By Keely Mullen, Socialist Alternative USA

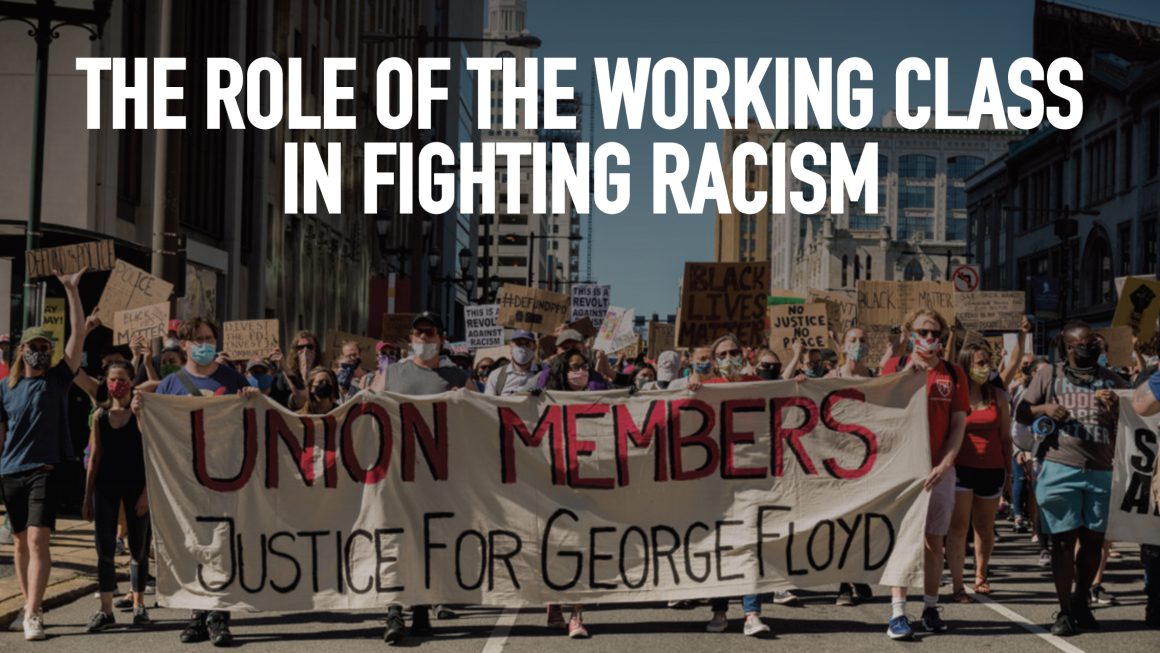

Two nights after George Floyd was murdered, Minneapolis bus drivers received an urgent request for a fleet of buses at the corner of 26th Street and Hiawatha Avenue in South Minneapolis. The request came from the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) who were gearing up for mass arrests at a Black Lives Matter protest and intended to use the buses to transport protestors to jail.

The leadership of the Minneapolis bus drivers’ union, Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 1005, refused. They urgently declared their support for protestors and refused to be used by police as a bludgeon against the movement. The next night, New York City bus drivers followed suit.

The action taken by these drivers went viral. It was picked up by major news outlets and made its way onto the social media feeds of millions of Americans. In the context of a labor movement that for decades has limped behind social movements, this act of working-class solidarity was a sign of what’s possible.

Solidarity with BLM

The action taken by Minneapolis bus drivers kicked off a limited but important wave of labor solidarity with the #JusticeForGeorgeFloyd movement. In Minneapolis, union postal workers organized a solidarity rally outside of a burned down post office with the main slogan “you can rebuild a post office, but not a life.” (See page 7 for more).

On Juneteenth (June 19), which commemorates the end of slavery in the U.S., actions were taken by some major unions. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), a union with a long record of supporting social movements, shut down ports along the west coast in solidarity with protestors. The United Auto Workers (UAW) urged their members to organize nine-minute slow downs symbolic of the nine minutes police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck before killing him.

