By Manus Lenihan

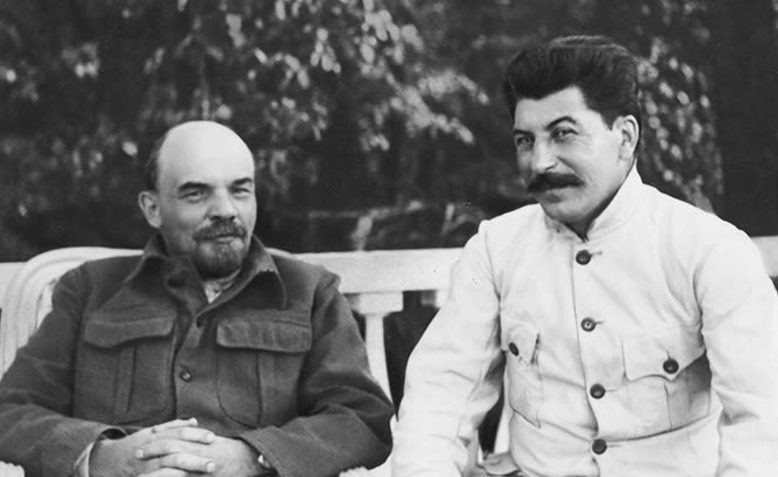

The Russian revolutionary leader Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known as Lenin, died on 21 January 1924 – 100 years ago today. The party he led, known as the Bolsheviks and later the Communist Party, led the working class to power in the October Revolution of 1917, the first successful socialist revolution in history. Until his death Lenin helped lead the newly-founded Soviet Union, along with the Communist International, which sought to spread the revolution internationally.

Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili, better known as Stalin, was the murderous leader of the Soviet Union from the late 1920s until his death in 1953. Lenin is associated with the dynamic revolutionary period, while Stalin’s name brings up images of one-party rule, paranoia, show trials and prison camps.

These were two fascinating historical figures, but when we ask the question ‘Did Lenin lead to Stalin?’, we are really asking whether the monstrous Stalinist regime was an inevitable outcome of the October Revolution.

A lot of people have strong views on this question. Some school books go so far as to trace the Stalinist system all the way back to a couple of lines in What Is To Be Done? – a booklet Lenin wrote in 1902 about how revolutionaries in Russia should best go about overthrowing the tsarist autocracy. Stalinists and anti-communist right-wingers do not agree on much, but both camps would argue that there was a fundamental continuity between Lenin and Stalin.

A more moderate, slightly more sophisticated version of the argument is that though Lenin was fundamentally different from Stalin, he set an inevitable course toward Stalinism with the October Revolution itself.

In this article we will answer both of these arguments.

Continuity or Rupture?

On paper, Lenin and Stalin presided over the same party and state. But things can undergo a complete change in content while keeping the same name. Institutions lag behind real life. The English kings William the Conqueror and the current King Charles have nothing in common apart from their titles. The Labour and Social Democratic parties today, which have thoroughly embraced capitalism, bear little resemblance to the same parties a few decades ago that represented workers and stood, at least on paper, for socialism. Likewise the Communist Party and the Soviet Union underwent a total change while keeping the same names and symbols. This is most blatantly evident with the Stalinist terror.

In October 1917 the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, at the urging of Lenin, overcame their final hesitations and began organising for the seizure of power and the socialist revolution. Stalin was a member of the Central Committee, but he played no prominent role either in the debate or in the uprising.1

The Stalinist Terror

Fast-forward 25 years, and we find that nearly all members of the Bolshevik Party Central Committee have died untimely deaths. A few died in the Civil War and the epidemics that accompanied it. Even fewer survived into the 1940s. But a large majority were executed or assassinated at the hands of Stalin. The foremost commanders of the Red Army during the Civil War went the same way: they were arrested on fabricated charges and massacred.

Nearly one million people were murdered in the worst period of Stalinist terror, 1936-1939. Many more were killed throughout Stalin’s time in power, and millions sent into the notorious Gulag – a system of forced labour camps. The foremost categories among the prisoners show what the Stalin regime was scared of. The Russian historian Vadim Rogovin recorded that 41,362 people were arrested as ‘Trotskyists’, i.e. left oppositionists, in 1937-8 – by far the most numerous political group among those arrested.2

If Lenin had lived, he would almost certainly have been persecuted by Stalin. There’s little reason to suppose that he would have been spared when all his closest comrades were murdered. So, rather than continuity between Lenin and Stalin, we see the most dramatic rupture imaginable.

