By Ruth Coppinger

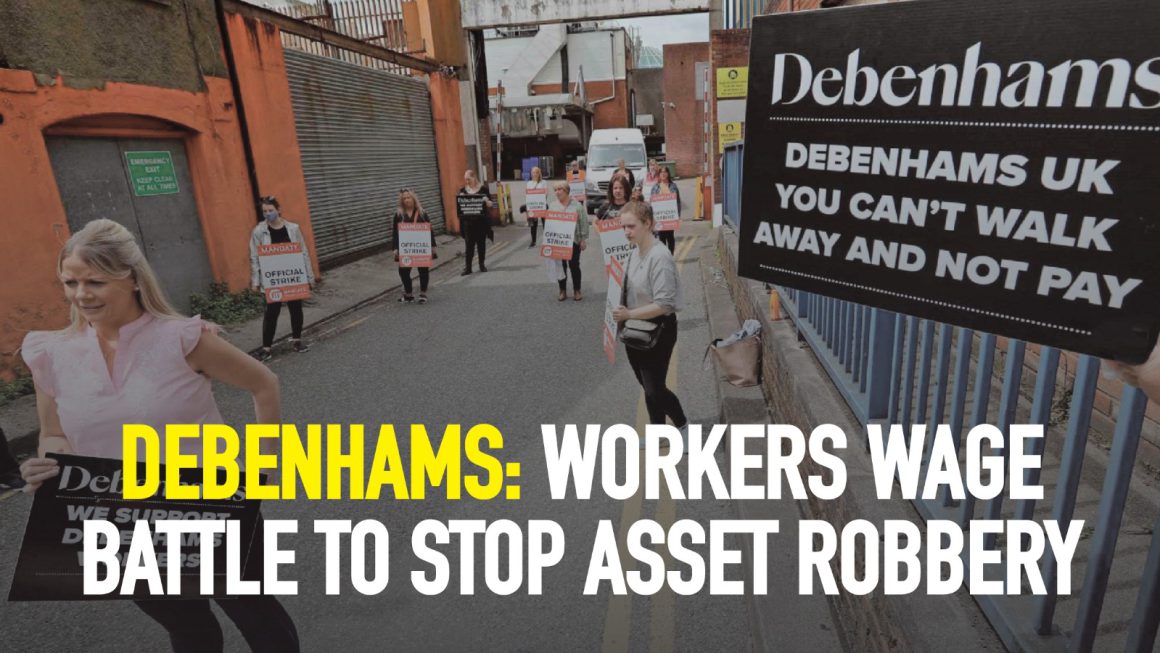

Since being laid off in April, Debenhams workers have waged a David and Goliath battle to save their jobs or win a redundancy package befitting their years of service.

Pitted against a big multinational chain, the Irish workers deserve massive credit for remaining a thorn in the side of this company, who coldly used a pandemic to dump up to 2,000 workers.

Despite pandemic restrictions, the workers have publicised their case, safely and successfully staging protests at shops, at Bank of Ireland branches nationwide ( BOI has stake in the company) and at the Dáil throughout May.

Resounding vote for action

In a ballot, a resounding 97% voted in favour of industrial action to prevent valuable stock and assets being removed from stores by UK-based parent company, Debenhams Retail Limited (DRL). In a repeat of what happened at Clerys in 2015, when the owners of Clerys were able to shift everything profitable into a separate company, DRL claimed ownership of all assets — stock, leases and online trade — leaving the Irish subsidiary saddled with the debts. This is despite the fact that online profits previously accrued to the Irish business.

Such manoeuvres allow companies avoid paying severance packages for workers with long service, and leave the Irish taxpayer to pick up the tab for minimum statutory redundancy. Not only do workers suffer losing their jobs and the trauma and uncertainty that goes with that, but they’re effectively robbed — years of labour they’ve put in is stolen in reduced redundancy.

