like ‘Let’s Talk Loyalism’ organised thousands to sign ‘Keep Your Word’ pledges. While these events have not been massive they do reflect real discontent among a section of Unionists about the institutions being restored, which is unlikely to simply go away.

If the moderates are seen to not be delivering for their community, if their support was again to slump consistently in opinion polls, it would likely trigger a leadership contest. The recent opinion poll that showed them losing support to TUV is illustrative of that concern. But there are opposing pressures – the DUP remains the only Unionist party capable of challenging Sinn Féin as the largest party in the North.

No to stormont as normal

A major issue for the new Executive is the question of long-term funding. The £3.3 billion from Westminster is only for the next year, and even then it is not enough to actually provide inflation busting-pay rises. At most what is on offer is ‘pay parity’ with workers in England. The trade union leadership, especially those close to Sinn Féin, will push to limit further strike action so that Stormont can get on with business as normal. Ordinary workers should reject that approach and organise to be prepared to take action. The fact that junior doctors plan strike action in March shows that demands on wages are not going away.

Some of the money on offer is also tied to Stormont implementing £113 million in revenue raising measures. Michelle O’Neil has ruled out water charges and hikes in regional rates, but not yet other regressive measures, such as hiking tuition fees, cutting free transport to over 65s etc. Correctly, the parties have pointed the finger at Westminster and called for more money. But the question arises what should they do if Westminster refuses to hand over more money. What they should do is set a ‘needs based budget’, and implement it even if that means breaking the law. The trade unions and community groups would get a massive response in mobilising people. Given their record of passing on Westminster cuts, however, it’s highly unlikely they would do that. But it’s necessary to raise such an approach to illustrate that there is an alternative to simply passing on cuts.

Northern Ireland has seen the highest rate of strike action since 1989, despite confusion among many workers about who they are striking against and how they can win. With the Assembly restored it will be clearer where the problem and the target lies. It’s also not just on the industrial plane that Stormont will feel pressure. A large number of issues, including gender-based violence or the crisis around Lough Neagh, will push people to demand action from the ministers who are meant to be responsible.

Alternative to Sectarianism needed

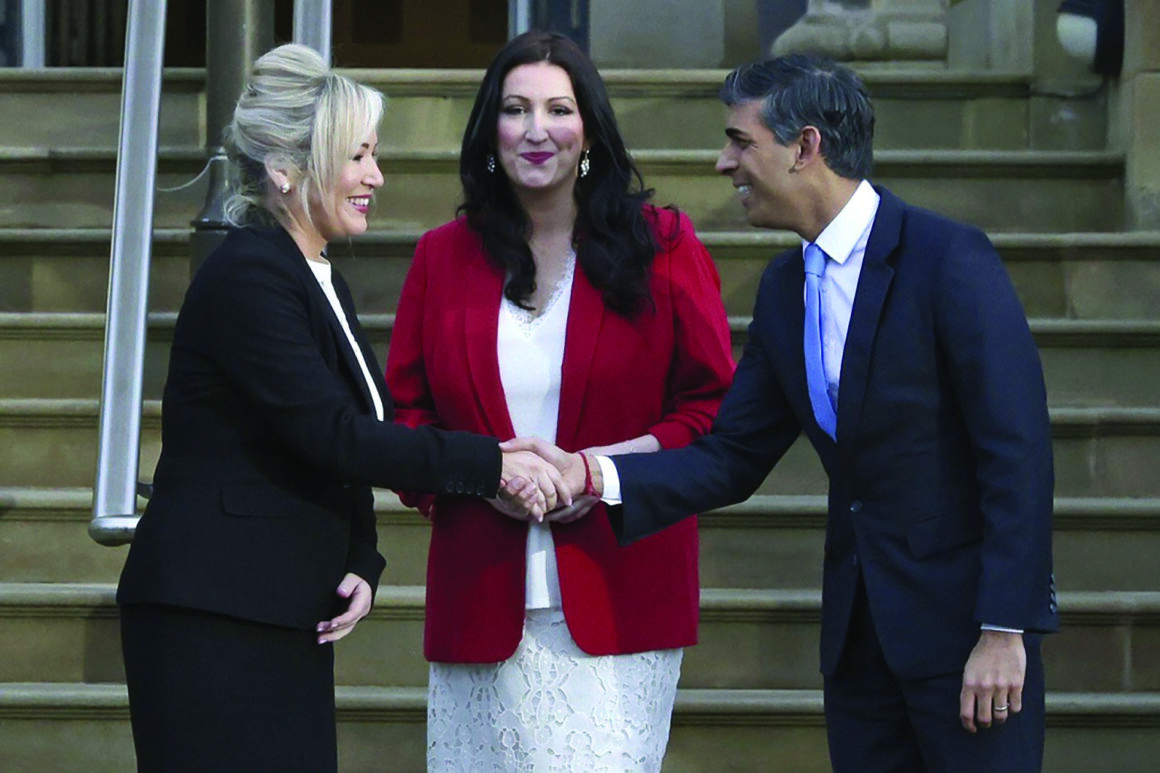

As has always been the case, the sectarian polarisation in society means that the Assembly is inherently unstable and this is increasingly the case as issues under debate are more and more the fundamental issues of division. Smaller issues won’t go away, either. For example, the approach of the new-Deputy First Minister, Emma Little-Pengelly, is illustrative of an approach that will ensure sectarianism is consciously injected into every situation. Funding for Casement park, which would allow UEFA games in 2028, is for Little-Pengelly tied to extra funding for other sports. Of course this is in keeping with Sinn Fein and the DUP’s long-established approach of engaging in sectarian carve ups on the issue, but rather than it being done quietly it is now being done in the public press.

The more fundamental issues can be seen in the Tory / DUP deal document, in which the preamble effectively rules out calling a border poll if conditions will not be ‘objectively met’. Yet there is no agreement on what the conditions are, and more importantly, an official government document points to an open break with the idea that Britain has no selfish interest in Ireland. At the same time, Mary Lou McDonald says a United Ireland is within touching distance. So you will have increased ‘preparation’ or agitation on part of republicans, but intransigent opposition to calling one on part of unionism and the British state. Socialists have to point out that a border poll is not a solution, but neither is its denial – only the building of socialist cross-community, working-class politics can resolve these issues.