Lenin debated opponents, Stalin shot them

Stalin’s violence also presents a contrast between how Stalin and Lenin treated their respective opponents. Both in the underground and in power the Bolsheviks and their allies went through many heated debates. Sometimes the destinies of hundreds of millions of people hung in the balance. But Lenin did not murder those who disagreed with him; he engaged in serious written and spoken debate.

Even when Kamenev and Zinoviev, two leading party members, exposed and condemned the plan to seize power in October – putting the whole revolution at risk – there was no question of a violent response (although Lenin did argue for their expulsion, and even that was a rare occurrence). Indeed, they remained leaders of the party. Even more dramatic debates raged around the Brest-Litovsk Treaty with German imperialism the following year.

One-party state vs Soviet democracy

Lenin envisaged a multi-party democracy within directly-elected workers’ councils or Soviets, a system much more democratic than any regime in the world today, let alone those regimes that existed in the world at the time. Even in the so-called ‘democratic’ capitalist regimes women could not vote.

Well into the Civil War (1918-1921) and after, Soviet congresses continued to meet and decide on key questions. The Bolsheviks shared power in government until March 1918, when their Left SR coalition partners walked out, and shared power in the multi-party Soviets until much later. Of the first three commanders-in-chief of the Red Army – Muraviev, Vacietis and Sergei Kamenev – not one was a Bolshevik. As with the Red Army, so with the internal security police, the Cheka – it was staffed by as many Left SRs as Bolsheviks.

Soviet democracy was never abolished, but it de facto withered away amidst pressures of the Civil War. In 1921, with the economy and society in freefall after seven years of debilitating conflict, sabotage and invasion, the Communist Party congress brought in a temporary ban on factions – but not before yet another dynamic debate in the Bolshevik tradition, with Lenin supporting the ban but only as a temporary emergency measure.

One incident from this debate is worth highlighting. Lenin made a flippant remark about machine-guns. For this he was sharply criticised by a rank-and-file member, Kiselyov. For its tone and content, Lenin’s apology is worth quoting in full:

“Comrades, I am very sorry that I used the word ‘machinegun’ and hereby give a solemn promise never to use such words again even figuratively, for they only scare people and afterwards you can’t make out what they want. (Applause.) Nobody intends to shoot at anybody with a machine-gun and we are sure that neither Comrade Kiselyov nor anybody else will have cause to do so.”3

Under Stalin, a one-party monolithic state developed, the temporary ban was continued indefinitely and made into a virtue, and people actually were shot for their opinions.

The Land Question

The gulf between Lenin and Stalin goes even deeper. The greatest crime of the Stalin era was forced collectivisation and the ‘liquidation of the kulaks.’ This led to famine in the early 1930s. Vast masses of people were arbitrarily declared ‘kulaks’ (relatively rich peasants) and dragged away to the Gulag.

Any regime, socialist or capitalist, would have had to face the challenges presented by Russian agriculture. Lenin, too, grappled with these challenges. His conclusion after many struggles was that modernising the villages and bringing socialism to them would be the work of decades, and must proceed by rewards rather than coercion.

The relationship between the peasants and the early Soviet state was complex: there were peasants who rebelled against the Soviet government, and others who formed Red Armies and fought to the death for it.4 But even if we take Lenin’s policy toward the rich peasants at its most severe, it nowhere even begins to approach the inhumanity, crudeness and economic vandalism of the Stalin regime.

Progressive Lenin and regressive Stalin

The struggles against imperialism, racism and sexism were other key points of divergence.

There are today numerous Autonomous Republics in Russia which date from the revolutionary period – peoples such as the Tatars, Bashkirs and Buriats were conquered under Tsarism and granted their demand for autonomy under Lenin. By 1920, the Red Army had become a vast literacy school as well as an army; national minorities served in their own units, and were instructed, commanded and schooled in their own language.

Lenin always supported the right of nations to self-determination, and from day one of the October Revolution the Soviets called for Finnish and Polish independence. In 1919-21 they made treaties with the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, recognising their independence regardless of the fact that they remained capitalist. All five of these countries had been colonised by the Tsar. The Third International supported liberation movements worldwide. What a contrast to the countless millions killed in wars from India and Ireland in the 1910s to VIetnam and Angola in the 1970s as the empires tried to cling to their colonies.

Lenin’s final political struggle was with Stalin and his allies over the question of Georgia. Stalin, as People’s Commissar of Nationalities, took a crude and coercive approach to bringing Georgia into the Soviet Union, whereas Lenin favoured winning the consent of the Georgian people and working with indigenous communists.

