By Thomas Carmichael

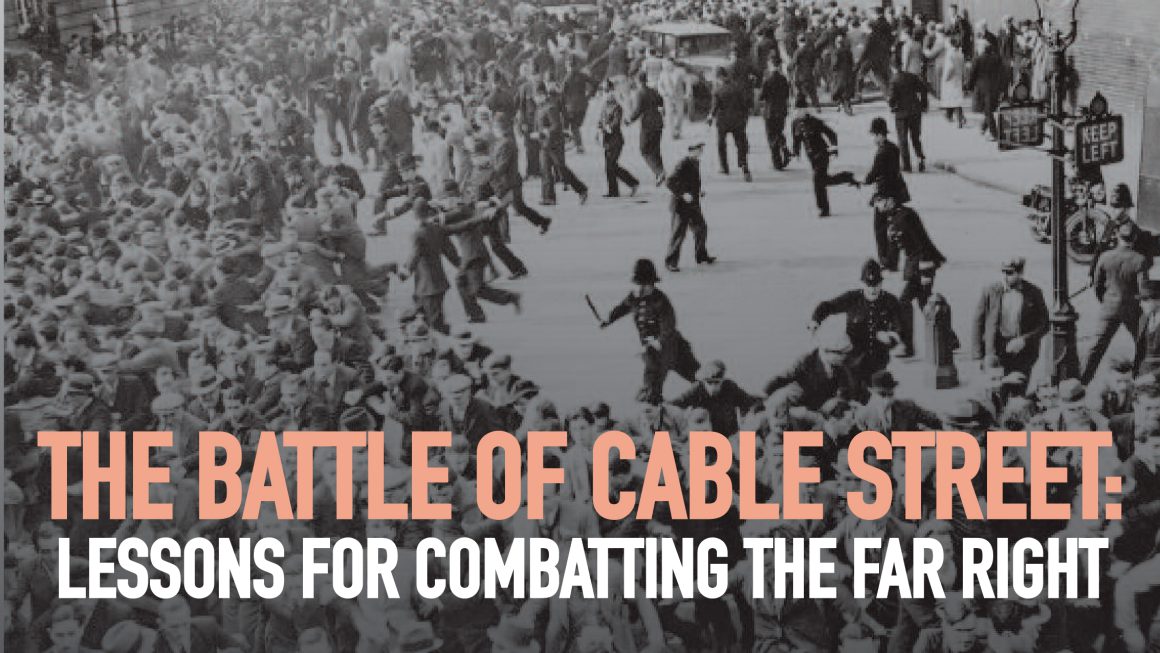

84 years ago today, on 4th October 1936, Communists and socialists came together with Jewish and Irish workers in an historic stand to stop Oswald Mosley and several thousand of his fascist Blackshirts from marching through the East End of London. In what became known as The Battle of Cable Street, Mosley and his thugs, with police protection, were blocked by an estimated 300,000 counter-protesters across east London.

Against a backdrop of a huge economic downturn, the Great Depression of the 1930s, fascism was on the rise across much of Europe. By the time of Cable Street, Hitler was in power in Germany, Mussolini in Italy, and the opening shots of the Spanish Civil War had only recently been fired. Everywhere fascism reared its ugly head, it was met with opposition from the working class. In Britain, Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF) claimed a membership of 50,000 at its height and enjoyed close links with elements of the British ruling class. The Daily Mail on one occasion ran a headline reading “Hurrah for the Blackshirts” and, on another, described the BUF as “Patriotic Angels”. Two members of the BUF would later go on to win parliamentary seats as members of the Conservative Party.

In the weeks leading up to the battle, Mosley and the BUF held a series of meetings across the East End of London, an area with a large Jewish population, with the intent of whipping up antisemitic sentiment among the working class. In particular, they aimed to scapegoat vague notions of “Jewish interests” for a wide variety of societal ills, including the looming threat of war. As a culmination of these meetings, Mosley planned a march of the Blackshirts through the East End in full uniform as a show of strength for his movement and to intimidate the local Jewish population.

Mass community resistance

An outcry from the local community immediately followed, with a petition calling for the march to be banned outright gaining 100,000 signatures. However, the response of many community and political leaders was tepid and completely out of step with the feeling of the mass of the population in the East End. Leading figures in both the Communist Party (CP) – which was a significant political force in east London at the time – and the Labour Party spoke out against the prospect of directly confronting the march, in favour of a peaceful protest against the fascists to take place elsewhere. Jewish leaders organised a sports day out for young people on the day of the march, in an attempt to get them away from the area.

