By Sean Burns

The hunger strikes of 1980-81 and the events preceding them, was one of the many horrific chapters in the Troubles, and arguably helped create a new spiral of conflict and violence lasting for more than a decade. The Thatcher government’s decision to allow ten prisoners to slowly starve themselves to death was a barbaric and callous act, a testament to the real nature of her regime and the British ruling class she represented. Those who survived the strike would be inflicted with long-lasting damage to their physical and mental health. It naturally enraged many in the North and provoked mass anger further afield, notably in the United States, where dockworkers refused to handle British goods.

This was a period of intense sectarian polarisation, state violence and rioting which resulted in many deaths at the hands of the police, including children and teenagers such as eleven-year-old Carol Ann Kelly killed by soldiers’ plastic bullets following the death of hunger striker Patsy O’Hara. Others died as a result of atrocities committed by paramilitaries. Joanne Mathers, a young Protestant mother of one, was shot dead by the IRA in Derry, while collecting census forms, the day before Bobby Sands won the Fermanagh / Tyrone by-election. Patrick Martin, a Catholic shopkeeper, was murdered by the UDA for closing his shop and attending the funeral of Francis Hughes.

The approach of the British state drove a section of young people into the dead-end of paramilitary organisations like the IRA and the INLA, and saw the development of Sinn Féin as a political force. The price for the failure to resolve the prison crisis was paid by workers, both Protestant and Catholic, who had to suffer through a period of heightened tensions and violence.

Special Category Status to Criminalisation

Special category (or “political”) status (SCS) was de facto prisoner-of-war (POW) status, providing prisoners with some of the privileges of POWs. This meant prisoners did not have to wear prison uniforms or do prison work, were housed alongside their paramilitary factions, and were allowed extra visits and food parcels. This was one of the conditions set by the Provisional IRA when they negotiated a meeting with the British government to discuss a truce. The 1972 Hunger Strike was undoubtedly a factor but not the key reason for this being introduced. It was an attempt by the British government to buy time to restore order to Northern Ireland by trying to secure a temporary truce.

The granting of this status also took place against the background of massive instability in the North. Parts of Derry and Belfast were still no-go areas for the British army and other state forces up until July of that year. However, by the mid-1970s, there existed, in the words of Northern Secretary Reginald Maulding, “an acceptable level of violence”, as far as the British ruling class was concerned. It felt increasingly confident that it could deal a major blow to the IRA after the ceasefire of 1975-1976, which was disastrous for the IRA. In the words of Maulding’s predecessor, Roy Mason, boasting in 1978, the British state was “…squeezing the terrorists like rolling up a toothpaste tube”.

In 1976, the British government moved to remove SCS for prisoners in Northern Ireland. This was part of their dual approach of “Ulsterisation” and “Criminalisation”. In essence, the British state was moving away from relying on the Army to maintain order in Northern Ireland and towards the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) as the prime enforcers. SCS presented an obstacle to this as it undermined the narrative that those imprisoned were simply engaged in “gangsterism”, as Merlyn Rees, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland put it, or as Margart Thatcher more bluntly put it: “crime is crime is crime”.

The response of the Provisional IRA was foreshadowing of what was to come: “We are prepared to die for the right to retain political status. Those who try to take it away must be fully prepared to pay the same price”. It sent out a message that prison guards were now considered “legitimate targets”.’ The removal of SCS was linked to the construction of the Maze Prison, known locally as the H-Blocks. The withdrawal of SCS would provoke rioting and shootings in both loyalist and republican areas, but it proved insufficient to reverse the decision.

