By Martina Gergits & Paul Gerrard

We live in times of crises. The effects of the climate crisis are being felt more and more. As extreme weather events including forest fires, floods and heat waves occur with increasing regularity, showing glimpses of a horrible new “normal” of climate catastrophe, it is clear who is being hit hardest by the climate crisis — the working class. At the same time, the ruling class, in governments and business, does nothing. They are not at a loss for excuses: “it would be too expensive.” Yet in Germany, for example, 100 billion euros have been released for rearmament without batting an eyelid. The money is there, but it is being misused. The contradictions of capitalism make it clear that it is all about making a profit at our expense.

One industry where this is very clear in relation to the climate crisis is the car industry. For decades, corporations in the automobile industry, together with the oil industry, have been among the top 10 of the 500 most powerful corporations. They exploit workers, countries, and the environment in many ways. They determine how people move around, roads dominate cities and landscape. 25 percent of CO₂ emissions come from transport, and mainly from individual transport. Moreover, a study showed that air pollution caused by vehicle exhausts is responsible for hundreds of thousands of premature deaths every year; the related global health costs were approximately US$1 trillion in 2015. Worldwide, about 10 million jobs depend on the automotive industry, which equates to about 5 percent of the world’s jobs, and typically for any directly employed worker another four are indirectly dependent according to the International Labor Organization.

For decades the car industry has argued that switching to climate-friendly production means a reduction in profits and will therefore cost jobs. In doing so, they are playing climate off against jobs, and trying to divide the working class and the climate movement. However, already before COVID, the automobile industry went into crisis in 2019 and corporations have been cutting jobs to push profits for decades. In this context, the role of climate change was used as an excuse to hide the anti-worker strategy of the bosses.

Today, car manufacturers are rushing to produce electric cars and other vehicles. They are not doing this for the climate. The reasons are simple: on the one hand they need a new sales market. The market for the combustion car is practically saturated, and a new technology that is massively supported by governments delivers far more profit. Now that China is massively promoting the electric car, the car industry lobby in Europe and the US is following suit to keep up. It is not about the climate: it is about profits.

The e-car has a bigger CO2 footprint than the combustion engine when it leaves the factory, not to mention the question of how the electricity is produced that is needed for charging. And the e-car has fewer parts, needs fewer work steps and in capitalism that means fewer jobs and therefore more profit for the corporations. The massively promoted e-car does not answer any of the urgent questions, neither jobs nor climate.

Who decides what is produced and what a transition of production can look like?

As so often, we can learn from history. In January 1976, workers at Lucas Aerospace in Britain published an Alternative Plan for the future of their corporation. In the 1970s Lucas Aerospace employed 18,000 workers across 17 sites in the UK. Fifty percent of its production went to defence contracts.

The Lucas Plan came out of a time of trade union militancy, often among workers who were defending their jobs against cuts, “retrenchment programs,” “rationalisation,” etc. In 1971 the workers at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (UCS) in Glasgow occupied their yard, continuing to produce ships; the stand they took had a powerful effect on trade union activists. There was a wave of factory occupations in engineering plants across the North of England, and in 1972 a miners’ strike, followed by a second one in 1974, which effectively brought an end to Heath’s Tory government. The militant workforce at Lucas Aerospace, who had already taken strike action over pay, were hoping the incoming Labour government would solve the issue of job losses by public ownership, which could lead to a different set of priorities and enable them to develop a wider range of products.

In November 1974 the Joint Shop Stewards Combine Committee met with Tony Benn, Secretary of State for Industry in the Labour government, to demand that the projected nationalisation of the aerospace industry would include Lucas Aerospace, as part of a wave of capitalist nationalisations, including British Shipbuilders and British Leyland, which included most of the British car industry. These were all under pressure from an emboldened trade union movement. However, Lucas Aerospace was left out of the newly formed British Aerospace in 1977. Benn challenged the Committee to come up with an alternative strategy for the company, which is what they did. The Committee’s Alternative Corporate Plan was produced in 1976.

The Financial Times described the Lucas Plan as “one of the most radical alternative plans ever drawn up by workers for their company.”

What made the plan so radical?

