by Kevin Henry

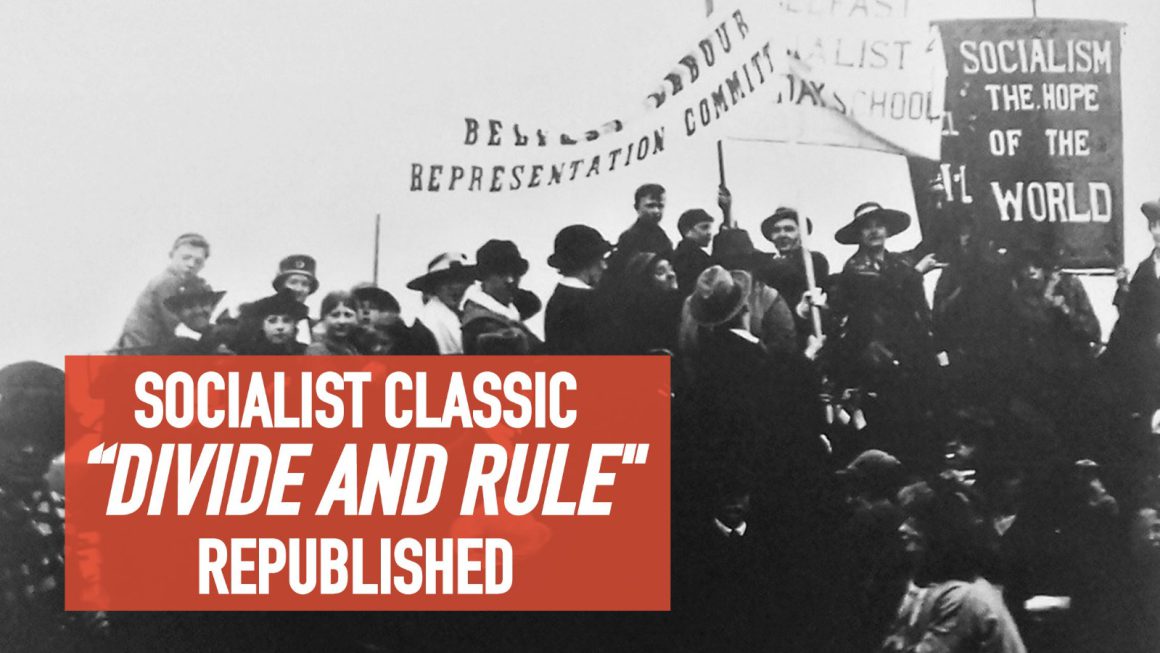

Today, 5 May 2020, marks the 10th anniversary of the death of Peter Hadden, a Marxist thinker and leader of the Socialist Party in Ireland, and of our International. In particular, Peter played a pivotal role in developing a Marxist understanding of the national question, not just in Ireland, but for socialists grappling with similar problems worldwide. This year, the Socialist Party intends to re-print some of Peter Hadden’s key works, which we think will be an assist for a new generation looking towards socialist ideas as an alternative to sectarian division. Our first re-print will be of Divide and Rule, written in 1980, in which Peter analyses the period leading up to the partition of Ireland. Below is the introduction to the new edition.

Written by Peter Hadden forty years ago, Divide and Rule is a Marxist classic. The book’s key argument is summed up in the first line: “The partition of Ireland was a conscious act on the part of British imperialism chiefly intended to divide the working class along sectarian lines.” Fifteen years later, in Troubled Times, which the Socialist Party also intends to reprint this year, Peter Hadden said that Divide and Rule was written “mainly as a challenge to the simplified, romanticised picture painted by nationalists.” But it was also a challenge to Unionist historians and to the revisionist school of Irish history which had been in the ascendent from the early 1970s onwards. What all these schools of history have in common is that they ignore the class interests and forces which have shaped the course of Irish history.

In that regard, Peter Hadden’s work stands in the tradition of those Marxists who studied the history of Ireland using a class analysis, including James Connolly, as particularly reflected in his books The Reconquest of Ireland and Labour in Irish History. These writings recognise the centrality of class division in Irish history, how the interests of both the British and Irish ruling classes shaped their actions.

This book also affirms Connolly’s well-known and prophetic warning that partition would mean “a carnival of reaction both North and South”. What is less commonly referenced is Connolly’s logic as to why this would be the case – that it “would set back the wheels of progress, would destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish Labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements whilst it endured.” Crucially, however, Divide and Rule also affirms that “Labour and working-class unity were the real victims of partition. Labour alone could have averted this menace.”

