By Conor Burke

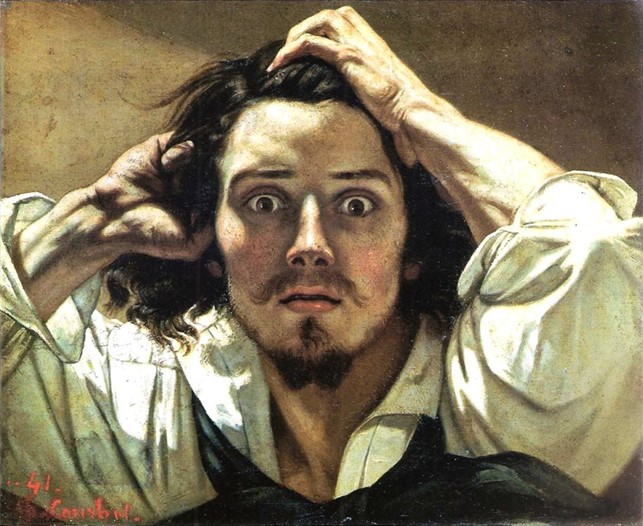

Gustave Courbet Was a French painter from the rural town of Ornans in the east of the country. He is most famous for being the founder of the Realist movement in painting, which is considered by many to be the first modern movement in art. It rejected traditional forms of art, literature, and social organization as outmoded in the wake of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

Although Courbet received some formal training in painting, he was predominantly self-taught and upon moving to Paris at age 21 he spent much of his time visiting the museums and art galleries studying paintings of artists like Caravaggio, Rubens, Rembrandt and Velazquez. At this time, it was normal for aspiring artists to attend an academy where they were schooled in the techniques and traditions of the Arts, but Courbet even at this early stage seemed to defy convention and forged his own path, honing his skills by painting from nature as well as his friends and family.

Breaking tradition

Courbet seemed intent on breaking with tradition, which at that time was exemplified by Romanticism, which focused on an idealised interpretation of the world. Romantic artworks often depicted heroic scenes from history, an emphasis on imagination, spirituality, the exotic, the mysterious, the occult as well as the hero or exceptional figures. Arts and culture up to this point were often a reflection of the interests of the bourgeoisie. Realism set out to challenge that conception and for the first time made scenes from everyday life the central focal point of the work. What’s more is that it often made peasants and the working class the core subject matter, which outraged the more conservative sections of society.

Courbet and the Realist movement wanted to paint what was real, to reject the embellishment of romanticism and to focus on the truth of the world. In 1850, he submitted three paintings to the Salon, which were annual exhibitions of artworks that were selected by the academy system. One of these paintings “A Burial At Ornans” was hugely controversial and catapulted Courbet to fame. Large-scale painting was usually reserved for the depicting of major historical events whereas this was a painting of a normal everyday funeral service of a person with no status within society. Courbet was making the point that the lives of ordinary people are just as important as those of rich aristocrats or famous historical figures.

Radical thinking

Courbet’s work and the focus of his subject matter brought him to the attention of the socialist thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon who influenced Courbet and helped him develop his radical ideas. Courbet, like Proudhon, was in favour of radical democratic reform and modernisation of state and society. He read many revolutionary texts which had a major influence on the development of his painting.

In 1855, he again submitted multiple works to the salon selection committee, and again many of his works were accepted, however a few were not, including one titled “the artist studio” which may have been interpreted as being critical of the salon system itself. Courbet did not take the rejection of his work lying down, and since the salon was not willing to exhibit all of his work he set up his own exhibition. He rented a venue near to the salon and displayed his work in direct competition with the academy. This was a challenge to the dominance of the salons and the academy system but also to the bourgeois domination of culture that was epitomised by the regime of Napoleon III.

Revolutionary times

Courbet’s ideas and political leanings were very much in keeping with the times he lived through, which like himself were both radical and revolutionary. France at this time was deeply divided between a large rural Catholic conservative population and the more radical free thinking working classes in Paris, Marseille, Lyons and other major cities. Courbet was very much involved in the milieu of radical debate and discussion which was reflected in his artwork and within the Realist movement that he spearheaded.

Paris had a long revolutionary tradition stretching back to 1789 which was renewed in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848 and demonstrated again in the resistance to Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup d’état of 2 December 1851. Thereafter, election results and the plebiscite of May 1870 confirmed that Paris remained the centre of opposition to the Second Empire. It was in this context that Napoleon III instigated the Franco-Prussian war to rally a nationalistic fervour and to try and cement his legacy in a similar manner to his uncle (Napoleon I). Unfortunately for him he was defeated and captured by the Prussian forces which advanced into France and surrounded Paris.

