This article by Saana Taussi explores the work of Zhenotdel, the women’s department of the central committee of the Russian Communist Party, and the lessons we can draw from their work in fighting oppression.

The Zhenotdel was founded by Bolshevik women, such as Alexandra Kollontai and Inessa Armand, in Russia after the 1917 revolution. The department was formed to ensure women’s full participation in Soviet Society. Despite the exceptional effort the Zhenotdel made in involving working-class and peasant women in social and political life, the department and its unique work are not common historical knowledge today.

Women’s Position Leading Up to the Revolution

As in countries all over the world, women were victims of oppression in pre-revolution Russia. The Bolsheviks – the revolutionary party which would seize control of the government in the October Revolution – referred to the specific burden that working-class women carried as suffering a double oppression in society. This refers to an oppression rooted in both capitalism and peasant patriarchy. Working-class women were constrained by class, but also by the ‘traditional family’, which limited women to the role of mothers and wives. The Russian Empire was semi-feudal, with a ruling class of landlords and a powerful church hierarchy. Constrained to specific roles, women had limited ways of seeking economic independence, and often no access to education or even the ability to read and write. These factors, alongside ingrained sexism in society, were huge barriers to women’s involvement in politics, not to mention other basic rights like access to abortion or divorce. Although the oppression of women was more pronounced in Tsarist Russia, it was not unlike the oppressive patriarchy we experience in the modern day, which still very much constrains the freedom of women and people generally. This has been especially evident in, for example, the recent attacks on our bodily autonomy such as the overturning of Roe V Wade in the United States, and in the rampant right-wing attacks against trans rights globally.

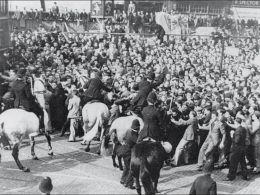

In the pre-revolution society, women who were in the workforce too were deeply unsatisfied, and in the years before had often been marginalized within trade unions. However, working women persisted in seeking collective solutions to their exploitation, and the number of women in the workforce starkly increased due to men being sent to fight in World War One. The 1917 February revolution itself was led by women’s initiative, as they took to the streets on International Women’s Day, with a strike declared in the majority of factories and plants, and some 900,000 workers joining striking women on the first day. This revolutionary spirit was not only among women workers but also those women who were queuing for bread and kerosene. In the summer after the February revolution, women were also a part of a large wave of strikes which included a wide range of service sector workers. Although the February Revolution ultimately fell short of what followed in October, the importance of women to the revolution was clear to the Bolsheviks, and they put firm effort into reaching the women who were fighting and radicalising. Existing women comrades for example established study circles for women strikers, to help them politicise their struggle.

There was an understanding among Bolsheviks that the liberation of women was essential to achieve a socialist society, as emphasized for example by Lenin and Engels for decades leading up to the revolution. For Marxists today this point is even clearer. The oppression of women has always been part of class-divided, unequal societies. The desire to keep property and political power within the family line means paranoid control over women’s bodies. Under capitalism, the unpaid, unrecognised labour of women in housekeeping, child-bearing and childcare plays a role in reproducing capitalism’s labour force, with this reproduction, tied in turn therefore to production – to profits for the capitalist class. Where the capitalist state fails to provide services, and the bosses fail to provide benefits, ‘the family’, ie women, are expected by society to pick up the slack. Today, unlike in Tsarist Russia, most women work – but still do far more than their share of housework and childcare, putting in a second shift after formally clocking out. In the workplace, women are concentrated in extremely important but underpaid sectors of the economy such as childcare, nursing, cleaning and textiles. Here, sexist stereotypes allow employers to get away with super-exploitation. These points are underlined by the inspiring role of women textile workers in the revolutionary events in Myanmar in 2021.

Not only is gender oppression ultimately rooted in the class-divided society against which we are fighting, but a blow struck for the rights of women is also a blow against the state and the ruling class. When socialists and the workers’ movement broaden out the struggle to encompass other movements for liberation, it proves to be, in the words of Clara Zetkin, ‘a pillar of strength.’ Strikes against sexual harassment and transphobia remind us that there is no barrier between different struggles against oppression and exploitation.

Likewise, women comrades were in leading roles within the Bolshevik party on both national and local levels. When the provisional government was overthrown in October 1917, women were there too to storm the Winter Palace.

Post-Revolution and the formation of the Zhenotdel

After the Bolsheviks succeeded in overthrowing the capitalism and landlordism of the Russian ruling class and the Tsarist regime in 1917, unprecedented ways for radical change opened in society, unlike anything we can see in the modern day. This led to some of the most important and basic rights for women being quickly implemented, such as religious marriage being abolished and easily accessible divorce legalized.