This idea reflects a key hallmark of the approach of Peter Hadden and the Socialist Party to the national question in Ireland, which combines a sober assessment of the balance of forces, and a preparedness to raise sharp warnings about the dangers of sectarianism, with an ultimately optimistic perspective about the capacity of the working class to transcend sectarian division. Today, that is reflected in our slogan, “For workers’ unity and socialism.” The same optimism is found in Divide and Rule. In the introduction, Peter Hadden makes this vital point which runs like a thread through the rest of the book:

“The tactic of “divide and rule”, of setting Catholic against Protestant, has again and again been used in Ireland. But history shows, not once but repeatedly, that the oppressed masses are capable of overcoming religious divisions and withstanding the attempts of the exploiters to set them apart. Unity of the oppressed has always been possible on the basis of opposition to oppression.”

Leadership matters

Another important theme is the crucial role which leadership plays in the labour movement. Essentially, this approach is criticised by other historians, including those on the socialist left.

For example, Conor Kostick in his very informative book Revolution in Ireland and in other publications criticises Divide and Rule for exaggerating the import of what is described as the “criminal” decision of the labour movement not to stand in the 1918 general election. Peter Hadden argues that the policy of ‘labour must wait’ conceded leadership of the anti-imperialist struggle to sectarian, nationalist forces. For Kostick, it was “a missed opportunity to raise the distinct interests of the working class but it was not the kind of defeat – such as that of 1913 – that damages the fundamental structure of the working class movement.” Instead, Kostick argues that “the real turning points of the period were not electoral ones but the outcomes of the incredibly radical mass movements of workers against opponents ranging from the British authorities to Irish employers and landowners.”

However, these are linked. The lack of a revolutionary leadership with confidence in the capacity of the working class to take matters into their own hands had an important effect on countless struggles that did develop. As Peter Hadden argues here and the Socialist Party stresses in other publications, the period was one of revolutionary struggle, not just internationally but also in Ireland, including united struggles of the working class of the North, most notably the 1919 Belfast engineering strike. It is this movement of working people that could have transformed the situation if armed with a socialist perspective and programme. As Peter Hadden put it:

“North and South one united class movement was developing during this period. What was required was a leadership which could tie together, in the minds of all the workers, the land and factory seizures in the South, the takeovers of towns such as Limerick, with the industrial muscle revealed by the Belfast working class in 1919. A common struggle against capitalist domination could have been begun.”

This would have required developing a programme which would take up all the democratic demands and link them with the need for socialist change and for decisive action on the part of the workers’ organisations, so that the labour movement would clearly articulate the need:

“Not just for a republic, but for a workers’ republic! Not just the right to have a parliament but for a revolutionary constituent assembly which could take the factories and the land out of the hands of the speculators and profiteers and place them in the hands of the working class! Not just for rule by the “Irish people” but for rule by the Irish workers, the only class capable of solving the problems of the small farmers and all the middle strata of society. Not just for independence, but for independence from British capitalism! Not just for freedom, but for freedom from exploitation! Not just against national oppression, but for socialist internationalism including the forging of the strongest possible links with the organizations of the British working class!”

While united class struggle was developing on the industrial plane, the decision by the Labour leadership to stand aside from the 1918 general election meant this was not given national expression on the political plane at a crucial juncture. Only in Belfast did Labour field candidates. The opportunity to tie together the struggles of workers North and South was squandered. The fact that Labour broadly stood aside to make way for Sinn Féin and their vision of independence on a capitalist basis undoubtedly would have irked Protestant workers in the North and provided ammunition for the propaganda machine of the Unionist establishment. This had a definite impact on the course of subsequent events.

Similarly, Kostick takes issue with Divide and Rule for its criticism of Connolly’s role in the 1916 Easter Rising, claiming Peter Hadden “saw only reactionary politics in the national movement.” These criticisms reflect a misinterpretation of the analysis in Divide and Rule. Peter Hadden uses Connolly’s own description of the nationalist leaders as “the open enemies or the treacherous friends of the working class” to highlight why he believed it was a mistake for Connolly to take part in the Easter Rising in the manner in which he did, without drawing a clear line of demarcation between the nationalist involved and the socialist, working class forces of the Irish Citizens’ Army. He also, like Lenin, outlines why the Rising was premature.