This provoked a mobilisation of resistance in the form of the “government of national defence”, and Courbet like many others was keen to play his part, taking up a role as president of Arts commission through which he endeavoured to protect Parisian museums throughout the siege. The government of national defence was led by former regime loyalists and was more concerned with brokering a deal with the Prussian forces than protecting the people and working-class neighbourhoods of Paris. When they attempted to remove the city’s cannons the working class of Paris rose and overthrew the government of national defence and instigated the Paris commune. Courbet saw the Commune as a progressive antidote to the conservative and imperialist society that had preceded it, and as a mechanism to open the arts to the masses in contravention to the elitist academies and salons.

The Artists Federation

Courbet had used his position as president of the arts commission to petition the government of national defence to dismantle the Vendome Column, which was erected by Napoleon I in 1810: it was 44 meters tall and featured a statue of Napoleon at the top. The column was decorated with relief carvings that were made from the melted down cannons of armies that Napoleon had defeated. This monument was seen by Courbet and the communards as a shrine to imperialism and oligarchy, “a monument of barbarism”. Basically, everything that was wrong with bourgeois French society. So, based on Courbet’s suggestion the column was torn down. This would later come back to haunt him.

Courbet was elected to the council of the Commune as a delegate to public instruction and president of the Artists Federation that succeeded the arts commission. The Artists Federation was composed of a variety of artists representing different disciplines. They set about the task of transforming the structures within which artists engaged and democratising the process by doing away with the elitism that existed under bourgeois control. The federation of artists included in its manifesto a specific demand for the equal rights of women artists who had previously been excluded and suppressed from the salon exhibitions.

While technically women were allowed to submit work for selection by the academy, conservative, sexist and chauvinistic attitudes meant that it was very rare that female artists were selected. Including this statement in the manifesto was a direct challenge to these old ideas. They stated as their goal the desire to open up the arts to the general public, they insisted that “everyone had the right to live and work amidst beauty”.

The Artists Federation gave control of the arts to the artist themselves via democratic structures. This was a major shift away from the control and domination of the bourgeois academies and state institutions that held major sway over who and what kind of art was deemed as “appropriate” for public consumption. This would have allowed artists to follow their own inspiration and direction. Such demands no doubt played a significant role in the development of modern art movements that followed on from the commune and the Realist movement.

A profound legacy

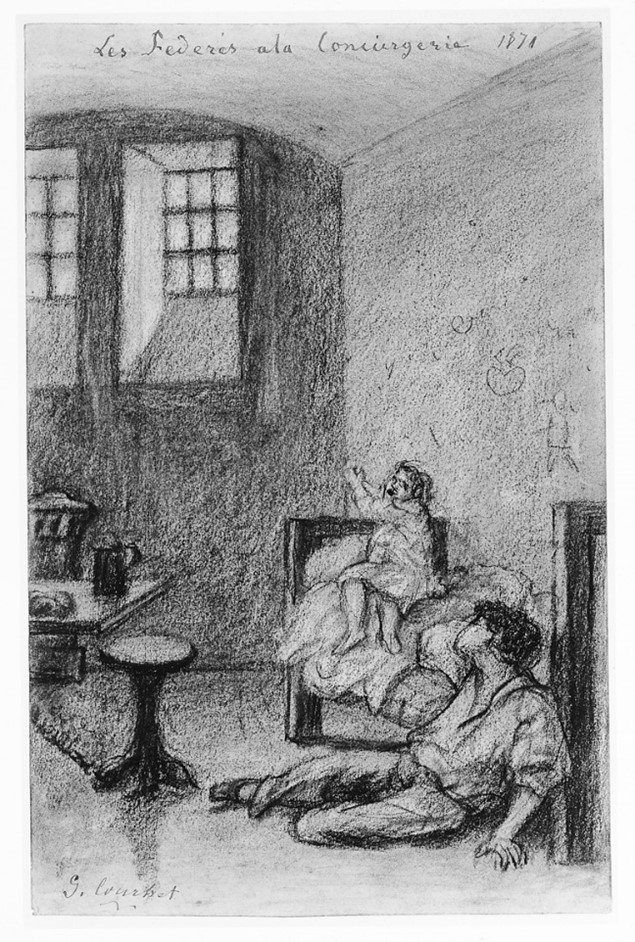

Unfortunately, these ambitions were not to be realised by Courbet and his contemporaries as the Commune was defeated and brutally suppressed in blood and mass incarceration of the Communards, including Courbet who was sentenced to six months in prison for his role in the demolition of the Vendome Column. He was also ordered to pay 323,000 francs for its restoration, which would have left him penniless. He made the decision to flee to Switzerland where he lived out the rest of his years. He died four years later at the age of 58.

We remember Gustav Courbet on this 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune for his revolutionary convictions, and of course for his art that shone a light on the real lives of the working classes, making them the focus at a time when such things were frowned upon by bourgeois society. We also remember the Realist movement in art that sparked the beginning of the modernist period which produced some of the greatest works of art the world has ever seen.