Firstly, because the Shop Stewards Committee asked the workforce for ideas. The Lucas Aerospace workers came up with no fewer than 150 ideas for products, many of them highly innovative and including some which, looking back over fifty years, capitalism has signally failed to explore, and that are only now being fully developed under the pressure of the climate crisis, such as heat pumps, wind turbines and alternative transport systems such as vehicles that would operate on both road and rail. Many others were grouped specifically under the heading of energy-saving devices which would nowadays have a high priority.

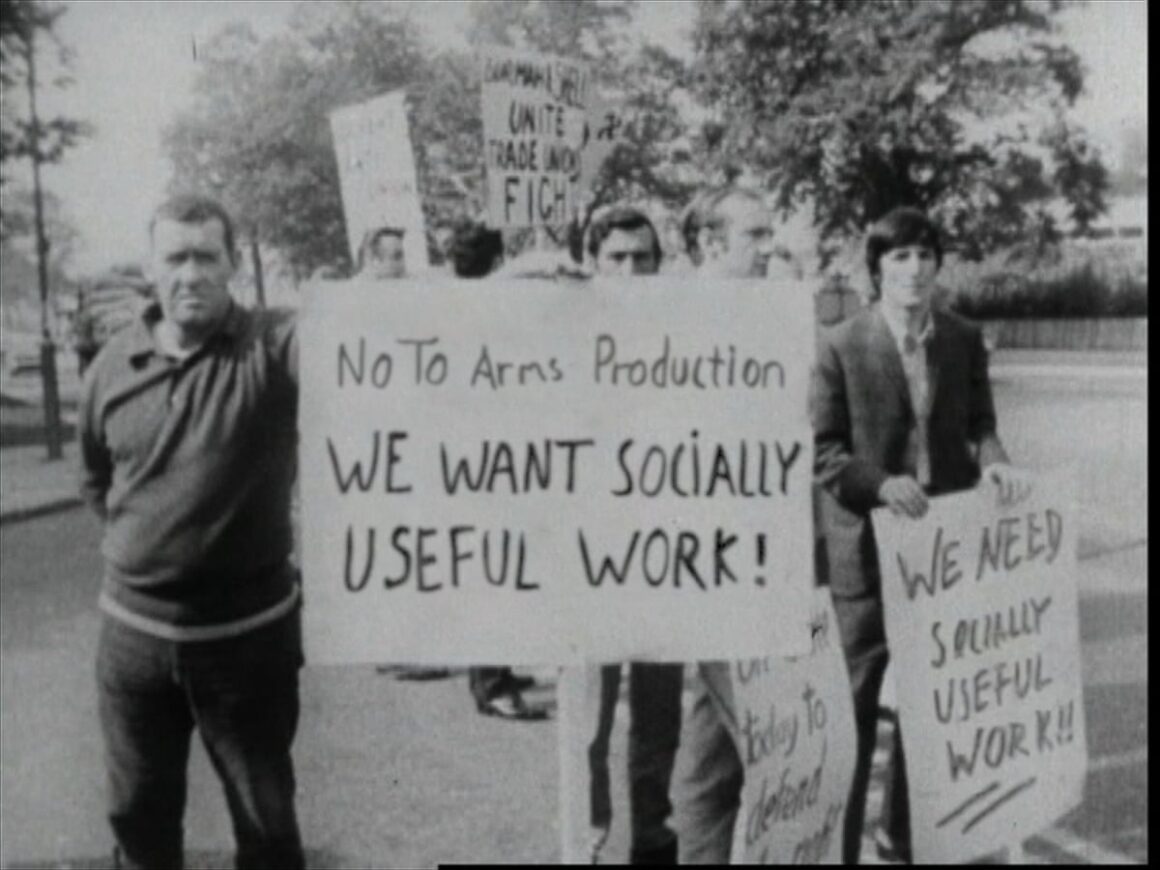

Secondly, because the workers focused on the idea of “socially useful work.” In the media campaign that accompanied the launch of the 6-volume plan they counter-posed jet fighters to dialysis machines, highlighting the frustration of a workforce involved in making machines to kill people when they could be making machines to keep people alive. In doing so they were drawing attention to the skewed priorities of a profit-based system.