Soon after the revolution a civil war broke out, which meant society was still in turmoil and socialism was not on a secure footing. Although the male Bolsheviks were supportive of women’s liberation, to some of them women’s emancipation was now secondary to the economic and military challenges facing the state (Even though there were thousands of women literally fighting for the revolution, including as guerrilla leaders and machine-gunners). This is partly perhaps due to the material on women’s emancipation within the party being somewhat marginal before 1917, and Lenin himself criticized the male comrades’ lack of advanced development when it came to their understanding of women’s position.

However, comrades such as Kollontai, Armand and some other members of the leadership argued in turn that mobilizing women to defend the revolution was a central way of combatting the crises the new Soviet republic was facing. In order to do this, women needed to identify the revolution as a force of liberation, and many argued this needed to be incorporated into every area of party work. And precisely in order to make the revolution a liberatory force, the Zhenotdel was formed. In November 1918, Kollontai and Armand organised the first All-Russian Conference of Working Women, with over a thousand women attending. Their message was that women’s emancipation went hand in hand with the building of socialism.

New Initiatives and Women’s Emancipation

Because the nuclear family model often trapped women and equated them to property, the Zhenotdel launched a number of initiatives and projects to relieve women from the constraints of their homes. They organised the opening of canteens, laundries and nurseries, and organised schemes to recruit women into workplaces on an equal footing with men. They set up factory and workplace inspections to enforce compliance with laws protecting working women’s health and safety, and beyond the workplace, organised unemployed women and set up cooperatives. Employment laws were renewed to include paid maternity leave both before and after birth and access to nursing rooms in workplaces to allow breastfeeding. The Zhenotdel also managed to make abortion available in Soviet hospitals free of charge in 1920, as the first country ever to do so. This lasted until 1936 when Stalin banned it again.

Through bettering women’s ability to take part in the workforce, as well as in life outside the home, women’s emancipation could begin. The Zhenotdel sought to actively support women in taking action within their communities, for example through setting up delegate meetings to represent working-class women within their workplaces and communities, and ran internship programs to train women for new roles in factories and government departments. Women were elected to the delegate meetings from outside of the Communist Party, although many would end up becoming active members down the line.

The Zhenotdel in Soviet Central Asia

The Zhenotdel also launched the Communist Women’s International and did political work around Soviet Central Asia, to take their work further in aiding the participation of women in social and political life.

The Russian Revolution was not just Russian, but encompassed many nationalities oppressed by the Tsar. Central Asia had a very diverse population, including many communities utterly dominated by landlords and Muslim clergy. Uzbekistan was one of the countries where the Zhenotdel took their work. The community there was strongly divided according to traditional conceptions of gender roles, with women secluded, veiled, and not allowed to be in contact with men outside of immediate family. The Zhenotdel was imaginative and culturally sensitive in drawing women into social and economic participation through establishing women-only clubs and cooperatives, with childcare facilities, medical consultations, and cultural activities organised around them. The spaces being women-only allowed women to attend without conflict with husbands and other male family members. In a Kommunistka article Kollontai described these as “schools where women are drawn to the Soviet project through their own self-activity and begin to cultivate the spirit of communism within themselves” (as quoted in McShane, 2019).

In Uzbekistan, women’s participation in the economy was encouraged through setting up women-only shops, where women could sell their produce directly to other women rather than relying on the main cooperatives to help them. In these shops, there were childcare facilities, discussions, and literacy classes. The number of Uzbek women in producer-consumer cooperatives went from 225 in 1925 to 1,500 in the following year. Though relatively the numbers were not huge, it showed that there was potential to provide women with economic independence in a culturally sensitive way. Building women pathways into a work life was important, as they would gain more economic independence, and view themselves as equal members of society through their taking active part in it.

Clara Zetkin reported back from a Muslim women’s club in Tblisi, Georgia in 1924. The club proclaimed the full equality of women in all social fields, and the women within it were eager to participate in the transformation of society that had begun since the revolution. The club had been formed with forty members in 1923, and a year later it held over 200, rapidly increasing. Zetkin quotes one of the women speaking of the suffering and oppression they have endured under patriarchy, and how now there is hope for better: “now, my dear sisters, how everything has changed! The revolution arrived like a mighty thunderstorm. It has smashed injustice and slavery. It has brought justice and freedom to the poor and oppressed. Our father can no longer take us when we are young and force us upon the bed of a strange husband. We are able to select our husband and he must never again become our master; rather he shall be our friend and comrade. We want to work and to fight next to him and help to construct a new society” (Zetkin, 1984, p.161).

How socialism fights gender oppression

Soviet Central Asia also provides a rich example of how it is only with socialist change that we can begin to put an end to gender oppression. The Soviet Union represented an attempt to build socialism in an isolated and semi-feudal society, which was hijacked by a murderous and incompetent bureaucratic caste under the counter-revolution spearheaded by Stalin – under whose rule the peoples of Central Asia suffered many kinds of oppression and violence.

However, we can still trace many extraordinary gains for people generally and for women in particular. In a 1990 interview the BBC’s Central Asian Service spoke to an elderly teacher who had in her life availed of free infant healthcare, two years’ maternity leave with full salary, and a guaranteed childcare place for her children.

