By Mikey Rose

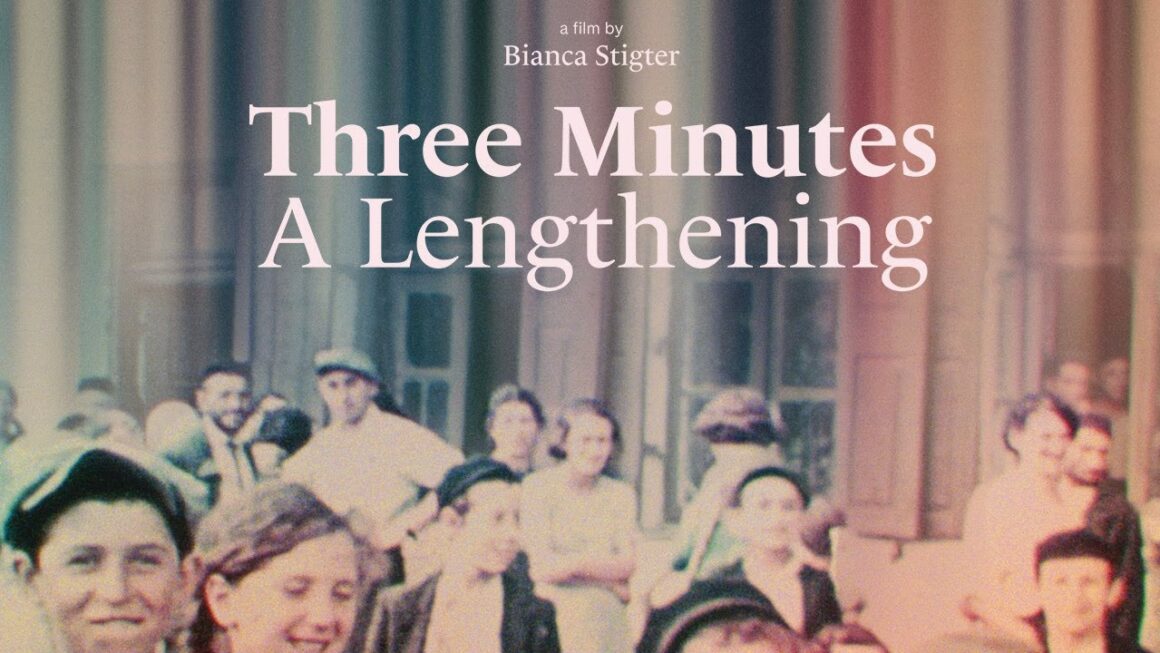

Three Minutes: A Lengthening is a 2022 Dutch–British documentary directed by Bianca Stigter and narrated by Helena Bonham-Carter. It recounts the historical process of digitally restoring and deciphering three-minutes of 16mm film featuring snippets of the Jewish community in Nasielsk, Poland, in 1938, one year before the Nazi invasion. The footage was filmed by David Kurtz and recovered by his grandson Glenn Kurtz in 2009.

The three-minute clip is played at the start. The smiling faces of children wrestling for a shot in front of the camera beam through the screen. Adults step out of doorways to see what’s happening. And the restored colour presents this Jewish community in Nasielsk from 1938 as if it were recent memory. For an hour, I watched this clip play forward, backward, looped, frozen and framed. At the start it’s just a three minute clip, there’s no context, the faces represent a mass, and the town is an isolated point of history. An hour later, these three minutes have become a lifetime, and a foreboding precursor to an immense social tragedy.

I sat with my parents to watch this film about Polish Jews in 1938. My mum’s grandparents had fled the country only a couple of years prior having already faced exclusion from their work. Through our familiar eyes we recognise instantly the huge door of a synagogue in the town, as well as the mezuzahs on the door. We notice that there are no members of the ultra-religious sects in the streets and are wise to the distinction of cheder boys and working youth.

Three Minutes present as an isolated point in time, but this time is part of a larger historical and social context. The film represents an effort to bring these three minutes into relation with its context, so that we might better understand what’s excluded by its isolation from history. The Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 represented the stark advancement of fascist imperialism by German capitalism, leading to the brutal subjugation and exploitation of the Polish people. Among the Polish working class was a relatively large population of Polish Jews, who were targeted for persecution and extermination by the Nazi regime.