When Stalin was in power, there were bans on minority languages, alphabets and religions. A generation of communists who came from Muslim backgrounds (such as Sultangaliev and Ryskulov) was wiped out. Entire populations such as the Crimean Tatars and the Chechens were attacked and forcibly transported. Even in the 1960s, long after Stalin, scholars researching their people’s history were persecuted as nationalist conspirators.

In parallel with the attacks on minorities came an attack on the majority – on Soviet women. The Revolution brought in the right to divorce, contraception and abortion. By contrast, Stalin banned abortion and promoted the conservative idea of women staying at home and having as many children as possible. LGBTQ+ people also saw an expansion of rights after the Revolution, followed by harsh attacks under Stalinism.

Once again the conclusion is obvious: Lenin and Stalin pushed in opposite directions on these key questions.

Civil War Violence

A superficially convincing argument is that the violence and repression necessitated by the Civil War set the stage for the violence and repression under Stalinism.

Unfortunately, the Russian Civil War is poorly understood. This war began in earnest when officers and Cossacks, who had been waging war without success against the new Soviet regime, began to receive serious assistance from foreign powers. For long periods these counter-revolutionaries, known as White Guards, controlled most of the territory of Russia. They received massive amounts of aid from Britain, France, the USA, Japan and others.

This was a complex and brutal war taking place in a collapsing empire. The war left Russia devastated by famine and epidemics: a working class of 3 million had been reduced to 1.5 million; major cities were half-deserted. All the contending factions emerged with innocent blood on their hands. Isaac Babel wrote of his time with the Red Cossacks in Poland in 1920: “The chronicle of mundane atrocity weighs on me relentlessly, like a heart disease.”5

It is easy to highlight some shocking incidents from the Civil War and to draw a superficial parallel with the crimes of Stalin. But this would be to ignore scale and context. The Stalinist terror and ‘liquidation’ campaigns claimed millions of lives, a number on a different scale entirely from even the highest estimates of Civil War terror on all sides.

During the Civil War, there was definitely cruelty and inhumanity on the Red side. But it began for the most part after three-quarters of the country was occupied by an implacable and ruthless enemy and subjected to White Terror. Years later, Stalin would impose a far greater terror in peacetime against unarmed, peaceable opponents (both real and imagined).

Stalin had a rigidly centralised state at his command so the atrocities of the day can be fairly blamed on his regime. During the Civil War, central authority was weak throughout large swathes of territory, and it was in remote places and on the initiative of local leaders that the worst excesses took place.

For the young Soviet state under such severe attack, draconian security measures were indispensable to survival. A significant part of the violence was nonetheless counter-productive or excessive. But the comparison between Civil War violence and Stalinist violence does not stand up to scrutiny.

Early in the Civil War when both sides could only field small forces, the Whites had the upper hand as they had many officers and veterans in their ranks. But as the armies grew in size later in the war, the Red Army grew stronger and the White Armies fell to pieces. This is because workers and peasants were inspired to fight for the Red Army’s programme of ending landlordism, championing national rights and opposing the old capitalist order. Meanwhile in the White Armies they found corruption, abuses and an uninspiring programme to fight for: restoring the landlords and bosses.

Did Lenin set a course toward Stalinism?

Even if everyone were to accept that Lenin and Stalin were fundamentally different in character and political method, that would not of itself answer the accusation that Lenin’s decisions set his country on an inevitable course toward Stalinism.

The fear, brutality and destruction of the Civil War certainly helped to create the conditions where someone like Stalin could rise. In particular, the near-disintegration of the working class in reality destroyed Soviet democracy and created a power vacuum for bureaucracy to grow. In his article ‘Better fewer, but better’ Lenin called the early Soviet state, before the rise of Stalinism, “deplorable, not to say wretched”, because of its bureaucratic features and its inheritance of the coercive and primitive Tsarist culture.

But did Lenin lay the basis for Stalin? The crudest form of the argument in favour of this proposition is that revolutionary violence crossed certain moral and ethical lines (such as suspending democratic rights, or executions without due process) which up until then had remained sacrosanct. Once these taboos had been violated by Lenin, the argument goes, the country was on a slippery slope toward Stalinism.

Crossing a line

But this is naive. In the First World War, the combatants used starvation as a weapon of war, bombarded cities to rubble, and forcibly expelled millions from their homes (like we see in Gaza today). Britain never had a single enemy soldier bearing arms on its soil. Nevertheless its government suspended democratic rights, shot suspected enemy agents, tortured conscientious objectors, and ran an all-pervasive regime of censorship and mindless jingoistic propaganda.

And then there is imperialism: the governments of Britain, France, Belgium, Germany, the United States and Japan killed, bombarded and burned without moral scruples in their colonies, or let famines rage on a scale that may have shocked even Stalin.