For this, she gave credit to the October Revolution: ‘I felt I was the luckiest girl in the whole world. My great-grandmother was like a slave, shut up her house. My mother was illiterate. She had thirteen children and looked old all her life. For me the past was dark and horrible, and whatever anyone says about the Soviet Union, that is how it was for me.’

(Dilip Hiro, Inside Central Asia, p 56)

What opened the way for these social gains? The importance of direct political intervention in the form of Zhenotdel is clear. But they were also a result of the overthrow of the landlords and clergy. An egalitarian planned economy with generous welfare opens up vast new avenues for women and other oppressed groups, including working-class and poor people generally. This by itself doesn’t end sexism or gender oppression. But firstly the experience of common struggle creates a deep bond of solidarity. Secondly, on the foundation of socialism, the struggle for the rights of women and the Queer community goes with, not against the grain of society, and makes rapid progress.

Hujum and the End of Zhenotdel

The political potential in working-class women even from the most secluded conditions was not that difficult to ignite, they merely needed to be given tools to carry out the process of their emancipation. In contrast to this incredible progress the Zhenotdel had made in the Soviet Union and in Central Asia, a culturally disruptive campaign called ‘Hujum’ was implemented in 1927.

Hujum was a campaign which claimed to enforce Muslim women’s emancipation by a forceful mass unveiling of women, which was put forward by those in the Soviet Union who had turned toward Stalinism. The First All Russian Muslim Women’s Congress had agreed that wearing the hijab should be non-compulsory, among other rights for women. However, this campaign was to force women to take off their hijabs, and the Zhenotdel was ordered to prioritize this, as it supposedly was about female empowerment. The Zhenotdel never prompted a mass unveiling, as they understood that such action would only provoke hostility toward their work from local communities and compromise the safe spaces they had created for women. And this is exactly what happened – as tens of thousands of forced unveilings took place, many Zhenotdel women and women taking part in their projects were physically attacked and even murdered. These women became martyrs for a cause that was supposedly for their liberation, while in reality they were deprived of the agency they had so recently achieved for themselves.

In the following years the Hujum was strongly condemned by the Zhenotdel and by other comrades. However, this was already the beginning of the end for the department.There was no room for Zhenotdel in the authoritarian regime of Stalinism, and by 1930 it was claimed that no separate women’s department was needed, and the Zhenotdel closed down.

Conclusion

“Even if we are conquered, we have done great things. We are

breaking the way, abolishing the old ideas.” – Alexandra Kollontai

Even though the Zhenotdel went down, along with the real attempts to achieve socialism that preceded Stalinism, there are many lessons to draw from its work. Some historians have described Zhenotdel as among the most ambitious attempts at emancipating women by a government. The Zhenotdel’s approach was actively and practically to change the material conditions within which women were living – through relieving them from their homes, through sharing childcare burdens, through discussions and literacy, and through economic participation. This allowed women to collectively seek solutions to societal issues, and to build their confidence – and ultimately, to dare to pursue a better life. Liberation is not something that can be imposed on people, through coercive schemes like de-veiling — and we see a pernicious version of it today in the French state’s vile Islamophobic policies. Liberation requires people to gain their own agency. That’s precisely why socialist feminism is and must be revolutionary — it’s about self-emancipation, the oppressed and exploited masses rising up, taking power into their own hands.

The case of the Zhenotdel also teaches us that oppression, whether of women, of the working class, of racialised people, or of the Queer community, needs to be deeply understood by us who are socialists trying to end all oppression. We need to take seriously the task of building a shared understanding of these issues, and through that building solidarity among all of us who are oppressed and exploited. Because in solidarity we can fight for lasting change, and for liberation for all. With genocide in Gaza, ecological breakdown, and anti-feminist and anti-trans backlash and the far-right threat, the need for a revolutionary socialist struggle and alternative is more pressing than ever. The revolutionary and inspiring lessons from the Zhenotdel must be absorbed and threaded through all our efforts in this regard.

References

Cox, J. (2017). The Women’s Revolution: Russia 1905–1917. Haymarket Books.

Engels, F. (1884). The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (4th ed). Pantianos Classics.

Hiro, Dilip. (2011) Inside Central Asia. Overlook Duckworth.

Lenin, V. (1977). On the emancipation of Women. Progress Publishers.

Marxist Internet Archive. (n.d.). Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East, Seventh Session September 7 1920. https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/baku/ch07.htm#women.

McShane, A. (2019). Women at the Heart of the Revolution. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2019/08/alexandra-kollontai-soviet-womens-rights-revolution-zhenotdel-uzbekistan

Taber, M. & Dyakonova, D. (Eds.). (2023). The Communist Women’s Movement, 1920-1922, Proceedings, Resolutions, and Reports. Brill.

Zetkin, C. (1984). Clara Zetkin Selected Writings. Foner, P., S. (Eds.). Haymarket Books.