While these actions are important, they’re rather isolated and are not connected to an overall strategy among labor leaders to fight racism. The AFL-CIO hosted a virtual panel after the movement broke out with several key union leaders who all issued lifeless statements that, indeed, racism is real and yes it is bad and people should vote in November. Considering the ranks of unions in the U.S. are now more racially diverse than ever before, this lackadaisical approach amounts to a complete abandonment of their own members.

In 1981, Black, Latino, and Asian workers made up 15-16% of total workers in the production, transportation, material moving, and service industries. Today, in each of those categories, the number is 40%. In the building trades, workers of color now make up 37% of the total workforce compared to 15-16% in 1981.

The multiracial working class is now facing mass layoffs, cuts to social services, rent that’s too high, and wages that are too low — attacks that will disproportionately devastate Black and Latino workers. All of this is an attempt by the ruling class to make us pay for an economic crisis they themselves created.

Fighting for our jobs, our schools, and adequate health care will require a working-class movement that is united across racial lines. The working class derives its social power from its ability to shut down the profits of the capitalists by refusing to work. Harnessing this power to its full extent requires the broadest possible participation of working people, something that is impossible if we are divided by race.

Building a united movement does not mean that the demands of Black and Latino workers should be subsumed into the most basic economic demands. It means the broader working class needs to take up the demands of Black and Latino workers. Building the unity needed to win the battles ahead will require the building of a labor movement committed to fighting for overarching economic demands alongside demands against racist policing, segregationist policies in housing and education, and against white supremacist and vigilante violence against communities of color.

We need to build a labor movement committed to overcoming the divide-and-conquer mentality of the ruling class which has used racism for centuries to keep workers fighting among ourselves.

The Color Line

Racism affects Black people in America most consistently, sharply, and with life-or-death consequences. However, racism also directly harms every single working person regardless of race by keeping us divided and prevents us from uniting against society’s real oppressors: the wealthy elite. This division has played an important role historically in preventing workers in the U.S. from achieving many of the gains achieved by workers in other countries including developing our own mass political party or universal health care.

Racism has been used for centuries as a central weapon by the ruling class to assert its dominance. The U.S. ruling class has also used imperialism to build support for their rule in sections of the population. As the most powerful ruling class in the world over the past century, they have successfully used divide-and-rule tactics, strategic concessions, and brutal force to keep the working class from directly challenging their control over society. But they are in decline and some of their old tricks, like crude racism, may not work the way they used to.

The North American ruling class realized early on that the greatest threat to their system was the unity of Blacks and whites who had more in common with one another than either did with the wealthy elite.

In the 1600s, hundreds of thousands of impoverished British and German people arrived in North American colonies as indentured servants. Alongside them was a steady arrival of African people purchased from slave traders who were integrated into the large pool of indentured servants.

In the fields, Black and white indentured servants worked together. They were dehumanized across the board and were all regarded as “filth and scum” by plantation owners. Their shared misery led to a natural sense of class solidarity.

This would change dramatically following what became known as “Bacon’s Rebellion” in 1676 in Virginia. In this uprising against the planter elite, Black and white indentured servants stood together arm in arm. They were brutally slaughtered and the rebellion was crushed. Though overall a victory for the aristocratic landowners, they were terrified by the unity they saw between Black and white servants.

In reaction to this, and to prevent further rebellions, the ruling class set about consciously dividing Black from white. The legal position of white indentured servants was improved. Whipping white servants was forbidden and when the period of indenture finished, whites were provided with “corn, money, a gun, clothing, and fifty acres of land.” Meanwhile, Black indentured servants lost all of their rights. Indentured labor became lifetime, “chattel” slavery.

The American ruling class’ use of racism to divide workers and continue their steady stream of profit has transformed and morphed throughout history.

