In May 2021, as Gaza was under another murderous assault by the Israel state, a major wave of solidarity protests with the Palestinian people swept the globe. This was combined with protests and a general strike of Palestinians in Gaza, the West Bank and within Israel’s borders. This naturally brought the question of ‘how the Israeli state can be defeated?’ to the fore of people’s minds. Here, Peter McGregor looks back at the lessons from the First Intifada, one of the most important examples of Palestinian resistance.

The bombardment of Gaza lasted 11 days. Over 250 people were killed and over 1,000 injured. This happened in the context of the ratcheting up of assaults on Palestinians by the Israeli state in East Jerusalem and Sheik Jarrah. One harrowing tweet brought home the devastation and terror that Palestinians were facing: “Tonight, I put the kids to sleep in our bedroom. So that when we die, we die together and no one would live to mourn the loss of one another.”1

Looking back at the First Intifada that erupted in December 1987 can assist in answering the aforementioned question, particularly in light of the emergence of a new mood of defiance. This was best exemplified by the protests and general strike of Palestinians in response to the barbarity of the Israeli war machine. The Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, reported on the impact of the strike:

“The Israel Builders Association said Palestinian workers had observed the strike, with only 150 of the 65,000 Palestinian construction workers coming to work in Israel. This paralyzed building sites, causing losses estimated at 130 million shekels (nearly $40 million). But even before the strike, since the beginning of the operation in Gaza, only 6,000 to 8,000 Palestinians were coming to work every day. According to Yehuda Katav, vice president of the builder’s association, construction has slowed to a snail’s pace. ‘We cannot build without them’.”2

This, coupled with the various other protests that took place in Sheik Jarrah and all across the occupied territories, and the international outpouring of solidarity all provide hope for a movement against the occupation.

40 years of dispossession & occupation

The Arabic word ‘intifāḍah’ literally means ‘shaking off’, and given its association with key struggles of the Palestinian people is generally understood to mean uprising. The First Intifada was exactly that, an uprising in an attempt at shaking off years of colonialism, occupation and brutal repression. It began when an Israeli settler crashed his truck into cars in the Gaza Strip, killing four Palestinian workers on 8 December 1987. This event was the spark, but a piling up of unbearable conditions created the tinder that produced a powerful flame.

The Intifada took place 40 years after the ‘Naqba’ in 1947, which saw the expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland with some 750,000 forced to flee their homes, and just over 20 years after the occupation of the remaining Palestinian land in 1967, beginning a steady process of further ethnic cleansing of Palestinians through the building of settlements. Having experienced over four decades of war, dispossession and daily injustices, a new generation began to say ‘enough is enough’.

From 1967 through 1987, approximately 200,000 Palestinians passed through Israeli jails. At the time, Gaza’s population was 500,000 and over 400,000 were refugees. Thirty-six percent of land in Gaza was controlled by 2,500 Israeli settlers, and 50% of land in the West Bank was either in the hands of 65,000 settlers or used by the military.3