The invasion of Poland marked the beginning of the Holocaust, during which millions of Jews and other minorities were systematically murdered by the Nazis. As socialists, we call for working-class unity and international solidarity to fight against fascism, racism, and imperialism. By situating the Jewish community of Nasielsk in its wider historical context, this movie examines the consequences of remaining alienated from each other and of allowing the capitalist forces to divide us. It reminds us of the importance of solidarity and collective struggle against oppression and exploitation, and of the need to build a society that prioritises the needs and interests of the working-class and oppressed people.

While watching this film, we were tuned not only to what was to come, but what was already beginning. While Nasielsk may not have been my great-grandparents’ hometown, their figurative absence was not only foreboding, but formed a context for those who were present but unable to leave. The beaming faces captured in the short footage already had fascism at their doorstep. It would be another year before the Nazis arrived, but the looming threat was steadily progressing. For instance, the narrator highlights a missing lion mould on the door of the synagogue caused by the vandalism of local fascist gangs. The ideology is already present, it just doesn’t yet have the ruling class behind it.

The videographer captures the footage from an outsider perspective. While this was once his home, he now stands behind the camera rather than before it. We have to understand the context in which he arrives as the producer of the footage. His arrival in 1938 demonstrates a mobility inconceivable not only to the residents of the town, but also to the majority of people in Europe. In a period where my great grandparents urgently sought to flee, he arrived with his family on holiday. This town may once have been his home, but due to social and economic circumstances his fate is at this point very much disconnected from it. This highlights the ways in which the social and economic structures of capitalism create inequality and disconnection between people and communities, as well as the role that class plays in shaping our experiences and perspectives.

Three Minutes is clear however that it is not his perspective that we should follow. The power of this restoration is in drawing our attention to what’s missing, or in what’s behind the images. The videographer’s three minutes captures beaming faces and local buildings as objects, but the ‘lengthening’ explores the movements of its edges and absences. The frames of the camera show us that these people were, that the town was, but they don’t tell us what or why. The film does an excellent job, if perhaps underdeveloped, of working to fill these gaps, drawing attention to the array of social relations, exploring how they shape the history of this town and its people.

By focusing beyond these people’s faces, and onto their clothing, for example, we see relations of class, industry, and labour. The different types of hats worn by young boys in the film express class relations, with thin-brimmed hats worn by students and cloth hats worn by young workers. The array of buttons on shirts and dresses become related to employment in the local Jewish-owned button factory. This emphasises not only the degree of class stratification among the Jewish population in Nasielsk, but also the potential of the factory as a space open to Jewish labour in 1938, in a context of widespread exclusion. The film contrasts this with the same factory in 1939, which becomes occupied by the Nazis to produce wear for the military, while the class relations of the Jewish population are eviscerated as they become unified through brutalisation and deportation.

Those beaming faces will be dimmed, we know, by events to come, but the videographer is oblivious. As the film zooms into a frozen frame of the town square, we are exposed to a testimony which details the mauling of Jewish residents before they are marched to the train station (to be deported to various ghettos and ultimately extermination camps).

The clearest and most striking absence that we become aware of by watching this film is that of solidarity from the wider working class of Nasielsk and Poland generally. Despite fascism’s threat to all sections of the working class in Poland, the Jewish community becomes isolated from the rest of the town’s people. In this testimony we hear how the Jewish community was looked upon with pity and disgust by onlookers as they were marched off by the Nazis.

As socialists, we recognize the importance of solidarity among the working class, across all lines of race, religion, gender, and nationality, in order to build a united front against fascism and capitalist exploitation. The absence of solidarity from the wider working class meant that the Jewish community was left vulnerable to the violence and persecution of the Nazis. This tragedy serves as a reminder of the urgent need for solidarity and collective action among the working class in the face of fascism, racism, and imperialism. We must unite in our struggle for a society that prioritises the needs and interests of the working class and oppressed people.

Just as the Jewish population of Nasielsk must be regarded as a part of the wider working class oppressed and exploited under capitalism, rather than isolated from it, this film demonstrates the importance of understanding all moments in time as connected to a larger historical and social context, and a wider process of historical and social development. This requires us to examine the contradictions and conflicts that shape the development of society over time, and to identify the social and economic structures that underpin them.

Through this approach, we can gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics of social and historical change, and of the ways in which different struggles and movements are interconnected and interdependent. This perspective allows us to build solidarity across different communities and struggles, and to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the world around us. By situating the Jewish community of Nasielsk within this wider context, this film underscores the importance of solidarity and collective action in the face of oppression and exploitation.