After the Civil War, the revolutionary Reconstruction period in the South, when poor whites and ex-slaves began to collaborate, ended in a bloody counterrevolution with the unleashing of white supremacist violence by the planter aristocracy. This opened the door to what became known as Jim Crow, a system of racial subjugation based on outright white supremacy comparable to Apartheid South Africa.

Through all subsequent phases of American history, the division of white and Black workers from one another was consciously maintained. Whether it be denying Black people basic legal or civil rights under Jim Crow, waging a culture war to depict Black people as dangerous or violent to justify mass incarceration policies in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, or the ongoing segregation of housing and education — racism and American capitalism cannot be separated from one another.

This is precisely because the ruling class recognizes that at the end of the day working-class whites have more in common, despite all the differences, with working-class Black people than either do with the wealthy elite of any color. Despite all the rhetoric we hear today from many corporations “standing with” BLM, they know full well how profitable structural racism has been and they have no intention of paying the price required to end it. While the bosses generally do not see the need today to resort to the crude divide-and-rule tactics of the past which would not work, now the corporate media cynically encourages a toxic form of identity politics in an attempt to maintain the idea that working people of different races have nothing in common with one another.

The Multiracial Working Class vs. Capitalism

Capitalism in the U.S. has been exposed as a bankrupt system incapable of providing a decent life to millions of ordinary people. It is in the best interest of every single working-class person to build a mighty struggle to take on and end corporate rule. However, American capitalism and racism are so thoroughly intertwined that there is no way to defeat one without taking on the other.

It is possible to win limited anti-racist reforms absent a full scale revolt against capitalism as we’re seeing play out through the current Black Lives Matter rebellion where certain concessions are being made. However, even significantly reducing the funding of the police, a demand which we wholeheartedly support, would not in and of itself address institutional racism.

It would not change the fact that it would take a typical Black family over 52 million years to reach the wealth currently held by the Walton family, owners of Walmart. It would not change the fact that the Forbes 400 richest Americans own more wealth than all Black households plus a quarter of Latino households. Or that majority-white public schools receive on average $773 more dollars per student than majority-Black schools.

The multiracial working class has a crucial role to play in the ongoing fight against racism in the U.S. and we need a labor movement comprised of unions that do more than issue sympathetic statements.

Unions are the central organizations of the working class because they allow us to act as a cohesive unit in the workplace where we have the power to shut down profits.

However, following decades of union leaders preferring backroom negotiations with the bosses to real class struggle, many working people today do not look seriously toward the unions as a vehicle for social change. If we are going to build a working-class fightback capable of taking on the diseased capitalist order, we will need a transformation of the labor movement.

This needs to include mass organizing campaigns in non-union workplaces like warehouses, call centers, the service industry, and the gig economy. It will need to include the democratization of existing unions to allow for real debate and discussion. It will also mean ending the unions’ political practice of writing blank checks to Democratic Party politicians, a practice that has hamstrung the movement for decades.

Achieving this transformation will mean multiracial slates of worker activists contending for the leadership of existing unions. In other cases it may mean the creation of new unions. It will require a rank-and-file rebellion to overtake unions as a central tool for our class in the ongoing battle against exploitation and oppression. If we are able to transform the labor movement into a force committed to uniting the working class in the fight against the bosses and billionaires, we could begin the project of taking down capitalism and building a new world that does not require racism, sexism, or oppression of any form.

The CIO and Black Workers

One of the most dramatic leaps forward in the living standards of Black workers in the U.S. happened through the development of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the 1930s and ‘40s. The leadership of the labor federation from which the CIO was born (and later expelled), the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which based itself on the more privileged craft workers and largely excluded “unskilled” workers, had a rotten record of enabling racism within affiliated unions.

In the run-up to the 1935 AFL Convention there were multiple attempts made by a section of both Black and white union leaders to transform the racial policies of the AFL. However, these attempts were largely swatted away or dramatically watered down. This confirmed for many Black workers that the AFL could not be transformed into a vehicle that would advance their needs.