What was the intifada

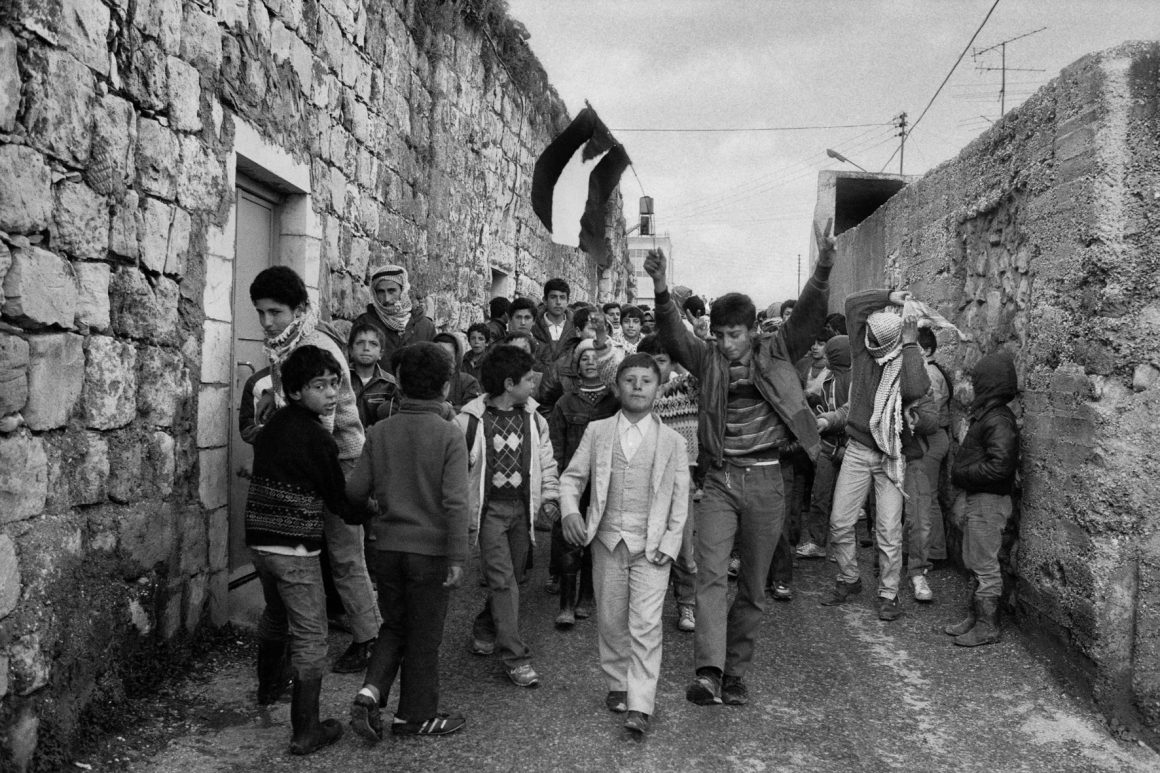

The First Intifada began as mass demonstrations in Gaza, which spread to the occupied West Bank. The demonstrations utilised the methods of mass struggle – protests, strikes, even riots. A coordinating committee was set up (the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising) alongside local popular committees that organised the struggle from the ground up.

The Intifada was based on an active revolutionary movement of young people, workers and women. It ended with the signing of the Oslo Accord in September 1993, which constituted a historic betrayal of the struggle for Palestinian national liberation by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) leadership. However, the intifada showed that working-class people can shake to the core an oppressive state, even one as vicious as Israel, which killed over 300 people in the first year of the intifada alone.4

Many of those involved in the grassroots committees were members of trade unions and left-wing organisations, and they used their positions in relation to the Israeli economy to make the revolt as effective as possible. The most powerful tool any workers have is strike action, as it stops production which in turn hurts capitalists’ profits. Palestinian workers availed of that fact on 22 December 1987 with a general strike of Palestinians in Israel. The New York Times said, “Hundreds of thousands of Arabs inside Israel joined others in the occupied territories today in a general strike protesting Israel’s handling of a wave of protests.”

It continued: “great numbers of Arab laborers who wait on tables, pick vegetables, haul garbage, lay brick and perform most of Israel’s menial work stayed home. More than 100,000 workers from the occupied territories go into Israel each day, in addition to the Arabs living there, filling a vital role in the Israeli economy.”5 This, coupled with a boycott of Israeli goods by Palestinians in January 1988, is estimated to have cost the Israeli economy £28 million,6 equivalent to around £68 million today.

Committees of struggle

Notwithstanding the spontaneity at the beginning of the First Intifada, organisation of the movement was crystalised quickly. By January 1988, grassroots committees had been set up which went about organising food storage and distribution, healthcare, special needs of their villages, etc. In a recent interview one veteran of the uprising said, “had the Coronavirus outbreak happened in the First Intifada, it could have been creatively contained. The spirit of social solidarity would make each person believe they have a duty”.7

These committees took matters into their own hands and placed no hopes in the leadership of the PLO, which at the time of the First Intifada was in exile. Researchers have pointed out that the years leading up to the Intifada saw a massive increase in protests in Palestine, while “faith in a solution driven by external actors, like the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), based in Tunis, and the Arab countries, had declined.”8

In genuinely shaking the Israeli regime, the Intifada highlighted two vital things: first, that working-class and oppressed people, when organised and mobilised en masse can be a powerful force, and second, that mass struggle proved more effective than the counterproductive methods of the PLO in the past or Hamas today — with their use of individual terror attacks.

The role of women

The active role of Palestinian women in struggle laid some of the foundations for the organisations and programmes that were used during the First Intifada, for example the first women’s committee was created by working-class women in 1978 in Ramallah in the West Bank.9 Such women’s committees were an important part of the revolt, as outlined by Maura K. James in her paper ‘Women and the Intifadas: the Evolution of Palestinian Women’s Organizations’, in which she states:

“While women all over Palestine participated in what Penny Johnson and Eileen Kuttab call ‘”mother activism”… when older women sheltered youth and defied soldiers’ the formal societies kept the intifada in motion from the top. The women’s unions ‘participated in distributing the secret communiqués of the Unified Leadership, delivered PLO funds for social relief, visited prisoners and their families, and performed other activities…”10

In the fantastic documentary Naila and the Uprising directed by Julia Bacha, the role that women played is again brilliantly displayed. Women distributed bulletins in bags of bread, set up schools for Palestinian children, sourced products from Palestine in order to make the boycott of Israeli goods, alongside the general strike, as effective as possible, and much more besides.

