By Councillor Leah Whelan

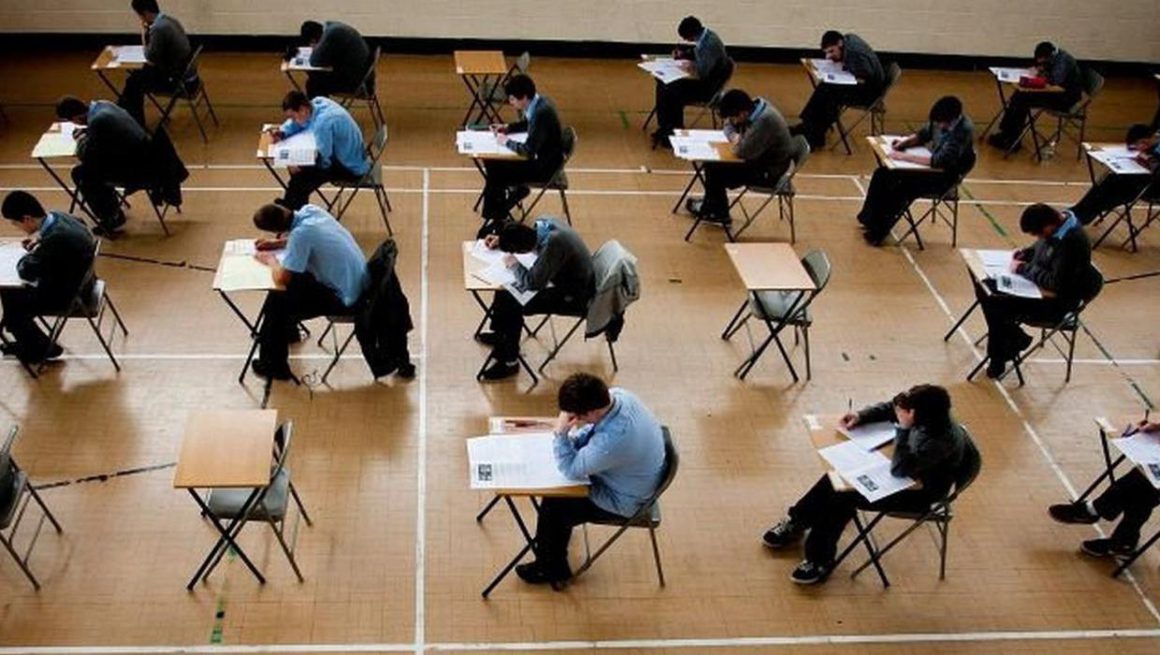

The year has begun with a massive spike in Covid cases in schools and throughout society. Naturally, there is huge uncertainty about what the next months will bring for exam year students and teachers.

Sixth-year students still face the prospect of a traditional Leaving Cert (LC) in 2022. The government shouldn’t force students to compete in an outdated, stressful and unequal exam, especially under the current Covid conditions. However, on a normal year, the LC is still outdated and stressful. The Minister for Higher Education, Simon Harris, revealed last year that “The current Leaving Cert system does not prepare students for life beyond school”

Despite the comments by Harris, and Covid having a major impact on students’ ability to learn, the government wants to plough ahead with a traditional exam this summer. The cut to in-person teaching over the course of three school years has left current sixth-year students without a full, uninterrupted year of school since the junior cycle. Clearly, this has an effect on the students’ ability to complete vital coursework, and ultimately, sit a traditional LC exam.

The previous sixth-year students, who faced exams in 2020 and 2021, had to mount a challenge, and put significant pressure on the Ministers for Education and the government, in order to win changes to the examination. This resulted in students not being forced to sit the traditional LC and had the option to get predictive grades, calculated by their teachers, or sit a pared-down version of the exam. It was indicative of the ability of students to win change when they got organised in a campaign.

Competition for third-level education

Those students organised through different initiatives such as social media storms, mass email campaigns and raising students’ voices through social media. Although they won important changes on the exams from the pressure applied, there were problems. The predicted grade system leaves teachers with the responsibility of grading their own students. In previous years, this has created point inflation, leaving many students without a college place anyway, due to a lack of spaces.

The predicted grade/hybrid system does not address the issue at hand, which is the chronic underfunding of third level: with a mere 0.06% of GDP invested into colleges and universities. Contrast this with the billions given to businesses during the pandemic. As a result of underfunding and under-resourcing, colleges struggle with staffing issues due to tutors and lecturers being on temporary contracts.

The under-resourcing has a domino effect on the Central Application Office (CAO). The CAO offers roughly 55,000 places for 80,000 applicants. This is what drives competition in schools. The idea of competition is a necessary aspect of the LC that allows the government to kick the can down the road on what’s actually needed overall to address the issues in third level. What we need to combat this shortage of places is to properly fund and massively expand third-level education, including investment in apprenticeship courses. The state needs to properly fund educational services, including moving tutors and lecturers onto full-time permanent contracts. Linked to this, no one should have to pay fees for attending a third-level institution or doing an apprenticeship.

The stress and pressure created by competition and the scarcity of places put students into an unnecessary battle with their peers. Even in pre-pandemic times, the LC had a debilitating impact on students. The UN Committee on the rights of children has described it as traumatic!

What’s needed

What is needed is for the Irish state to allocate proper resources to colleges that allow students to progress their education if they wish to. The current system of competition needs to be replaced with a system of open access. Open access is a policy that will allow all students to get a place in third level, ensuring that the funding is provided.

In addition, students should be provided with a living grant and affordable accommodation where necessary.

This would require billions in extra funding, which can be raised through taxes on super-wealthy individuals and corporations that have profited massively during the pandemic. Billionaires increased their profits by €17.4 billion during the pandemic. The richest 300 people in Ireland have a combined wealth of €93.7 billion — even a levy of 10% would make significant developments in infrastructure and staff.

Similarly, the government must provide more apprenticeships for students who wish to learn a trade. Local councils are currently desperately in need of apprentices.

In addition, Ireland is facing a shortage of teaching staff, nurses and healthcare staff. Opening up college spaces would allow for the labour shortages to be filled, and give everyone a chance to achieve their potential. Similar to how second-level education was opened up to all in the 1960s. Some countries have better systems in place, albeit not perfect. The Netherlands and Switzerland allow all students to progress from secondary to third level with no examinations.

Young people strike and protest

This year’s sixth-year students have witnessed sixth years before them put pressure on the government for changes. However, this year is the first time we will see students organise in-person protests, strikes and other actions for 19 January, the day the Dáil reconvenes. It is important that students collectively organise in a safe way, and put their demands forward clearly. Students have the advantage of making a big statement to the government through the walk-outs, demonstrations and online actions they’ve planned for the coming days. A range of protests have been planned for Dublin, Wexford, Waterford and other places across the country.

Young people have been at the forefront of many issues including Black Lives Matter and the Fridays for Future strikes. If students want real systemic change, they need to understand that real pressure from below brings about such change. This starts with people organising on the streets, in their schools and workplaces.