However, Peter Hadden is sympathetic and understanding towards Connolly’s desire to strike a blow against imperialism. He explains that Connolly’s participation in the Rising was born out of frustration with the lack of working-class resistance to the First World War, largely as a result of capitulation of the leadership of the Second International, the majority of whom lined up in support of their own ruling classes.

At the same time, it is no service to Connolly or the labour movement to falsely eulogise him without being prepared to criticise and learn from his mistakes. The most important lesson from this period points to the need for a revolutionary party. A year and a half after Connolly’s execution, the Bolsheviks led the working class to power in Russia, beginning a wave of upheavals that would bring an end to the war. It was an historic tragedy that Connolly was not alive to witness this and to apply its lessons to Ireland. For more analysis on Connolly, we include in the appendix of this edition Peter Hadden’s excellent article The real ideas of James Connolly and we would also recommend Ireland’s Lost Revolution, a publication by the Socialist Party to mark the centenary of the Rising.

Written to prepare socialists for the 1980s

Divide and Rule was written one year after Margaret Thatcher came to power, which itself followed the massive wave of industrial action in Britain known as the “winter of discontent.” In the South of Ireland, a significant mass protest of workers swept the country in 1979. In Northern Ireland, it was a time of recovery for the workers’ movement. In 1980, the Irish Congress of Trade Unions called a day of action against the Tories’ cuts which developed into a half-day regional general strike, the first such strike since the election of Thatcher. Over 50,000 workers marched across the North, including 10,000 in Belfast and 10,000 in Derry.

None of this meant that the Troubles, sectarian division and the complicated issues that flow from them went away, but it did point to the working class as the force capable of overcoming sectarianism and the need for a programme based on class struggle and a socialist alternative. That was evident when the book was written – 1980 saw the first hunger strike against the policy of criminalisation. In 1976, the British government had removed special status for political prisoners. The policy was summed up in Thatcher’s famous comment, “Crime is crime is crime.” The hunger strike was the escalation of a campaign of protest after republican prisoners first refused to wear prison uniform (the blanket protest) and later refused to slop out (the dirty protest). In 1980, the hunger strike came to an end when it appeared the government was granting concessions, only for a second hunger strike to begin the following year, in which Bobby Sands and nine other republican prisoners would die.

How did Peter Hadden and the Militant – forerunner of the Socialist Party – respond to these issues at the time? Firstly, they were steadfast in their opposition to the “sophisticated apparatus of repression” of the British state, while at the same time pointing out that the methods of groups like the IRA were a “blind alley which eventually serves to strengthen the hand of the state against those at which it is directed.”

Crucially, however, they pointed towards united struggle of the working class as the alternative, arguing that the issues at stake should be taken up “in a non-sectarian way by the Labour Movement.” They “fought against the sectarian manner in which the issues were posed” and instead “fought for a class approach, with the Labour Movement taking up the issue in class terms”, arguing that “in Northern Ireland this means united and joint action by Protestant and Catholic workers, for which there can be no substitute. The entire history of the Labour Movement in Ireland and internationally is proof of the crucial role the Labour Movement has. In 1920, when prisoners in Mountjoy Jail began a hunger strike, a General Strike called by the official Labour and Trade Union Movement in support brought success. The power of rallies and marches based on one side of the community is one thing but strike action at the point of production is an entirely different matter.”

This meant taking an independent class position and not simply tail-ending sectarian or nationalist forces. Instead, the Militant advocated a “programme of prison reform to cover all prisoners which would have included the right to wear their own clothes, to negotiate choice of work and training and education, access to the media, unrestricted numbers of letters and trade union rates of pay.” They also argued that the labour movement should review “cases of all those convicted on charges arising out of the Northern Ireland troubles, in order to determine who is, in the eyes of the labour movement, a political prisoner”. They recognised there was a difference between those who “joined organisations like the Provos in the mistaken belief that they were fighting against the present economic system” and those who “were responsible for sectarian atrocities” and were “clearly not political prisoners in any sense in which the labour movement internationally uses the term.” Importantly, while this period saw serious sectarian polarisation, it did not stop important industrial action by workers including significant industrial action in health in 1982.

What has any of that got to do with a book dealing with the period leading up to partition? For Peter Hadden, Divide and Rule was not some academic exercise but about politically arming a new generation of socialist activists with Marxist ideas. Peter Hadden would later point out, “The answers to the questions how and why partition came about shape both our attitude to the national question today and the programme we put forward to deal with it.” The same year, he also wrote a pamphlet on how the labour movement could fight Tory cuts, the title of which summarises this idea – Common Misery, Common Struggle.