The documentary also details the effect that the revolt had in Israeli society, with an Israeli journalist explaining how a section of Israelis saw the need to support the uprising, including for example a protest by Israeli women who wore all black to “mourn ‘justice’, which has been violated by the occupation.” There was also a march of several thousand Palestinian and Israeli women who went from West Jerusalem to East Jerusalem, crossing the divide, at which Naila Ayesh said, “Double your efforts to lift the injustices from my people, so my son and your son, and all children can live side by side.”

Following these kinds of protests, along with the Palestinian uprising itself, pressure on the Israeli ruling class began to mount. WithinIsrael many ordinary working people realised that Palestinian resistance meant that the occupation or annexation of the West Bank and Gaza was unviable and untenable . Support began to grow for a separate independent Palestinian state rather than incorporating the occupied territories into a “greater Israel”.

Role of the youth

Young people were central to the revolt. They were the first to throw stones, be involved in committees and were active in their schools and universities. Student activity and the spreading of radical ideas flourished from the 1970s as more Palestinians began to attend university. As Jack McGinn writes: “From the universities spread radical ideas of popular democracy; unions were set up to organise within the student body and the wider community in tandem with other sectors of Palestinian society.”11

However, it was not just through student bodies that young people were active in the resistance, it was also in political parties and in community work. According to Rula Salameh, a student at Birzeit University: “when the intifada began, there wasn’t a single student who hadn’t joined a political party on campus. All students spent their time and energy helping their community and working towards the collective mission of liberating Palestine from Israeli occupation.”12

At the time of the Intifada Palestinian society was very youthful. In 1987 in the West Bank 47.2% of people were under the age of 15, and 20.7% were between 15 and 24 years of age. In East Jerusalem in 1988, 41.7% were under 15 and 20.6% were between 15 and 24, and in Gaza in 1987, 48.8% were under 15 and 19.9% were between 15 and 24.13

Such a youthful population is not always precondition for an uprising, however it certainly plays a role in accelerating it, particularly when a young generation is faced with no real future. Young people are often the most open to radical ideas and willing to take determined, dangerous action. This is due to many factors: a sense of fighting for their futures, a freshness to activity untainted by experiences of leadership sell-outs, their conditions of exploitation in the workforce, their experience of injustice in education and in social lives, and many other things.

The Palestinian population today still has a youthful character. In 2019, 38.7% of the population were under 15 and 20.3% were between 15 and 24. It is safe to assume that the same potential for youth to be at the forefront of any coming struggle is there. The mood after 30 years of totally bogus talk on the part of the Israeli ruling class and imperialism of the creation of two states, implying an end to the occupation, coupled with the lived reality of repression, political betrayal, and in the context of a movement against oppression within Palestine and internationally, is still a strong one.

Right to self defence

With the First Intifada, the crucial effect and importance of mass struggle became clear. In response to such mass struggle, regardless of how peaceful and disciplined it is, Palestinians have faced and will face military backlash from the Israeli state and therefore have a right to armed self defence. However, this should not be in contradiction to the mass movement, but rather an auxiliary to that movement wherever Palestinians are being fired upon.

Arms and ammunition should be democratically controlled by grassroots committees of struggle, which would allocate, distribute and decide how the arms are used. These methods of armed defence, which are used in conjunction with the most effective methods of working-class struggle, are juxtaposed to the futile and counter-productive methods employed by the PLO leadership in the past and today by Hamas. Such methods became prominent in the Second Intifada, which developed in response to the sellout of the Oslo Agreement. Instead of the mass action seen in the First intifada, individuals and organisations in desperation resorted to acts of individual terrorism and even suicide bombings targetting Israeli military and civilians.

Such methods are incapable of defeating the Israeli state, which today has a military budget of over $17 billion.14 In part this is because it drives Israeli workers into the hands of the Isreali ruling class and ultimately strengthens, not weakens, the hand of the latter. Secondly, because it points away from the mass struggle and the tactics that are necessary.

