By Robert Ruane

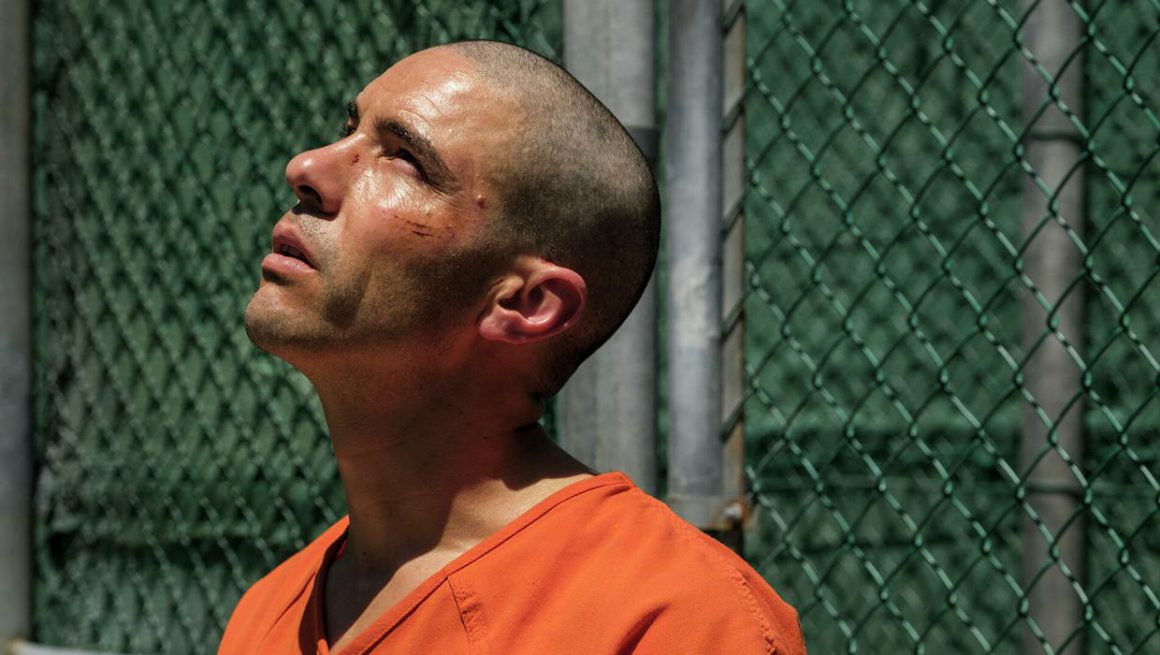

This is the harrowing, inspirational and true story of a prisoner who spent 14 years in Guantánamo Bay without a single charge against him and while experiencing extremely inhuman treatment. The director Kevin Macdonald splits the film into three different journeys; Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s fight for his life (played by Tahar Rahim), Slahi’s defense lawyer Nancy Hollander and her struggle to free him (played by Jodie Foster), and the prosecutor who turns “good guy” (played by Benedict Cumberbatch).

Two months after 9/11, Slahi was effectively kidnapped from a wedding in his homeland of Mauritania by US authorities under suspicion of being one of the organisers of the attacks. While imprisoned in Guantánamo, Mohamedou was tortured for 70 days until he signed a confession. He was chained in the stress position for up to 20 hours with heavy metal blaring in a cold dark room and a strobe light constantly flashing. They also used waterboarding, put salt in his water, deprived him of food and sleep, forced him to have intercourse, even staged a mock execution.

Macdonald does a great job of portraying the hallucinogenic effects of this level of torture. The breaking point came when the interrogators told him that the government had arranged the arrest of his mother, to be transferred to Guantanamo and where, they insisted, she would be raped by other detainees.

Hollander sets out to defend Slahi and habeas corpus, but finds herself constantly running into multiple barriers; the information collected on Mohamedou is classified and the government is withholding the case files. Even when they received the case files from a FOI request, nearly all the data had been redacted. Foster plays the role very well, the neutral professionalism of a lawyer, which gives way to human solidarity and compassion when the details of his torture and innocence are exposed.

Slahi won his case after spending seven years in prison, but the Obama and Biden administration sadistically appealed the decision, which meant he spent another seven in Guantanamo before his eventual release. He never saw his mother again.

Rahim’s performance has been highly praised by critics and it is no wonder. In one scene, we see just how intense and real it is when we observe signs of extreme irritation growing when Nancy asks about why he confessed to financing 9/11 and recruiting the hijackers. He wants to say but fears being heard, and in growing frustration, he bangs the table with his fist. Slahi is thinking about his torture and we know it. He is restless, pacing back and forth and lets Nancy know the frustration he feels: ‘my brother’s and family’s life will go on, yours will go on, but mine won’t because I’m stuck here like a fucking statue!’

Macdonald’s cinematography is also highly effective at showing us just how horrific the whole experience was. The seaside is a clever representation of freedom and in the first scene, Macdonald uses a tracking shot to follow the feet of Slahi as he walks in the water, no music or talking, only the sound of softly breaking waves. This deeply involves the viewers, moving with Slahi and experiencing the beautiful and tranquil scene, which provides a sharp contrast to what is about to unfold. When Nancy and her assistant Teri, and indeed the viewers, first lay eyes on Slahi in prison, the camera is focused again on his feet, only this time they are shackled and there is no moving tracking shot expressing freedom, as the camera is stagnant and imprisoned in the room like Mohamedou.

Macdonald also makes great use of flashbacks and optical points of view so that we see through Slahi’s eyes, such as the scene of his arrival at Guantanamo, there is a bag over our heads as we breathe heavily, panicked. This intensifies the viewer’s experience and helps to emotionally connect us with Mohamedou.

The film arguably engages its viewers more effectively than any other art, and for a moment I was about to respect the real Stuart Couch, who was the prosecutor that resigned from his role after the nature of Slahi’s confession was exposed and after hearing at a church service about respecting the dignity of every human being. I have to criticize the heroic and humane depiction of Couch, however, who later as an immigration judge, told a migrant boy in the court that if he does not stop talking, he will set a dog on him. Also, Couch rejected 92.1% of asylum applications, so much for respecting the dignity of every human being

The film exposed a lot of issues, such as the brutal nature of U.S. imperialism and the capitalist class, the disgusting racism, Islamophobia and deceit behind the so-called ‘War on Terror’. The fact that they kidnapped Slahi without any evidence, imprisoned and tortured him into admitting responsibility, shows that it does not care about justice — as far as the Bush administration was concerned, any Muslim would do as a scapegoat. It is worth noting that terrorists do not form naturally from a puddle in the ground, they are born out of decades of imperialist destruction in their homeland, and for as long as there are capitalist wars, there will be extremism.

Also illustrated in the film, is the toxicity of gingoistic nationalism — the camera focuses on the American flag waving above the barbed wire of Guantanamo, and when Couch is putting on pressure for the release of the MFR’s, he is told ‘either wear the jacket or get off the field’. It also shows us just how perverted, sexist and exploitative the military and the capitalist class are, forcing Slahi to have intercourse with a female guard, using their bodies and sexual humiliation as a method of fabricating a confession. It was revealed that Donald Rumsfeld signed off on these “special measures” of torture.

The Mauritanian is a film that I highly recommend. It demonstrates the immense strength and spirit of one man overcoming some of the most brutal and disgusting oppression. It also reminds us of the urgent and vital need for the working class to destroy the repressive capitalist state and end the imperialist war machine. And although in the end, it attempts to instill a certain level of confidence in the justice system and the state, the fact that Slahi was imprisoned for 14 years without a single charge against him or sufficient evidence, speaks for itself.