Prison protests begin

The first prisoner sentenced under the new policy arrived at the Maze and was ordered to wear a prison uniform. He was IRA volunteer Kieran Nugent. Nugent refused to wear the uniform, saying he was not a criminal but a political prisoner. He was locked in his cell where he wrapped himself in the blanket that was on the bed rather than remain naked, beginning the ‘Blanket Protest’. By 1978, nearly 300 republican prisoners were refusing to wear prison uniforms. As these tactics resulted in stalemate, the prisoners escalated their protest to ‘No Wash’ protests, over the refusal to install showers in cells and violence by prison guards. After prisoners were vindictively refused permission to leave their cells to “slop out”, i.e. empty their chamber pots, the ‘Dirty Protest’ began. The TV images of emaciated prisoners in their cells, wrapped in blankets, with the walls covered in their own excrement, graphically exposed the regime of repression that existed in the H-Blocks. This eventually gave way to a number of prisoners going on hunger strike. Loyalist prisoners would also engage in protest and disruption over the withdrawal of SCS.

The protests were a product of the dire conditions inside the H-Blocks, where prisoners faced routine human rights abuses — the brutal policies of the Thatcher Government, and, shamefully, also of the Labour governments of Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan between 1974-1979. These prisoners were mainly convicted in non-jury courts under special legislation. Many were convicted solely on the basis of confessions given after violent interrogation in police detention centres. Amnesty International and even the British government’s own Bennet Report exposed the horrific techniques employed to force the signing of confessions. Inside the H-Blocks, stories of cruelty and misery were widespread.

The prison protests were borne out of sheer desperation. On the outside, despite the threats of the Provisionals, their campaign of bombing and shootings proved unable to secure concessions from the British state. They could not achieve British withdrawal nor secure gains for prisoners. In fact the opposite would prove to be the case. Their campaign laid the groundwork for more and more repressive powers to be utilised, as the IRA became more and more isolated. It gave the state the space and excuse to introduce increasingly repressive measures and for those measures to become normalised. The use of diplock courts, in which the democratic right to trial by jury was abolished, plastic bullets and live ammunition all became the norm in Northern Ireland. The deadlock of the prison issues pushed the prisoners to utilise the one resource they had left — themselves.

Hunger Strike

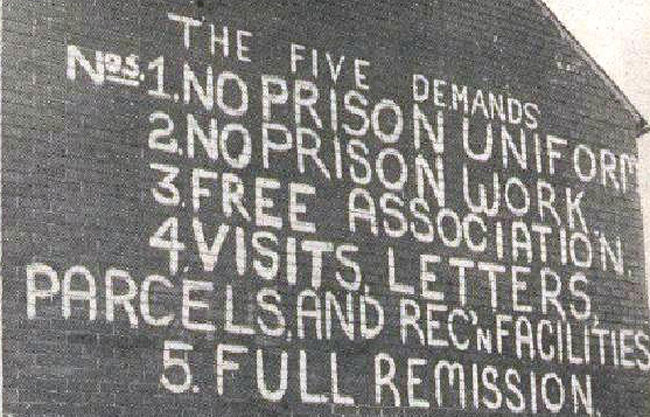

On 27 October 1980, a hunger strike began with seven republican prisoners in the Maze, shortly followed by three republican prisoners in Armagh women’s prison. They put forward five demands for the ending of their protest: 1. the right not to wear the prison uniform; 2. the right not to do prison work; 3. the right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits 4. the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week; and 5. full restoration of remission lost during the protest. Loyalist prisoners joined the protest. They stated that they wanted all five republican demands and an additional one: to be separated from republican prisoners. This hunger strike would end with one man in a coma, close to death and the promise of reform on the part of the British government. A promise they would renege on.

When it became clear that the demands were not being met another hunger strike was initiated by republican prisoners. This time it would be staggered, with Bobby Sands the first to go on hunger strike.