Relevance for today

Likewise, the republication of Divide and Rule is not simply for historical interest. Its purpose is to help a new generation of socialist activists to grapple with the national question. For the Socialist Party, our understanding of the reasons for partition and our analysis that the working class could have avoided it also informs our view of how sectarianism can be challenged today.

That is also true of others, including those who take a different view of the national question. For example, Kevin Meagher, in his short book A United Ireland: Why unification is invevitable and how it will come about, states that partition was a “back footed political compromise in order to split the difference between Republicans vying for national self-determination and Loyalists set on having their identity and local hegemony rewarded.” Such a simplistic view, devoid of any analysis of the class forces involved in partition, leads logically to the simplistic conclusion that, based on the demographic trends of today, capitalist reunification is not only possible but inevitable. Similarly, some Unionist historians and others would argue that partition was simply the natural outworking of two nations in Ireland and that remains the case today.

The period Divide and Rule deals with and the period in which it was written have something in common with today, in that we are seeing increasing militancy of the working class. Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, we saw important struggles, including the historic Harland & Wolff shipyard occupation and the largest industrial action of health workers in Northern Ireland in decades. During the Covid-19 crisis too, workers have shown their preparedness to take collective industrial action to defend their health and safety, including the inspiring example of 1,000 workers at the Moy Park site in Portadown walking out in protest against unsafe working conditions. These struggles can be important precursors to even greater battles in the years ahead, which will bring workers – Catholic, Protestant and neither – together.

But it is also likely to be a period of turmoil around the national question, with the dangers of an increase in sectarianism. A key underlying reason is the demographic shift. The 2011 census reflected a watershed moment in Northern Ireland. In 2011, 45% of Northern Ireland’s population identified as Catholic and 48% as Protestant. For the first time since partition, the proportion of the population declaring themselves as Protestant, or having been brought up as Protestant, fell below 50%, even after a statistical adjustment for those who initially stated they had no religion. Analysis of the age structure of the 2011 census suggests that the trend away from a Protestant majority is likely to continue. All of this has led to speculation that the next census in 2021 could see the “ironic situation on the centenary of the state where we actually have a state that has a Catholic majority”, as Dr Paul Nolan, who specialises in monitoring the peace process and social trends, put it.

This demographic shift is having very obvious political effects. The 2017 Assembly election saw the Unionist political parties returned without a majority at Stormont for the first time in the history of the state. The 2019 general election saw more nationalist than Unionist MPs elected. The impact this will have on the psychology and consciousness of both Protestant and Catholic communities cannot be overstated. The idea that the Union between Britain and the North is secure for the foreseeable future is now gone and increasingly the sense exists that a united Ireland is an inevitability.

Added to this is the impact of Brexit, which has again brought the border centre stage, posing the question of hardened borders either North-South or East-West, ie between Britain and Northern Ireland. The new arrangement would mean that Northern Ireland will, alongside Britain, leave the EU customs union but will remain closely aligned to single market regulations, with customs checks on goods travelling between Britain and Northern Ireland, and potentially regulatory checks as Britain diverges from EU standards. This would effectively mean an East-West border.

This only adds to the legitimate feeling of insecurity about the future of many ordinary Protestants. If there is a perception that their identity and the integrity of the Union is being further diminished and that Northern Ireland is being forced into an “economic united Ireland”, it could provoke a serious reaction, as we have seen in the past, such as in response to the Anglo-Irish Agreement, which brought thousands onto the streets in 1985, when the second edition of this book was produced.

Added to this is the effect Brexit, alongside years of Tory austerity, has had in increasing support for Scottish independence, which poses sharply the question of the break-up of the United Kingdom. At the same time, Sinn Féin’s rise in the South – winning more votes than any other party in the general election in March 2020 – adds to the sense of momentum towards a united Ireland.

All this means that it will not be a return to business as usual for the restored Stormont Executive, with ministers presenting a united front until there is an eruption of a crisis. This can be seen in the response to Covid-19 crisis, where open division has reflected itself on various issues. It is likely we will see more conflict on issues such flags, parades, bonfires and language rights, but also in relation to the competing narratives of history. This can be particularly sharp when it comes to events during the Troubles, as seen with the opposition to the prosecution of Soldier F for his role on Bloody Sunday, but it can also be reflected in terms of events around the centenary of partition.