However, these views were in no way reflective of the views of the wider East End community. The Independent Labour Party, the rank and file of the CP and many Jewish groups called for direct confrontation against the fascist procession. Their calls received a huge response and, on the 4th October, an estimated 300,000 people packed the streets of east London. Irish dock workers erected barriers on Cable Street itself to stop the march. The main confrontation took place near Gardiner’s Department store, where 7,000 police officers, including some on horseback, attempted to clear the crowds to allow the march through, but to no avail. The police commissioner called the march off and Mosley, humiliated, was forced into retreat and his organisation went into decline.

Lessons for today: Covid, conspiracy theories and the far right

Today, in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the far right are attempting to find new audiences for their poisonous ideas, as we have seen on both sides of the divide in Northern Ireland, for example. Many ordinary people are understandably frustrated, confused and afraid. This is a product of capitalist governments’ inefficient, contradictory, pro-corporate and sometimes draconian responses to the crisis. This – as well as the absence of mass left forces and a fighting workers movement, compared to the 1930s – has allowed conspiracy theories to gain traction, theories which misinform and misdirect people’s legitimate anger.

Significant anti-mask, anti-lockdown protests have been held in countries across the world, including in Ireland. Some of these protests have been initiated by far-right organisations or have had significant far-right presences, with instances of fascist thugs attacking left-wing activists, including in Dublin. These groups are generally not putting forward their full racist and reactionary programme to others taking part in these protests. Regardless, the emboldening of the far right and the potential for them to broaden their support is a very worrying development.

The key lesson to be learnt from the Battle of Cable Street is how crucially important the building of broad support in the community is. The success of the anti-fascists came from the drawing together of broad layers of the working class – not only the Jewish community, who were the direct target of attacks by the BUF, but also Irish workers and others standing in solidarity alongside them. This kind of broad support cannot be built by anti-fascist work alone, but by engaging with the working class on all the issues that face them day and daily, issues like job losses, poverty, housing and cuts to public services.

This lesson could not be more relevant to Northern Ireland today. With far-right groups attempting to build in both communities’, anti-fascist campaigning must be cross-community and completely anti-sectarian if it is to be successful. In this regard, the trade union movement – representing almost 250,000 workers from across the sectarian divide – should be central to mobilising against fascist groups, as well as stewarding and organising these mobilisations. But this must be linked to developing a programme and a campaigning approach – based on the industrial power of workers – which can provide a positive, political alternative to the far right and conspiracy theorists.

Physical confrontation and counter-protest: tactics, not principles

While direct counter-protest and physical confrontation was clearly the correct tactic in the case of Mosley in 1936, it is important to remember that it is not the only tactic available in anti-fascist work and may not always be the correct one. When Mosley attempted to march through the East End, it was with 3,000 fascist thugs at his back – with the total membership of his organisation being more than ten times this number – and against a backdrop of fascism on the march on a global scale. But the workers’ movement could also be confident of its ability to greatly outnumber and defeat the fascists when a clear call was made.

Today’s far right, though noisy and certainly active, is nowhere near as widespread or as powerful as the fascist groups of the 1930s, at least in most countries. On the other hand, the workers’ movement and the left also does not have the same authority and weight in society as that shown at Cable Street. It is also important to remember that not everyone sympathetic to the anti-mask movement, even to the point of actively engaging with it, is far-right or fascistic themselves. The support enjoyed by the movement and by conspiratorial ideas in general is born out of disillusionment with capitalism and with establishment political parties and the mainstream media.

In the absence of a fighting trade union movement and a left force with a mass base in society, some of those looking for answers to society’s problems can encounter and become influenced by conspiracy theories and even the ideas of the far right. If individuals in the early stages of this ‘pipeline’ to the far-right attend an anti-mask protest out of the earnest but mistaken fear that it’s all a ‘plandemic’ designed to strip away their democratic rights and enrich the wealthy elites (again, a misdiagnosis of a very real problem: capitalism) and are met with a counter-protest loudly denouncing them as ‘Nazi scum’, it could have the effect of making them feel victimised and persecuted for asking questions, and actually entrench them in their newfound views, speeding up the ‘pipeline’ process. A more effective approach can be for the left and the workers’ movement to take separate and independent initiatives around the real issues concerning ordinary people, while also countering the lies of the far right. The tactics used to tackle far right groups need to be based upon an assessment of the balance of forces, of consciousness, of how these groups are regarded by different layers of the working class and so on.

Building a strong left is key response

The real and long-term solution to the growth of the far right is the building of a strong left with broad support that takes up the issues that are faced by the working class in a way that cuts across the far-right’s narrative. It is absolutely crucial to realise that conspiratorial and reactionary mindsets are born out of the disenfranchisement that is bred by the failures of capitalism. We need to ensure that, when working-class people go looking for answers to their problems, they find coherent answers from a strong, organised and militant working-class movement and left – one that is ready, willing and able to back up its words with the building of campaigns to effect real and lasting change, and bring about a socialist alternative to the misery of capitalism. That will ensure that, when fascism rears its ugly head, it can be effectively challenged, as at Cable Street.