Back at home, almost every ‘democratic’ country in the early 20th Century limited voting rights based on race, gender or property. This is all common knowledge. If the violation of certain moral taboos sets a state on a course toward totalitarianism, why did such a regime come to power in Moscow but not in Paris, London or Washington?

In reality, in war and statecraft, there were never any moral or ethical taboos. The rise of Stalinism had bigger causes, which we will examine below.

Was the Revolution ‘too extreme’?

A more sophisticated argument is that Lenin’s plans were fundamentally unrealistic and extreme; the contradiction between what he was trying to do and what was possible in semi-feudal Russia led to Stalinism. Such views are even put forward in leftist and socialist quarters.6

You’d almost forget, listening to these commentators, that there existed in Russia mass movements and organisations, notably the elected soviets, of workers, peasants, women, military personnel and nationalities. These movements were motivated by urgent demands that placed them deeply at odds with the landlords and bosses. With or without Lenin and the Bolsheviks, a revolutionary situation existed. What Lenin did was bring it to the point of a successful revolution. If he hadn’t done so, there would have been instead a counter-revolution to destroy these popular movements and organisations, in order to restore ‘business as usual’ for the landlords and big business. It would be truly unrealistic and extreme to imagine such a counter-revolution being achieved without massive violence.

Who started the Civil War?

It is sometimes argued that the October Revolution was politically too extreme, and was bound to generate a backlash and a Civil War. In turn, the Civil War devastated the country and killed Soviet democracy, setting the stage for Stalin to make his grand entry.

Were Lenin and his comrades responsible for starting the Civil War? No. In fact, the Civil War was started by a cabal of military chiefs, who gathered around them a few thousand officers and Cossacks. This shower of reactionaries not only lacked the support of the population, but held 90% of the population in utter contempt and did not seek their support. Although the destruction they wrought led to hunger and epidemics, none of these small armies was able to make any headway militarily until first German then Allied intervention in 1918. For these generals to rebel in arms with the support of only a small minority; for Britain or France to give a million rifles to warlords and adventurers – these were conscious choices which had dire consequences for millions of people. To blame these choices on the Soviet government is just perverse.

International Revolution

Parallel to this, we get the arguments that Lenin’s economic policy was too extreme, and that his belief in imminent international revolution was unrealistic.

The early Soviet government did embark on a massive and swift state takeover of industry. Taking industry into public ownership is a key plank of a socialist programme, but because of the chaotic conditions in the country, right up to Spring 1918 Lenin and his party favoured gradual nationalisations and a secondary role for the private sector. But sabotage, capital strikes and lockouts by the employers led to workers demanding nationalisation as the only way to save their jobs and workplaces. At the same time, with food supplies devastated by World War and Civil War, the Soviet government sent out bands of workers to seize surplus grain, which kept the cities fed at the cost of conflict with farmers. These should be judged as emergency measures.

Lenin said and wrote many times that the revolution would definitely fail if it did not spread to other more developed and industrialised countries. As if in mockery of this prediction, the only other country to which the Revolution successfully spread was Mongolia – a sparsely-peopled nomadic country. So was the entire revolution based on a false prediction?

The thing is, revolutionary situations did arise in Germany (1918-1923), Hungary (1918-19), Italy (1920) and a range of other countries. The social democratic leaders in those countries betrayed their own supporters by holding back these revolutions. The German ‘socialist’ leaders even worked with far-right paramilitaries to bait and then violently suppress the revolution in Berlin in January 1919. Unlike the Bolsheviks, the revolutionary left within the western social democratic parties was too scattered and disorganised to prevent this. History could have taken a totally different course, with Mussolini and Hitler as the mere footnotes they deserved to be, if these opportunities for democratic socialist revolution had not been betrayed.

That year even saw Soviets in Ireland and Scotland. Britain (1926), China (1925-7) and Spain (1931-7) represented later opportunities. These revolutions were defeated – often at the cost of unleashing fascist regimes – but in 1918-1923 the situation really did hang in the balance. The potential for international revolution was far from a figment of Lenin’s imagination.

If the Russian Revolution had been spared the catastrophe of full-scale Civil War, and / or had been joined in an international socialist alliance by even a handful of more developed countries, then Soviet democracy could have survived or even flourished. The Stalins of this world would have remained the obscure figures they were in the early years.

Was Lenin’s achievement futile?

Some readers may respond that it doesn’t matter how Stalinism came about or whose fault it was – the tragic and depressing result, Stalinism, renders the whole effort futile. But this is hardly a balanced view.