Centenary of partition

The New Decade, New Approach document, which laid the basis for the restoration of the devolved institutions, talks about a programme of events to mark this centenary. Arlene Foster has even talked about the need to mark it in a way that does “not allow it to divide us, but actually to unite us.” However, there is no escaping the reality that Unionists will want to mark it in “in a celebratory way,” with suggestions of inviting the Queen to Stormont, while “there are others who will take a different view”, as Foster acknowledges. Neither a Unionist nor a nationalist interpretation of partition provides any basis for unity. Only a class analysis of the period can point the way to bringing ordinary people together.

To dispel any idea that this centenary will not be controversial, one only needs to look across the border at the fiasco of the recent attempt by the Southern government to commemorate the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), including the notorious Black and Tans. Peter Hadden aptly describes the Black and Tans as embodying “the true spirit of Cromwell, they set about their task, and the toll of their atrocities, the sack of Cork, indiscriminate murder in the Croke Park, etc., is well documented.” In fact, not only is it well documented, the atrocities of the Black and Tans are deeply embedded into the psyche of people in the South and Northern Catholics.

As the Socialist Party explained in an article dealing with this controversy, this commemoration was “part of a broader project, championed by Fine Gael especially, to rewrite history. They have been trying for some time to rehabilitate an especially bourgeois, sectarian and pro-imperialist strand of Irish nationalism, symbolised by John Redmond who convinced tens of thousands to die for Empire in the futile slaughter of World War One. Like the RIC, Redmond and his Irish Parliamentary Party were thrown into the ash-heap of history during the revolutionary period.”

This is particularly important given that the next few years will see the centenaries of many controversial or divisive aspects of Irish history. This, of course, includes the partition of Ireland, but also the Irish Civil War which saw atrocities committed particularly by the forefathers of Fine Gael. This included massive repression and summary execution, often retaliatory, the most infamous being in Ballyseedy, Co. Kerry, where nine anti-Treaty prisoners were tied to a landmine which was detonated, killing eight with one surviving to tell the tale.

Socialists have a responsibility to bring out the real history of Ireland, North and South, particularly the history of workers uniting and the revolutionary potential that existed in this and other periods. This is why the Socialist Party has produced several publications about this important period, including Let Us Rise! The Dublin Lockout- Its impact and legacy (2013), Ireland’s Lost Revolution (2016), Workers’ Power in Belfast (2019) and Limerick Soviet 1919: The revolt of the bottom dog (2019).

In 2017, we published for the first time Common History, Common Struggle, an important book which Peter Hadden was working on at the time of his untimely death in 2010 which, in many ways, is the sequel to Divide and Rule, covering the period after partition up until the late 1960s and the outbreak of the conflict which would become known as the Troubles, with the focus on the revolutionary possibilities at this point. As in the aftermath of partition, “it was the sectarian forces which came out on top after 1969 and it’s their version of events which predominates today. There was nothing inevitable about the rise of sectarianism after 1968. Quite the reverse.”

The period leading up to partition and the events of the 1960s are very clear examples of an important point made in this book which is worth quoting in full here:

“In the hands of those who could press to the forefront the social issues of the day, the national struggle in Ireland was always capable of drawing the broadest support across the religious barrier between the poor. As in 1798, the attempts by the rulers to wield the club of religious bigotry could be faced and answered.

But the opposite too! On every occasion when the pressure of the upper circles of Irish society has succeeded in jettisoning the social issues from the platforms of those advocating national freedom, the struggle has been stamped with a sectional and ultimately a sectarian character. The way has been paved for the British ruling class to successfully intrude the weapon of sectarianism”

Is a border poll the solution?

The demographic shift, the growing sense of momentum towards a united Ireland and the centenary of partition itself will pose the question for many Catholics of how they can actually achieve Irish unity. Sinn Féin have once again laid out their stall, advocating a “unity referendum” in the next five years. The advocates of a border poll rely on the mathematics of sectarian division and the logic of capitalist economics.

They argue that a united Ireland would be a more efficient capitalist entity than the current set-up. In fact, under the status quo of capitalism, a border poll would be a vote on how to share out misery. As Peter Hadden put it in Divide and Rule, “Unity of the capitalist North with the capitalist South is unity of the slums of Belfast with those of Dublin. It would not be the stepping stone to a shining new prosperity that Sinn Féin promise.”