Thirdly, the activists responsible for bringing the plan together found themselves increasingly questioning the nature of work in a capitalist economy and emphasised the need to overcome the alienation of the workforce through collaboration of technical, shop floor and administrative staff, and by re-organising work into less hierarchical teams that bridged divisions between theoretical expertise and the under-acknowledged knowledge of the shop floor.

Tony Benn, who had shown interest in the Lucas Plan, and was later to emerge as a leading figure on the left of the Labour Party, had been moved to another ministry. The trade union bureaucracy was not eager to promote the plan given that it emanated from the rank-and-file and challenged both traditional demarcations and the management’s “right to manage,” a policy often challenged by shop stewards but defended by the bureaucrats.

While Lucas Aerospace was left out of the nationalised British Aerospace, the entire corporation was privatised by the incoming Tory government in 1980. This was part of the launch of neoliberalism and attacks on trade unions and workers’ rights under Thatcher.

Had the Labour Party and the union leaderships taken their task seriously, and at least supported the workers and rank-and-file union organizers in their efforts to reshape production, it could have created a real momentum for the movement. The Lucas Plan nevertheless catalysed ideas for the democratisation of technological development in society and generated widespread discussion and enthusiasm among shopfloor workers.

The Lucas Plan, an excellent example of how the decision to convert production can be made, had an impact in Germany. The trade union IG Metall took up the idea of the Lucas Plan at Blohm & Voss Hamburg and set up the first working group on alternative production in the coastal region shaken by the shipyard crisis. By the end of 1983, about 40 such company working groups had been set up, not only in shipbuilding and the defence industry. The demands went further and included a restructuring of the company decision-making structures. In Germany, too, neither management nor government were enthusiastic about the workers’ plans. As with the Lucas Plan, it quickly became clear that the goals of the working groups could not be achieved at the company level alone.

Although supported by a still broad peace movement, the approach of arms conversion did not prevail, given the priorities of the ruling class. The demand for cross-company working groups did not materialise, partly because the IG Metall did not coordinate them. The trade union leaders concentrated on the traditional, conventional collective bargaining and corporatist crisis policy.

However, corporate policy does not only consist of making decisions on the product range, but also by exercising power over the means of production. As long as these remain untouched and in private hands, we will remain in the current mode of production, based on exploitation.

So, the key elements we need for a successful transition are:

Fighting back

The Lucas Plan was a response to management announcements that thousands of manufacturing jobs were to be cut in the face of industrial restructuring, international competition, and technological change. Instead of redundancy, workers argued their right to socially useful production. For the first time, a trade union struggle to save jobs was linked to a struggle to develop a new product range.

There is a similar situation today in the automotive industry, among others, where jobs have already been cut since 2019 and production sites are being closed.

Here, too, the question arises: how can jobs be preserved, and climate-friendly production be achieved at the same time?

The IG-Metall trade union in Germany expects that about 400,000 jobs of the current 1 million jobs in Germany will be cut. But the answers of the union leaders are just as misguided as the strategy of the companies. While the bosses decided to transition the production to the electric car, using the climate to conceal that they are doing it for profit, the union leaders are trying to defend the status quo by location protection and accepting lower wages and job cuts. But instead of accepting the “rules of capitalism,” the unions and especially the workers, need to develop a plan on how production can be transitioned. It is the only way to save the environment and jobs.

It needs to be a collective decision about what and how much is produced, starting with the workers in the factory with the know-how and skills and the communities they are part of. This was the core of the Lucas Plan. Workers were right to fight for their right to socially-useful production, instead of producing for the military. To produce what is needed in the area should be the standard not the exception. Production should serve the needs of society.

Also today, resistance is already stirring: in Munich, a Bosch plant that mainly produces parts for diesel engines is to be closed. Climate activists showed solidarity with the workers and together they fought the closure of the plant and demanded a change in production. This is what a common struggle for jobs and climate can look like.

The management, as so often, argued that a change of production is too expensive. But during COVID, SEAT, GM and Ford converted their production practically overnight and produced ventilation equipment for patients on assembly lines where otherwise chassis were assembled. In the Second World War, the Cadillac plant in Detroit converted from making luxury cars to tanks in 55 days. When the class that controls production decides, it happens. Another good reason for workers to decide production. The know-how of the workers made it possible.