Lessons for Today

The Oslo Accords which were signed in 1993 and 1995 were a sell out of the movement by the PLO leadership who, behind the backs of the active movement on the ground, entered into talks with the Israeli government, facilitated by the government in Norway. The agreements established the corrupt Palestinian Authority, which instead of an ending of the occupation simply made Fatah (the dominant faction of the PLO led by Yasser Arafat) responsible for managing the occupation. Their forces were trained and armed by the CIA, and have worked hand in glove with the Israeli Defence Force in maintaining the occupation, blockade and oppression of the Palestinians.

In light of the experience of the heroic First Intifada, the question must be asked: why didn’t this mass struggle defeat the Israeli state? The primary reason is that, ultimately, while an intifada based in the occupied territories can have a major impact, it cannot defeat the Israeli state on its own. This is why the Palestinian liberation struggle should reach out to other sections of the working class in the Middle East, as part of a region-wide struggle to overthrow the various dictators and corrupt regimes, along with imperialism, along with the capitalist order on which they are based.

However, crucially, in order to defeat the Israeli ruling class, any such movement must seek to exploit the cracks in class-divided Israeli society, in which millions of Israeli-Jewish workers do not have the same interests as their corrupt rulers. In Israel since the start of the pandemic 268,000 households have fallen into poverty and the cost of living is the eighth highest in the world.15,16 Racism against Ethiopian Jews is real. It’s also important to note that within Israel’s officially recognised border there is a sizeable Palestinian workforce in key sectors such as health, transport and construction.

If a Third Intifada is to succeed, a revolutionary force within the occupied territories that can lead and counter the influence of the rotten forces of Hamas and Fatah is needed. If such a force is based on a strong socialist and internationalist programme it could make an appeal to working-class Israelis, and inspire a struggle to end the occupation and overthrow Israeli capitalism, and defeat and expel imperialism.

A democratic, socialist solution based on the empowerment of the working class and oppressed would ensure that the national rights of both Palestinians and Israelis are upheld and that the rights of minorities are guaranteed. It would mean the creation of an independent, socialist Palestine with its capital in East Jerusalem and a socialist Israel based on free and open borders. This could be linked to a struggle for fundamental socialist transformation of the Middle East, where the impoverishment and exploitation of its working population could be ended for good.

The First Intifada remains a testament to the enormous sacrifice and heroism of the Palestinan people who have time and again shown a willingness to defy oppression, strike back against colonial settlements and continue to fight for self-determination against a mega military force. But it is also a vital example of mass struggle from below, which is unquestionably the way forward for the movement for Palestinian liberation.

Notes:

1. Eman Basher @SometimesPooh, 12 May 2021, twitter.com

2. Lee Yaron, 19 May 2021, ‘General Strike Highlights Israel’s Dependency on Palestinian Workers’, Haarets, www.haaretz.com

3. Peter Hadden, 1988, ‘Palestinian youth revolt’, Militant Irish Monthly, No. 159N, www.marxists.org

4. J. Peters & D. Newman, 2013, The Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Routledge, p. 61

5. By John Kifner, 22 Dec 1987, ‘A General Strike By Israel’s Arabs Disrupts Country’, New York Times, www.nytimes.com

6. ‘Economic Aspects of the Intifada’, www.civilresistance.info

7. Nadia Naser-Najjab, 6 Aug 2020, ‘Palestinian leadership and the contemporary significance of the First Intifada’, ww.journals.sagepub.com

8. Baylouny & Anne Marie, 2010, ‘The Palestinian Intifada’, The International Encyclopedia of Peace, Oxford University Press

9. Melinda Cohoon, 2014, ‘Palestinian Women of the Intifada: the Women’s Committees, 1987-1988’, Portland State University

10. Maura K. James, March 2013, ‘Women and the Intifadas: the Evolution of Palestinian Women’s Organizations’, Strife Journal, Issue 1 2013, pp. 18-22

11. Jack McGinn, Non-Hierarchical Revolution: Grassroots Politics in the First Palestinian Intifada, Oxford Middle East Review, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Trinity 2021)

12. Mersiha Gadzo, 11 Feb 2018, ‘What happened to Palestine’s youth-led struggle?’, www.aljazeera.com

13. United Nations, June 1994, Population and developments in the West Bank and Gaza Strip until 1990, www.unctad.org

14. Business Insider India, 13 July 2021, ‘The world’s 20 strongest militaries’, www.businessinsider.in

15. Sue Surkes, 9 Dec 2020, ‘Number of Israelis in poverty shot up 50% since pandemic’s start, report finds’, Times of Israel, www.timesofisrael.com

16. Ynet, 2 May 2020, ‘Israel ranked eighth most expensive country in the world’, www.ynetnews.com