As already mentioned, the mood in Protestant working-class areas is already sombre, and there is real fear for the future. As the demographic balance continues to tip away from the Protestant community, they will not simply shrug their shoulders and accept a capitalist united Ireland. In Divide and Rule, Peter Hadden makes the point that for “Protestants of the North, the idea of a capitalist united Ireland is repellent. Their fear of being submerged in a poverty-stricken Republic, in which they would become the discriminated against minority, remains today as it did during the days of Carson. They would resist such a proposal and resist it with force if necessary.”

Obviously, a lot has changed in the last 40 years but the thrust of this argument remains true today. Thirty years of sectarian conflict in the form of the Troubles have only served to reinforce these fears. In fact, it is the opposition of the Protestatant population, rather than that of the British state, which is the real barrier to a united Ireland.

At the same time, most Catholics have never been accepting of partition and being imprisoned in a state which treated the Catholic population as second-class citizens for half a century. What was once for many a distant aspiration for a united Ireland now seems like a medium or even short-term prospect. There is no solution in holding out for the day when the Catholic working class reconcile themselves to the existence of Northern Ireland, given their experience of decades of poverty and repression which, while less acute today, remains for some sections a present reality.

In our view, a border poll is not an instrument to resolve the national question, but in reality would be a dangerous sectarian headcount, the result of which would be contested by the minority. Each community has national aspirations which cannot be ignored or wished away. Catholics have the right to say no to the continuation of the status quo of the Northern state, but Protestants likewise have the right not to be coerced into a united Ireland. Any form of coercion, that is forcing either community into an arrangement against its will, is impermissible. This includes coercion with a democratic facade – ie, a vote which sees one community out vote the other. This would only represent a continuation and escalation of how sectarian forces have operated during the ‘peace process.’

No capitalist solution

Twenty-two years on from the Good Friday Agreement, sectarian division has not been overcome. The relative ‘peace’ is maintained by dozens of permanent ‘peace-lines’, thousands of armed police and the local enforcement activities of paramilitary groups interested primarily in control of ‘their’ areas. When all this is insufficient, then temporary peace-lines are thrown up and hundreds of extra police are drafted in.

The ceasefire generation got a taste of the past in the tragic killing of Lyra McKee, a journalist and trade union member who was shot dead by a ‘dissident’ republican gunman during a riot in Derry. In many ways, all that has been achieved is an ‘acceptable level of violence’, to borrow a phrase from 1970s Home Secretary Reginald Maudling. Similarly, for many working-class communities, there has been no ‘peace dividend’ since the end of the conflict.

We have more ‘peace walls’ than at the end of the Troubles, and two decades after the Good Friday Agreement promised to facilitate integrated education, over 90% of all school students are still educated in segregated schools. But that is not because ordinary people want it that way. Opinion polls consistently show overwhelming support for integrated education. A similar desire is reflected in the 2018 Life and Times survey, in which 76% said they would prefer to live in a mixed neighbourhood and 91% would prefer to work in a mixed workplace.

The political life of Northern Ireland is riddled with division and crises. The most recent three-year impasse at Stormont exposed once again the fragile nature of the ‘peace process’. This process has failed to resolve any of the key issues facing working-class people in Northern Ireland. When we do have ‘agreements’, such as the recent New Decade, New Approach, they are largely agreements to disagree, to kick the can down the road in terms of the fundamental problems of sectarian division, related to culture, identity and the past. The parties in the Assembly are only capable of agreeing on massive attacks on working-class people: the destruction of jobs and services, and tax cuts for the rich, of course. In this sense at least, all the main parties are cut from the same cloth.

After all, the ‘solution’ of the Good Friday Agreement is rooted in ‘elite accommodation based on a consociational model’. By ‘elites’, the model means literally a handful of people, or even single individuals, ‘representing’ communities. The elite reach an accommodation – that is, they agree to carve up power and resources – and the communities they supposedly represent live separately. The model presupposes no coming together of people on the ground and holds out no possibility of such a coming together in the future.

For some decades, this was the model implemented in Lebanon. After Lebanon achieved independence from France in 1943, there was an agreement between the largest Christian and Muslim groups which set a fixed ratio of seats in the parliament and guaranteed that the President would be a Christian and the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim. It was later agreed that the post of Speaker of the Parliament would go to a Shia Muslim. Demographic changes – particularly the numerical growth of the Shia, the most oppressed of the main religious groups – eventually eroded the basis of this accord. In 1975, it all fell to pieces in the civil war that lasted for 15 years.