The deaths in the prisons were entirely preventable. Yet the Tories refused to budge. Thatcher demanded unconditional surrender, nothing less. The Tories could have averted or ended the hunger strike at any stage. The prisoners demonstrated that they would have accepted less than political status and a more just reform of the prisons. In a statement during the hunger strike they said: “It is wrong for the Government to say that we are looking for differential treatment from other prisoners. We would warmly welcome the introduction of the five demands for all prisoners.” (4 July 1981 prisoners statement)

H-Block Committees

During the Hunger Strikes, the issues at stake were viewed as issues for one community alone. Militant, the Socialist Party’s predecessor, opposed this view. Repression in all its guises is a class issue. A united working-class movement seeking to end the rule of capitalism must ensure that all its repressive measures and instruments of oppression are actively opposed. The same state weapons used against Republican and Loyalist prisoners in 1981 could just as easily be utilised against socialists and trade unionists of all community backgrounds. Shamefully, the leadership of the workers’ movement in the North, the South and in Britain remained largely silent on this issue throughout the Troubles, fearing it was inherently divisive. In some cases, it even supported state repression.

While the Tories bore the prime responsibility for the tragedy in the prisons, the campaign of the hunger strikers would also highlight the weakness of the one-sided campaign of the H-Block Committees. This does not take away from the courage of these activists, who were targeted by Loyalist paramilitaries.

The leadership of the H-Block Committees based themselves on the idea that it was necessary to win the unity of the Catholic population. They appealed solely to “nationalist” groups, including right-wing and reactionary politicians. They organised conferences to tie together parties such as the SDLP and Fianna Fail, which was in government in the South overseeing an administration of poverty, inequality and repression themselves. Such an approach applied a straitjacket of sectarianism to the movement for prison reform.

Provisional’s campaign dead end

Coupled with this the H-Block support groups were associated with the PIRA. This prevented them from being able to mobilise mass support on a consistent basis. Contrary to the romanticised view presented today, the IRA’s support amounted to only a minority of the Catholic minority, and whatever the IRA’s stated intention, the reality of its armed campaign was to stoke the flames of sectarianism, increasing divisions amongst Catholic and Protestant workers.

It was hard to disguise this sectarian edge when car bombs destroyed the centres of largely Protestant towns. At other times, the Provisionals’ campaign was nakedly and viciously sectarian, for example in the period of 1975-76 more than 60 Protestant civilians died in sectarian attacks.

Even when the actions of IRA volunteers were not intentionally sectarian, the campaign as a whole was objectively sectarian and acted to deepen division rather than break it down. When members of the state forces were targeted, such as UDR soldiers or prison guards, this was viewed as an attack upon the Protestant community and drove it further into the hands of the state.

The funeral of Bobby Sands drew a crowd of between 70,000 and 100,000 people. This huge attendance did not reflect support for the Provisionals, but a genuine sympathy for the plight of the prisoners and total opposition to the Tories’ intransigence. One Derry worker summed up the mood in Catholic areas at the time as “anti-Provo, anti-IRSP, pro-Bobby Sands”. Two months later there were less than 10,000 following the coffin of Joe McDonnell. An important reason for the decline was the massive state repression at funerals and protests. However many were repelled by how the events were used as recruitment opportunities for republican paramilitaries.

How repression could be defeated

It was not inevitable that the support for the plight of the prisoners would find itself reflected through the one-sided approach of the H-Block Committees. The inaction of the trade union leadership, which had the capacity to unite Catholic and Protestant workers, allowed these issues to become so one-sided. Throughout the Hunger Strike, ICTU issued just one statement and proceeded to engage in the most deafening of silences.

In the context of Northern Ireland, opposing repression can be a difficult task. The pitfalls of sectarianism are very real. Particularly in the 1980s when tensions were high. But it is possible to unite workers of all backgrounds against state repression, precisely because it is in the interests of all workers to oppose repression. The journalist Robert Fisk famously recounted that, shortly before Bloody Sunday, he was in Belfast and witnessed paratroopers viciously beat Protestants in the Shankill Road area after they had blocked a street with vehicle tyres, peacefully protesting over a lack of security. All workers experienced repression and all workers could oppose it.

The position of Militant laid out an approach that could have united workers across the divide. First by advocating a “programme of prison reform to cover all prisoners which would have included the right to wear their own clothes, to negotiate choice of work and training and education, access to the media, unrestricted numbers of letters and trade union rates of pay.”

