By Ben Samson

The word ‘crisis’ has by now become synonymous with the year 2020. It has been punctuated by highly broadcasted events such as the the US drone-killing of a top Iranian general, the apocalyptic Australian bushfires, the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, intensified trade wars between the US and China, an unprecedented economic crash, and explosive uprisings against police brutality and systemic racism across the US and elsewhere.

However, other than the possibility of nuclear conflict that could arise from inter-imperialist skirmishes, climate change remains as the gravest of all crises that continues to develop in the current period. As reported in a study published in May of this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a “business-as-usual” climate scenario will result in one third of the global population living in regions which will no longer be able to sustain organised human life.

Overconsumption – the wealthy do it best.

Published in June of this year in the prestigious scientific journal, Nature Communications, was a perspectives article in which evidence is presented which points to affluence rather than consumption as being the main driver of climate change and environmental destruction. Unsurprisingly, it was reported that “the world’s top 10% of income earners are responsible for between 25 and 43% of environmental impact”, whereas “the world’s bottom 10% [of] income earners exert only around 3–5% of environmental impact”.

Lifestylism versus systemic change

While the authors criticise the aspect of capitalism that requires endless economic growth using a finite amount of resources, they also, correctly, do not prescribe “degrowth” to developing economies in the global south, nor do they recommend that this is desirable in the global north should it prevent much-needed investment in core infrastructure, essential services and that production which is necessary to combat poverty in disadvantaged areas.

Of equal importance, it is made clear the futility of simply relying on the adoption of “sufficiency-orientated lifestyles” to address climate change. Globally, we know that 100 companies are responsible for 71% of all emissions. Capitalists will tell us that this is the result of poor decision making when it comes to working class people consuming things. However, the authors make it clear that there are numerous barriers to the individualist strategy of simply consuming in a more conscientious way, such as inadequate housing, low income, poor options for socialising, employment and transport, as well as a “high exposure to consumer temptations”.

This flies in the face of an out-of-touch capitalist class who simplistically argue that green consumption is all that is needed. There is much truth to the adage which says that ‘there is no ethical consumption under capitalism’ as it is generally impossible to buy a product for which some form of exploitation did not occur at any point during its development. The authors go on to invoke the outlooks of Marxism and environmental sociology, which say that supply drives consumption, rather than the other way around. In this sense, resource availability influences what capitalists produce, with marketing and advertising doing the job of manufacturing a demand for this produce.

The authors lay bare how the super-affluent – as opposed to workers – are almost exclusively responsible for climate breakdown. Not only do their opulent lifestyles mean that, individually, they by far and away consume the most, but they also set consumption norms across the globe and tend to be “members of powerful factions of the capitalist class” (thereby allowing them to purchase political power).

Averting climate breakdown impossible under capitalism

Although the lifestyles of rich people are certainly damaging, the authors do not conclude that the affluent 1% should simply adjust their consumption. In addition, both “green-growth” and even economically reformist approaches are criticised as possible solutions because they do not go far enough. The inherent difficulties of making significant advances in the fight for climate justice under capitalism are spelled out in impressive detail.

On the production end, the constant efforts of capitalists to remain competitive means that they will always seek to maximise profits by constantly ramping up the “energy intensity of labour”, which is now twice as high as it was in 1950. On the consumption end, the super wealthy are compelled to “positionally consume” as they neurotically outspend one another to signify a dominant social status. At the bottom, workers are forced to compete against each other to sell their labour, which means they must routinely equip themselves with new capitalist goods (smart phones, cars, kitchen appliances etc.), a process which the authors term “efficiency consumption”.

Not only are the “underlying forces of overconsumption” unlikely to be addressed within the framework of a global capitalist economy, but even moderate reforms will not be tolerated by the capitalist class. Should a social democratic government threaten to increase tax on high earners and multinational corporations in an effort to fund green infrastructure, they will simply threaten to relocate to a different region. While radical economic policies are popular electorally, particularly among young people, capitalist media often fronts a fierce resistance to political groups that are even moderately reformist, meaning that an exclusive focus on parliamentary politics will not provide the badly needed change fast enough.

In the end, the authors proffer “eco-socialism” and “eco-anarchism” as the most credible approaches to achieving the necessary economic transformation to combat climate change. Although both challenge capitalism as an economic and social system, relying on grassroots movements and participatory democracy to bring about serious change, the latter does not see electoral politics or state power as fundamental aspects of the struggle to achieving the necessary socialist solution, which is clearly mistaken.

Climate justice – what is to be done?

As Marxists, we agree that capitalism is the root cause of climate breakdown as well as multiple forms of oppression and crises, ranging from worker exploitation, racism, women’s and LGBTQ+ oppression, imperialist wars, to the present Covid-19 pandemic and historic levels of inequality. Critically, if catastrophic climate breakdown is to be prevented, the various forms of exploitation and oppression that affect working-class people and which are inherent under capitalism must be combatted.

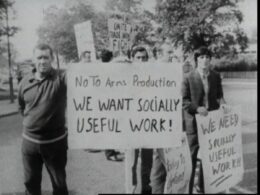

This means fighting for socialism on every front, building movements of class-conscious workers and young people that are ready to strike at the core of the horribly outdated capitalist system – replacing market anarchy with a planned economy. Nothing less will do.