Workers’ movement still key

Just as Lebanon points to the failure of such capitalist attempts to resolve the national question, so too does it offer a glimpse at the type of movement needed to challenge sectarianism. 2019 saw a mass movement shake the country in opposition to corruption, mass unemployment and sectarianism, including in an impressive display of unity, with protesters forming a giant human chain along a 105-mile highway, running from Tyre in the south to Tripoli in the north. The action was designed to show how the mass revolt has united people across religious and regional divides. In the aftermath of the resignation of the Prime Minister, the main slogan from the protests was “all of them means all of them.”

In Northern Ireland, the trade unions remain unique as workers’ organisations which unite almost 250,000 workers from Protestant, Catholic and other backgrounds, with membership currently increasing, bucking the trend of recent years. Workplaces are often also the main place in which Catholics and Protestants mix. As in the past, trade unionists have been to the fore in response to paramilitary violence, as was the case after the killing of Lyra McKee.

None of this suits the narrative of any of the sectarian forces, who wish to ignore the role of independent and united working-class action. At key points in the history of the North, the trade union movement was able to mobilise ordinary workers in united action – such as demonstrations, walk-outs and strikes – including in response to sectarian threats or attacks and to isolate sectarian forces.

Take the history of one workplace in Northern Ireland as an example, the Harland & Wolff shipyard – a history often tainted with sectarianism, including the infamous 1920 expulsions of Catholic and socialist workers, including so-called “rotten Prods.” As Divide and Rule outlines, the previous year saw the famous 1919 engineering strike that originated in the shipyards and united workers across the sectarian divide.

Fifty years later, at the start of the Troubles, trade unionists at Harland & Wolff called a mass meeting of the workforce because Catholic workers had not come to work for fear of sectarian attack. At the meeting, senior shop steward Sandy Scott appealed: “If we act as workers, irrespective of our religion, we can hope for an expansion in work opportunities and a better life”. A resolution in opposition to sectarian violence was unanimously passed. The shop stewards then visited the homes of Catholic shipyard workers, successfully appealing to them to return.

Later, when Maurice O’Kane, a Catholic welder, was murdered by the UVF in Harland and Wolff in 1994, shop stewards immediately called thousands of workers out and left the shipyard empty. The shop stewards themselves faced serious threats for this but didn’t buckle. Instead, they followed up this action by turning out en-masse to the funeral in an effort to stare down the killers. Finally, in 2019, a united struggle of Protestant, Catholic and other workers saved this historic workplace from closure.

We don’t have space here to reference the countless other examples of how ordinary trade unionists tried to stop a slide into sectarian conflict and stood up to sectarian paramilitaries, cutting across tit-for-tat killings. For more on that, people can do no better than to read Common History, Common Struggle. While it isn’t possible for sectarian forces to find a lasting solution, it is possible and essential for there to be agreement between working-class people and communities. The working class are capable of coming together in solidarity, entering the stage of history in a decisive fashion as a united force, and finding their way towards socialist ideas.

A major assistance to that process would be the development of a mass working-class political party in the North, and for similar parties to be built in the South and in Britain. These parties will not come into being simply by proclaiming them, but will require events and a new generation moving into struggle. While the situation in the North remains complicated, and there are real dangers inherent in the situation, socialists and those looking for an alternative should be confident that this is possible.

The role of young people

A new generation of young people born since the ceasefires of 1994 are crying out for an alternative. In recent years, they have found themselves in conflict with the social backwardness imposed by the Northern Ireland sectarian parties, especially regarding LGBTQ and abortion rights, and have now won victories when it comes to marriage equality and the right to choose.

An even younger generation has taken part in the international school student strikes in response to the climate crisis. Many were inspired by the movements in support of Corbyn in Britain and Sanders in the US. Socialists should seek to bring out the positive lesson that an alternative can be built, while at the same time pointing to the dangers of a limited approach which seeks to compromise with those hostile to real working-class representation, such as the Blairites in the British Labour Party.

Young people are also frustrated by seemingly forever being imprisoned by Northern Ireland’s past and are rightly impatient for a society where all have the right to live in peace, free from intimidation, division and bigotry. Importantly, recent research from Peter Shirlow indicates that 45% of young Protestants do not identify as Unionists, while 55% of young Catholics do not identify as nationalists.

A major point of Divide and Rule is that Ireland, North and South, is not immune from international trends. In the 1920s, the mass revolutionary struggles here were linked to revolutionary movements in Britain, Europe and indeed across the world. These movements not only challenged capitalism but united workers and oppressed people across the lines drawn by capitalism and imperialism in their efforts to divide and rule. The same was true in the 1960s, when young people in particular drew inspiration from the civil rights movement in the US and revolutionary struggles across the world.