At the same time it argued that the workers’ movement should establish “an inquiry to review the cases of all those convicted of offences arising out of the Troubles.” This could have established who had been convicted on the basis of a frame-up or torture through the police interrogation centres or the Diplock “non-jury” courts. It would also have allowed the workers’ movement to decide who was and wasn’t a political prisoner, and then campaign for the release of “political prisoners and those falsely imprisoned, but on the proviso that it would not fight on behalf of sectarian murderers.”

Who exactly would be deemed to be given the status was an important question and could not be left in the hands of paramilitaries. It could not be given to those Loyalists who were guilty of heinous sectarian atrocities such as those carried by the Shankill butchers, or those IRA members who were guilty of atrocities such as the Kingsmill massacre, who as it happens were never convicted. A working-class movement and party that united the Protestant and Catholic working class on the key issues impacting the lives of ordinary people, would have the capacity and authority to determine this question. The trade unions, which organise workers from both communities in mixed workplaces could have played this role. Such a movement would demand the release of those convicted on the basis of forced confessions and non-jury trials, as well as those who were deemed to be genuine political prisoners, including those who were convicted for engaging in direct conflict with the state.

Militant in Ireland and Britain actively took up the repression in the prisons before and during the hunger strikes, primarily by arguing for its program inside the trade union movement and in a manner that could win the ear of both of Catholic and Protestant working-class and young people, an approach that differed from others on the left who either tail-ended the Republican movement or wanted to ignore (and even support) state repression. For example, Militant members moved a motion in Derry Trades Council in June 1980, which called for:

“1. The right not to wear prison uniforms.

2. The right not to do prison work.

3. Freedom of association among political prisoners.

4. The right to organise recreational and educational facilities, to receive and send out one letter per week, and to receive one parcel per week.

5. The restoration of remission.

Derry Trades Council supports the above demands but believes that they do not only apply, to the abominable situation in H-Block, but apply to the prison conditions in the Crumlin Road, Armagh and Magilligan. Derry Trades Council again calls for a trade union inquiry into prison conditions generally.”

Similar motions and resolutions were put forward by our members in trade union organisations throughout the period from 1979 to 1981.

In Britain, Militant set up the Labour Committee on Prison Conditions in Northern Ireland, which won the backing of leading members of Labour’s left at the time, such as Tony Benn, Eric Heffer and Joan Maynard, and trade union leaders such as Sam McCluskie (National Union of Seamen) and Emlyn Williams (National Union of Mineworkers). During the hunger strikes, a Militant member and the Young Socialists representative on the Labour Party National Executive Committee, after visiting the H-Blocks, successfully moved a resolution which adopted Militant’s position outlined above.

Importantly, this was in the context in which the Labour Party leadership of ‘left winger’ Michael Foot was engaged in a policy of uncritically supporting the Tory government’s criminal policy. This shameful stance of the official labour leaders helped to overshadow the principled socialist and anti-repression stance adopted by the Labour Party’s NEC, taken at Militant’s initiative. Days before Sands’ death the Labour Party Northern Ireland spokesperson, Don Concannon, visited the H-Blocks and told the hunger strikers that the Parliamentary Labour Party would de facto support Thatcher’s stance on the strike.

Ballot box and armalite

An Important element of the H-block campaign was running candidates for election. When Frank Maguire, independent nationalist MP for Fermanagh / South Tyrone died suddenly, Bobby Sands was nominated to stand for the seat. Weeks before his death he was elected MP with over 30,000 votes, reflecting the deep chord of sympathy and support which had been struck among the Catholic community. The British government responded by banning prisoners from standing, yet the support for the prisoners continued after Sands’ death with the election of Sinn Féin member Owen Curran standing as “Anti H-Block / Proxy Political Prisoner”. Later in the southern general election, of nine prisoners who stood, two were elected and an impressive total of 40,000 votes was polled.