First, Stalinism even at its worst did not entirely roll back the October Revolution. Unlike Tsarist Russia, there was free healthcare and social insurance, massive public investment in housing and access to education for all. Despite all its evils, Stalinism never went back to square one. Millions lived who would have died in infancy; tens of millions lived richer and better-educated and freer lives than their parents. All this, because the key gain of the October Revolution – a publicly-owned and planned economy – remained in existence.

At his death, Lenin was deeply uneasy about where the Revolution was going. But even at this late date the rise of Stalinism was not straightforward or inevitable. After the Civil War there was a period of calm and toleration. The Cheka (internal security police) were radically cut down – two-thirds of its staff was let go. Use of the death penalty ‘diminished into insignificance’ after the Civil War. In 1927-8 the prison population was under 200,000 – compared to 1.2 million in the United States in 2021.7

There was a truly remarkable economic recovery after the New Economic Policy was adopted in 1921. The Opposition within the Communist Party gathered strength, demanding industrialisation and a return to Soviet democracy. Stalinism was far from the only possible outcome. It was not some malice or madness in the mind of Lenin, or any defect in the character of the Russian working class, but such momentous events as the failure of the Chinese Revolution of 1925-7, the rise to power of Hitler in Germany, and the defeat of the Spanish Revolution that cemented the position of the Stalinist bureaucracy.

The world-historic achievements of industrialising the Soviet Union and of defeating Nazi Germany belong to the Stalin period. But they are not points in his favour. Terrible waste, overwork and inefficiency marred the five-year-plans to industrialise Russia. And on the eve of the war with Nazi Germany, Stalin was in an alliance with Hitler, had murdered all the best military commanders in the Red Army, and had left the rank-and-file soldiers still bitter over forced collectivisation.

In other words, Stalin’s bureaucratic regime meant that these achievements came at a far greater cost than was necessary. Even so, these were great achievements, and they would have been impossible without the planned economy and popular regime established by the October Revolution.

Conclusion

Stalinism had big and deep-rooted causes: the underdevelopment of the young Soviet Union and its inheritance of the old semi-feudal culture; the devastation caused by the World War and Civil War; the failure of revolutions in other countries, and the Soviets’ prolonged isolation in a hostile world. We could point to mistakes and excesses of secondary importance, such as the 1921 decision to ban factions, which certainly smoothed Stalin’s path to power. But the rise of a tyrant and a bureaucratic dictatorship is only adequately explained by the broader conditions outlined above.

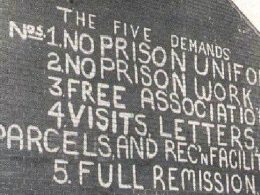

The Stalinist state used Lenin’s image relentlessly in statues, movies and paintings, giving the overwhelming impression that there was continuity between Lenin and Stalin. Those opposed to socialism, and eager to associate socialism with notorious characters, promoted the same idea. Once Stalin had been safely dead for three years, his own protégés denounced him as a tyrant. But they kept up the main features of Stalinism, such as one-party bureaucratic rule and repression. Unarmed workers protesting against high prices in Novocherkassk in 1962 carried portraits of Lenin; this did not stop snipers and machine-gunners from opening fire and killing dozens of them.

Because of the way Lenin’s image was used and abused by the Stalinist regime, there is a lot of confusion out there. But the truth of what Lenin stood for is a sufficient counterweight to a hundred years’ worth of propaganda.

Notes

[1] See John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World. This classic journalistic account of the Revolution mentions Stalin only accidentally and in passing. [2] Vadim Z Rogovin, 1937: Stalin’s Year of Terror, Mehring, US (1998), p 287-8 [3] ‘Remark On Kiselyov’s Speech Concerning The Resolution On Party Unity March 16’, The Tenth Congress of the R.C.P.(B.) March 1921, Moscow, (1933) https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1921/mar/08.htm[4] The Taman Red Army, for example, was composed of poor peasant tenants of the Kuban Cossacks. On the other side, peasants in Tambov Province revolted against the Soviet power in 1921

[5] Isaac Bebel, Red Cavalry, 1926, Pushkin Press, 2014, p 59 [6] Domenico Losurdo, War and Revolution: Rethinking the Twentieth Century, Verso Hinge Points Episode 5: Goodbye, Lenin – podcast available on Patreon. [7] Peter H Solomon Jr., ‘Soviet Penal Policy 1917-1934: A Reinterpretation’ Slavic Review, Vol. 39, No. 2 (Jun., 1980), pp. 195-217https://www.jstor.org/stable/2496785?read-now=1&seq=8#page_scan_tab_contents