The refusal of AFL leaders to champion even the most modest demands of Black workers coincided with their unwillingness to alter their structures to accommodate industrial unions which could be home to millions of workers in mass-production industries. Unlike the conservative craft unionism of the AFL, industrial unionism advocates organizing everyone who works for one employer into the same union. The AFL’s stubborn opposition to industrial unionism led to a revolt that coincided with the realization by many that the AFL leadership was content to sit on their hands in the face of racism within the labor movement.

This, in many ways, created a perfect storm and out of the 1935 AFL Convention, where the leadership’s conservatism was exposed across the board, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was born.

Soon after its founding, the CIO embarked on one of the largest scale organizing campaigns in American labor history. They targeted a number of key mass-production industries such as steel, auto, rubber, and meatpacking. A central tenet of organizing these industries was winning over thousands of Black workers whose experience of the labor movement was not positive. Organizing mass, multiracial industrial unions meant not only convincing Black workers that the new American labor movement would not bear the marks of the conservatism of the AFL. It also meant convincing white workers that the only way they could advance their own interests was by fighting alongside Black workers.

Organizing Steelworkers in 1936

The first test for the CIO came in the dramatic battle to organize steelworkers across the U.S. in 1936. After taking over the Association of Iron and Steel and Tin Workers, the CIO established the Steel Workers’ Organizing Committee (SWOC) which was tasked with rallying the more than 500,000 steel workers across Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, and Alabama.

There were 85,000 Black workers in the steel industry, 20% of the total workforce. They occupied the worst possible position within the mills and were paid between $16 and $22 a week, far less than their white counterparts. In an attempt to buy the loyalty of Black workers, the steel industry poured money into Black churches and fraternal societies. They were confident this investment would pay dividends as the SWOC began their organizing campaign.

However, what the steel barons did not account for was the determination of CIO leaders or the position of the National Negro Congress (NNC) which was determined to write a new chapter for Black workers.

The NNC, with deep ties to the Communist Party, was formed in 1935 with the goal of fighting racism in the context of the Great Depression. In early 1936, John P. Davis, co-founder of the NNC, said of the SWOC campaign:

“There is no effort in which the National Negro Congress could possibly engage at this time more helpful to large numbers of Negro workers… than the organization of negro steel workers… 85,000 negro steel workers with union cards will signal the beginning of the organization of all negro workers.”

The NNC did far more than issue statements of support to the steel workers’ organizing campaign. At a national level, they recommended dozens of Black organizers to be hired by the union and sent to key steel towns to build support for the organizing drive. On top of this, wherever there were local councils of the NNC, they contributed volunteer organizers to build the campaign deep in the Black community. They approached Black churches, clubs, and organizations encouraging them to sponsor mass meetings to recruit Black workers into the union. A typical NNC leaflet read: “we colored workers must join hands with our white brothers… to establish an organization… which shall deliver us from the clutches of the steel barons. We appeal to all colored workers in the steel mills to join the union.”

By the end of 1937, the SWOC represented the entire steel workforce including the 85,000 Black workers who at that stage constituted the largest group of Black union workers in the U.S. After a year of determined organizing by Black and white workers, wages were raised by one-third, working hours were reduced, and certain Jim Crow practices were ended in the steel industry. While conditions remained very difficult in the industry, the situation had dramatically improved.

By 1940, 200,000 Black workers had joined the ranks of the CIO. However, this forward march could have gone further. In 1945, the CIO launched “Operation Dixie” to organize key Southern industries. To win this campaign would have required a decisive battle against Jim Crow itself whose racist laws were meant, among other things, to keep unions and radical organizers out of the South. The campaign ended in failure because of an insufficiently bold approach, which contributed to eroding the strength of the unions in the North over time. If Operation Dixie had triumphed it would have opened a new and possibly much more decisive phase in the class struggle in the U.S. But what was once again confirmed, this time in a negative way, is that the advance of the labor movement requires a fight against racism as a central strategic task.