In this regard the republican movement stumbled on the dual strategy summed up by Danny Morrison as, “ballot box in this hand and an armalite in this hand we take power in Ireland.” In the 1982 Assembly election it polled 10% of the vote and 13% in the 1983 Westminster election, including the election of Gerry Adams in West Belfast. These votes were a reflection of the anger in Catholic working-class communities at the brutality of Thatcher’s response to the hunger strikes and to the conditions they faced of poverty and repression.

This led to an important shift in the republican movement, with Sinn Féin becoming the dominant component and a policy of abstentionism (refusing to take seats in a parliament) being dropped, for example in the southern Dáil. The contradiction in this strategy would be exposed in the years to come, when the so-called ‘successful’ actions of the IRA, such as Enniskillen Bombing, would undermine support for Sinn Fein.

Many from the republican tradition and others argue that the shift in the strategy of the IRA marked a turn of Sinn Féin away from radical politics. This is a superficial understanding. In reality the veneer of radicalism was beginning to slip. At its core the tactics of what Marxists call ‘individual terrorism’, the tactics organisations like the IRA practiced, are based on the notion that it is possible to bomb capitalism into submission, by targeting high profile figures, members of the state apparatus and infrastructure projects. From capitalism’s point of view, however, all individuals are expendable and replaceable. The removal of a single cog does not halt the whole machine. One Tory luminary, Lord Hailsham, indicated this: “when one was in Cabinet we did say to one another that if anything was done to any of us he was expendable and expended. I think that was right.”

Just as the liberal politician sees change occurring by a shake up of individuals in a government cabinet, so too does the individual terrorist see change by the removal of this or that representative of the capitalist state. Neither base themselves on the capacity of workers to transform society. The switch to an electoral strategy by Sinn Féin and the IRA followed this logic. The strategy became one of seizing the halls of power through the ballot box, not the armalite, and to do so conforming to the logic of capitalism was the necessary turn. Adams reflected as much in the 1980s:

“while our struggle has a major social and economic content, the securing of Irish independence is a prerequisite for the advance to a socialist republican society. For now the task is to unite around democratic, republican demands.”

The electoral growth of Sinn Féin also acted to reinforce the sectarian impasse in Northern Ireland. Had the workers’ movement taken up the issue of repression and the prison crisis, and sought to develop a political voice, it too could have won support in these working-class communities. The potential for that is reflected in the fact that even during, and particularly after, the hunger strikes there were trade union strikes over pay which united Catholic and Protestant workers. Notably, civil servants conducted a protracted struggle over pay in 1981, and in 1982 it was the turn of health workers, among the most low-paid section of the working class, who engaged in combative action which was supported by actions of other workers.

Relevance today

Though the capitalist establishment seeks to maintain the illusion, the reality is that the state is not a neutral arbiter that sits above all conflict in society. It is an active participant — acting in the interests of capitalism. This has been displayed clearly in the history of the North, where the British state intervened into the conflict to protect its interests continually, but it is not unique to here.

Across the world, we have seen how “anti-terror” legislation brought in under the guise of protecting civilian lives has been utilised by various capitalist states to clamp down on opposition. In the Spanish state, the conviction of various Twitter users and rappers for “glorifying terrorism”, when they were advocating Catalonian independence, is one such example. In China, security laws have been utilised to smash the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and corral the Uighur Muslim population into modern-day concentration camps. The threat of rocket attacks from Hamas is used by the Israeli state to justify its brutality in the occupation of the West Bank and the blockade of the Gaza Strip, as well as the cruel and dehumanising treatment of Palestenian prisoners.

In all these instances we can learn crucial lessons from the hunger strikes. Throughout the period, the potential for the workers’ movement to challenge the treatment of prisoners and more widely the repressive powers of the state by uniting working-class people was there. Its failure to lead allowed sectarian forces to fill the void. We need to now construct a socialist alternative that takes a clear, independent, working-class position on all these issues and can unite workers in their common interests.