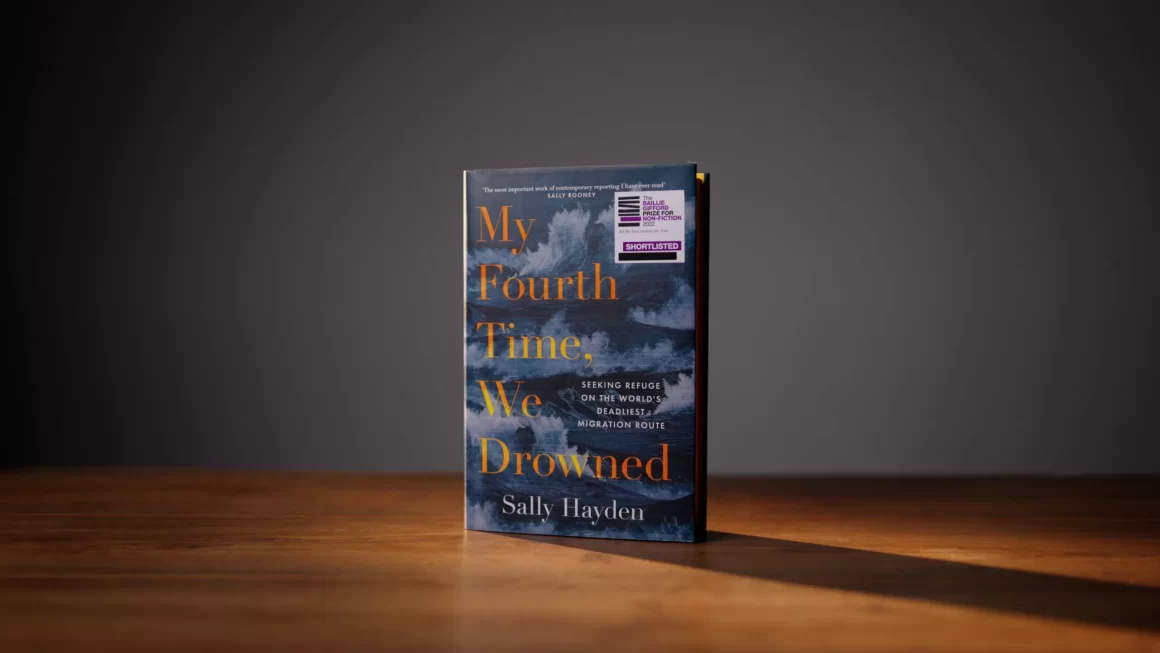

Review: My Fourth Time, We Drowned

By Sally Hayden

Fourth Estate, 2022

Reviewed by Michael O’Brien

For the recording of testimony alone, from migrants from sub-Saharan Africa about the hardships they endured attempting to come to Europe for a better life, this book and its author Sally Hayden richly deserve the accolades and awards already bestowed upon it.

However, this book achieves more than providing an important platform that serves to fully humanise the people who put everything at risk to improve their and their families’ lives. It is an indictment of institutions such as the EU and United National High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR), which are portrayed in the West in benign progressive lights.

Hayden herself, who would be familiar to readers of The Irish Times for her consistent excellent reporting from Africa, is justifiably part of the ‘story’ contained in the book. Her reputation had already spread sufficiently that in August 2018 she began receiving facebook messages from an Eritrean migrant incarcerated in one of the detention centres in Libya, which is part of an entire apparatus to support the objective of ‘Fortress Europe’ – the policy of preventing, by the crudest means imaginable, the migration of people fleeing war, conscription, persecution, grinding poverty and the effects of climate change.

These factors, which are ultimately located in the unequal capitalist relations between the developed and neo-colonial world, drive migration, and coupled with the legal and physical barriers then put up by the EU to impede the movement of people create a niche for human traffickers.

These criminals charge enormous sums in return for the promise of a successful passage to the Mediterranean coast and across the sea to Europe. The reality, as told to Hayden, is that even when the passage to Libya is delivered upon it is frequently accompanied by the migrant being treated as a hostage and attempts made by the traffickers to extort more money from the migrant’s family on pain of being tortured or raped.

Once in Libya, assuming they make it to a rubber dinghy and are pushed out to the Mediterranean, they are then faced with a hazardous trip which in the last decade has resulted in tens of thousands of drownings.

The agreement the EU has reached with the Libyan authorities is one of effectively equipping the coast guard to prevent the boats arriving in international waters and the mass incarceration of migrants picked up at sea. In these Libyan prisons the abuses and privations match those perpetrated by the traffickers.

Hayden time and again confronts the EU authorities with the testimony she receives from migrants. The reality is that behind the ‘progressive’ veneer, the measures the EU has in place leave Donald Trump’s openly racist and widely condemned border wall and childrens’ detention centres in the shade.

Likewise with the UNCHR, under whose very nose in Libya these abuses have taken place. It is not an understatement to say that this agency of the UN is revealed to be rotten to the core. The salaries and expenses of its personnel compared to its actual practical output of processing refugees is an abomination. Key officials effectively victim-blame incarcerated migrants who have justifiably rose up in protest against their conditions.

Even if the UNCHR was genuine in its mission we still have the problem that the governments in the developed world are only prepared to receive a token amount of refugees who follow the routes described in Hayden’s book.

Governments, in particular the Italian and Greek, have gone so far as to criminalise activists and ordinary people who provide any life-saving or humanitarian assistance to migrants while they attempt their hazardous crossing.

Insofar as one can obtain any inspiration from the book it is the resourcefulness of the migrants in being able to organise themselves and work with Hayden to get their stories told, and at critical moments generate sufficient political pressure to force even temporary improvements in their situation.

A number of the migrants with whom she was in contact from the time of their incarceration in Libya did make it to Europe. This does not represent the end of their struggles as they have to adjust to a new life, often in the context of a hostile political environment, while not having fully processed the trauma of everything they went through over a period of years – not to mention the enduring separation from their loved ones.

Since this book was published we have witnessed a spate of anti-migrant activity in Ireland. The far right is reliant in some measure on the ‘othering’ of migrants, particularly of migrants of colour, in the eyes of the audience they want to influence with their racist ideology. Books like this are a significant contribution in revealing the humanity of those prepared to risk it all, but also situating these personal stories in their wider political and institutional context which, while not veering in the direction of articulating a political programme that addresses the politics of migration, does point in the direction of the global system of capitalism and its institutions that need to be done away with.