Clerys Mark two

This is a feature of capitalism in recent years, taking more and more of what’s called the social wage, undermining or blatantly raiding pension schemes and often consigning workers to poverty in old age. It ties in with the accumulation of wealth more and more to the top of society and less and less at the bottom.

Bills that were moved four years ago to prevent a Clerys Mark two were never progressed in the Dail.

There is a lot of inter-generational employment at Debenhams: grandmothers, mothers, daughters working there. But that sense of belonging and loyalty means nothing to shareholders. Workers again got a generic letter from the liquidator and will simply get an appointment to come and collect their belongings after years of service.

In the Debenhams struggle, we are seeing laid bare that the laws and machinery of the state are set up in the interests of big business, not workers. Everything from the liquidation hearing in the court where they had no voice, to the perfunctory way the liquidators ticked boxes and sanctioned the liquidation

And the 30 day ‘consultation’ period proved useless to the workers. Legitimate questions from their union Mandate weren’t adequately answered.

The role of liquidator

Myself, Mick Barry TD and a Debenhams worker held a meeting with the liquidator. The ownership of stock is still being contested, but the liquidation was still allowed go ahead with no extension.

Another lesson has been how little interest there is on the part of authorities to ascertain the real financial situation of companies closing down. Workers’ demand for the books to be opened up is never granted.

One Debenhams worker did huge research and continually mailed the liquidators, challenging figures put out by Debenhams. She was able to piece together her own accounts, which, amongst other things, showed the situation wasn’t as dire as depicted:

Debenhams Ireland say business was not viable, but the annual turnover for the years 2016-2018 was actually higher than 2011- 2015. There were 1803 employees in 2010 and only 1373 in 2018, so pension contributions and payroll costs would have been considerably less.

The company’s most recent audited accounts for the financial year ending 1/9/18 show a pre tax loss of €20.6 million — but this included exceptional items/costs of €18.8 million, which means the actual loss was €1.8 million.

Seventeen percent of sales were online in 2018, equating to €28.7 million. The High Court was told on two occasions that the online business was owned by the Irish company. Yet the online business has since been swiped by the UK parent company. The lucrative online business is worth even more now with no Debenhams stores in Ireland.

The workers have battled to bring out these figures and to show that with rent reduction and other measures, debts could be overcome — but neither the liquidator or anyone in government has shown an interest.

Unfortunately, the Irish Congress of Trade Unions has remained absolutely silent throughout, despite Debenhams being a large unionised workforce and a test case for the retail sector and entire workforce.

A determined struggle

The resilience of workers in the face of obstacles is really remarkable. In Cork, workers put on a flash picket when they discovered cash was being removed from the Patrick Street store. Since then, they and other stores have had a workers’ watch on loading bay areas. Any attempts to move stock in these stores will result in a picket.

In Henry Street, workers decided to place an official picket on the store last Saturday. Once again, Gardai harassed and moved the picket from the front of the store and confined it to the loading bay. The workers intend to go to the Dail to highlight that their constitutional right to strike is being denied.

Workers in other stores are now discussing using the ballot for action to put pickets on stores and totally block any stock movement. This would leverage to extract a deal by frustrating attempts by Debenhams to move on. Interrupting the efforts of Debenhams to trade in the UK and the north is also being considered by the union.

State intervention

Meanwhile, the Irish political establishment has sat by and allowed this jobs massacre. While some members of Fianna Fáil and the Greens stopped by to pose for pics, the saving of jobs hasn’t formed part of their Programme for Government. At least three stores are confirmed to be profitable — Blanchardstown, Newbridge and Mahon Point but others would be with rent reductions. For example, Debenhams in Warrington in England is reopening following a rent cut brokered by the local council. No efforts were made by the government to lift up the phone to the liquidator or to Debenhams to discuss the situation in Ireland.

In the view of the Socialist Party, the state should step in to take over Debenhams — and other sectors where jobs are threatened. Run under public, democratic control, with a business plan and with workers at the heart of running the company, stores could reopen and the fruits of online trade would also be used to invest. The state is currently propping up private industry massively. Why should a retail company not be publicly owned?