Building a movement

Shop stewards at Lucas consulted their own members but did not stop there. Over the course of a year, they built up their Plan on the basis of the knowledge, skills, experience, and needs of workers and the communities in which they lived. In promoting their arguments, shop stewards at Lucas attracted workers from other sectors, community activists, radical scientists, environmentalists, and the Left. The Plan became symbolic for a movement of activists committed to innovation for purposes of social use over private profit. Workers’ councils networked not only across several locations but also across several sectors, even to other countries.

The shop stewards at Lucas were never under any illusions that the company would implement the plan. As in Germany it became very clear that could not be achieved at the company level alone. Reaching out to other companies, with concrete demands, and at the same time building and organising a workers’ movement that is capable to ensure the implementation of the demands against the will of governments and corporate managements, is key.

The climate movement today is young and militant, and aware of the urgency to fight against climate change. The movement managed to effectively drag the climate issue into the public eye. Starting with the Green New Deal, it was present in almost every election debate. The movement’s appeals to governments wedded to capitalist profits will not succeed. After two years of demonstrating and student climate strikes, all the ruling class says is “blah, blah, blah.”

Workers and environmentalists need to organise and rebuild a fighting climate movement that is closely linked to a fighting workers’ and trade union movement. A united struggle would link the transition to climate-friendly production with the fight for climate justice.

Imagine a climate strike in which workers from industry participate not only individually but in an organised way, joining the student climate strikes by going on economic strike for climate protection, green jobs, higher wages and better working conditions? How much would that cost the climate-destroying corporations?

For example: A 40-day strike at General Motors in the US against a plant closure in 2019 cost the company $2 billion. This strike illustrates that the working class can challenge and win against the power of any big corporation if we get organised and fight back. The movement needs clear bold demands, democratic structures and a strategy to win.

Fight for Workers’ Control

The Lucas Plan demonstrated to all the world the skill, knowledge, ingenuity and creativity of the working class. The Plan in the UK, as well as the approaches in Germany, failed because of the constraints of the existing production conditions. Management, as well as governments, prevented the workers’ plans and there was a lack of support from the union leadership for the fight of their own rank and file members. The root of the contradiction lies in the property relations: who owns the means of production decides. A fundamental change in production can only be achieved by transforming property relations and who owns and controls production.

In the absence of any prospect of nationalisation, the Lucas workers began to explore other avenues around the concept of workers’ control. This was a period of ideological ferment in the trade union and labour movement, and also much confusion. The real power that workers exercised through the shop stewards’ movement, often with some control over production speeds, seemed to offer the prospect of a long-term and even a permanent challenge to the management’s right to manage. Pamphlets and proposals for workers’ control or, in its more moderate formulation, “industrial democracy” were legion. There were widespread syndicalist views among union activists. There were, for example, illusions in the “socialist self-management” practised in Yugoslavia under Tito and Djilas, where workers were able to influence board decisions and received a portion of a factory’s revenue.

However, it was left to Marxists to explain that as long as private profit rules, decisions about the range of products and production methods will be subordinated to the profit motive. The true realisation of workers’ control can only take place on the basis of the social ownership of the means of production, with workers’ management across society, involving the unemployed, young people, pensioners, etc.

As for the car industry, the transition to the e-car is not the answer. What is needed is an entirely new concept for public transport. Massive expansion and improvement of public transport that is free of charge, car sharing, possibly restricted to e-cars, public e-bikes, fully electrifying the railway and so on, powered by electricity generated from renewable sources not fossil fuels or nuclear power. This change will provide good, secure and rewarding jobs, and at the same time create environmentally-friendly mobility for the climate and drastically reduce toxic pollution. This change will only be possible if industry is publicly owned, controlled, and run by workers. That’s true for the automotive industry, as for any other key sector of the economy.

And by changing the ownership of the means of production, we challenge capitalism itself. As Marx said: “At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or — this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms — with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.” (Marx, Preface to the Critique of Political Economy, 1859)

The working class is the only force in society with the power to overthrow the capitalist system and to replace it with a democratically planned socialist economy. The only way to slow the worst effects of climate change and begin to reverse the damage already done is to build an independent mass movement of workers and youth fighting for a socialist transformation of society, one that puts the real needs of people, the planet, and all life at the centre.