Today, we live in a more globalised society than ever, and many young people have an even more developed internationalist outlook. Struggles across the world inspire each other, as was seen with the mass movements which swept the globe in 2019, from Chile to Lebanon and Hong Kong.

As already mentioned, the central lesson of Divide and Rule is the need to build a working-class alternative, armed with socialist politics and capable of tying together workers in common struggle. If that does not come about, sectarianism will reassert itself, as was seen with the expulsions from the shipyards shortly after the 1919 engineering strike. Similarly, 1932 saw an inspiring and united struggle of unemployed workers in Belfast during the outdoor relief strike, but the failure to build a political force capable of harnessing and channelling this solidarity meant that sectarian pogroms were again the order of the day by 1935. If a socialist alternative is not built, it will not mean an indefinite continuation of an imperfect peace, but a retrenchment back into sectarian conflict.

A new working-class party would be forced to deal with all the complicated questions which sectarian division throws up from its beginning. It could not simply unite people around the ‘bread and butter’ issues and put off discussion on the contentious issues until a later date. Instead, it would have to adopt an independent class position on a range of issues from the outset.

For socialism in Ireland

Most importantly, it would have to strive to raise the sights of working-class people beyond the real problems of poverty and division today, and towards the possibilities inherent in a socialist future. As Peter Hadden summed it up in Troubled Times, “Socialism means taking the major industry and all key services into public ownership and running them democratically, with need replacing profit as the motive. It means no privileged elite, only the right of people themselves to manage their own affairs. It means creating an international brotherhood and sisterhood, a unity based on respect of difference and in which all national and minority rights would be guaranteed. It is the unity of the working class, built in the struggle for such a society that will solve the national problem in Ireland.”

A new mass party must base itself upon the fundamental unity of the working class in the unions, workplaces and in struggles. The maximum unity of working-class people in this island would be the breaking down of all forces that divide us, including the border. The Socialist Party therefore advocates a socialist Ireland, with full and equal rights for all communities, including the protection of minorities.

However, one cannot be opposed to coercion under capitalism but view it as permissible under socialism, which by its very nature is a higher form of democracy, with working-class people in control of every aspect of their lives, instead of the diktats of the markets and CEOs. Protestant working-class people have legitimate fears about a ‘united ireland’. Common struggle can alleviate those fears, but they are deep-rooted.

While not advocating it, socialists should accept the right of predominantly Protestant communities in the North to opt out of a unitary socialist state, with the right to autonomy or even separation. That would not, however, mean the maintenance of the current border, which most Catholics would oppose, but an alternative arrangement, which may be cumbersome, but would be possible to peacefully and democratically agree in a spirit of solidarity, compromise and mutual respect.

Socialism cannot be confined to one country and would require an international struggle to transform society. The Socialist Party is in favour of a socialist Ireland in an equal and voluntary socialist federation with Scotland, England and Wales, which in turn would be part of a wider European socialist federation or confederation. That too would have to be a completely voluntary and equal arrangement, and not based on any form of coercion, as Karl Marx argued when he first raised a similar idea. Writing to his collaborator Engels on the issue of independence for Ireland, he said “after the separation may come federation.”

Such an idea has been derided by those from a republican tradition but, not only would such an arrangement be of practical importance, it is the natural outworking of international working-class solidarity and co-operation, something starkly missing from the capitalist classes’ response to the Covid-19 crisis. Such a demand is also a way of winning the ear of Protestant workers who, unfortunately, associate socialism with narrow Irish nationalism, because of the empty rhetoric of republican groups but also the record of those on the left who have backed them.

We live in a turbulent world. The Covid-19 crisis will be a defining historic moment. Workers will have to organise, fight back and thus learn lessons about the reality of capitalism and the need for socialist change. They will be assisted in that process by looking at the rich history of the socialist and workers’ movement. We are in no doubt that the republication of this book can make an important contribution.

The struggle for solutions to the issues which divide workers, including the national question, is not easy. It’s not for nothing that one of the leaders of the Russian revolution, Leon Trotsky, described the national question as “most labyrinthine and complex”. Nonetheless, the Socialist Party has confidence in the power, capacity and ingenuity of the working class, which has been demonstrated amidst this crisis. If you agree and find this book useful, we encourage you to discuss with us further and join us in the vital struggle for socialist change.