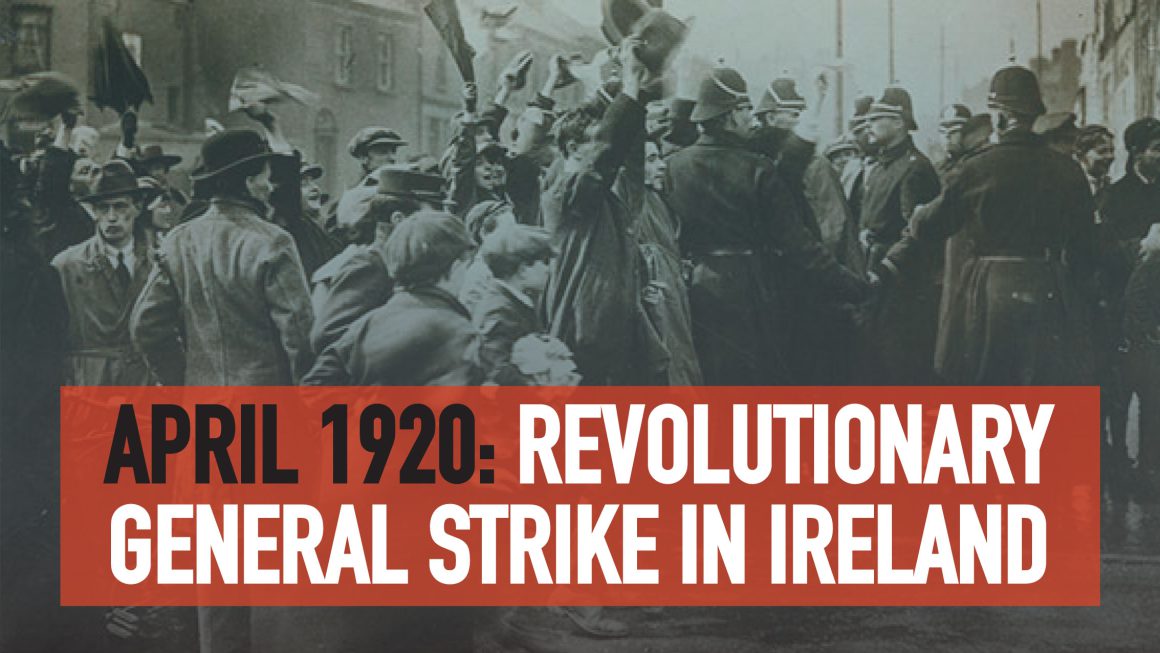

One hundred years ago this month, workers downed tools and took over their workplaces and towns. What began as a hunger strike in prison grew into a general strike against British Imperialism that pointed in the direction of socialism and workers’ power. Manus Lenihan gives an account of these colossal events.

One hundred years ago revolution was sweeping across Ireland and the world. Beginning with Russia in 1917, the working class and poor people mounted a global challenge to capitalism and imperialism. In Europe, empires and ancient monarchies collapsed into dust, and workers’ councils governed whole cities and states, heralding a new era of socialist revolution. In Asia and Africa, oppressed peoples rose up to challenge imperialism. In North America, strikes led to working-class takeovers of whole cities, and gun battles raged in the coal-mining areas.

In the south of Ireland, after the 1916 Rising, a growing mood for independence was intertwined with a desire for socialism and a “Workers’ Republic.” A previously obscure fringe party called Sinn Féin grew to a powerful mass organisation in a few short years. Sinn Féin stood up against British imperialism but envisaged an independent capitalist Ireland. The British ruling class responded with violent repression, which stepped up a gear in 1920.

The nightmare scenario of the British ruling class was socialist revolution in Ireland, spreading inevitably to Britain. After the 1919 engineering strike in Belfast, the Viceroy Lord French was terrified of the potential for socialist and class politics to unite Protestant and Catholic workers.(1) Sinn Féin was equalled, and for a period surpassed, by the trade union movement, especially the militant Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), which grew from 5,000 to 120,000 members between 1916 and 1920. On the back of awesome struggles such as the anti-conscription general strike and the Limerick Soviet, “There was a growing working-class culture in 1920 which openly identified with the Red Flag and took inspiration from the Russian Revolution.” (2) This aroused horror not only on the part of the British authorities, but also Sinn Féin and its armed wing, the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Hunger Strike

By April, raids and police informers had filled the cells of Mountjoy. The Black and Tans, paramilitaries recruited to fill the thinning ranks of the police, began a sadistic rampage across Ireland. There were 4,000 military raids in February alone (3) and the blows landed on labour as much as on Sinn Féin. Every other week the authorities confiscated or sabotaged the Watchword of Labour, in whose pages reports on the Russian Revolution jostled for space with accounts of farm labourers’ victories in small Irish towns. Union offices were ransacked, meetings were broken up and trade union officials were interned without trial.

In April, prisoners began to strike back, supported by huge numbers on the outside. From the 11th, crowds heaved against a line of soldiers outside Mountjoy Prison. Inside, behind the bayonets and barbed wire, ninety men were on hunger strike. They were behind bars for unlawful assembly, possession of arms, drilling and “making seditious speeches;” half were convicted and half were internees. As well as refusing to eat, they had tunnelled through cell walls and smashed up every stick of furniture. The strike was as much a socialist initiative as a republican one: among the strikers, trade union militants were at least a “considerable proportion” or possibly even “the greater party.” Every night the starving men sang songs, and every night they finished with “The Red Flag.”(4)

Jack Hedley

Among the leaders of the hunger strike was someone who embodies the working-class and internationalist politics of the time: Jack Hedley, alias Sean O’Hagan. An English socialist drafted into the British navy, Hedley jumped ship in Belfast in 1918. He was baited by the press and by sectarian bigots as a result of his activity during the historic January 1919 Engineering Strike in Belfast, also known as the “Belfast Soviet”: “The black north can take care of itself anyway, without either Larkins or O’Hagans or Russian jews.”(5) That summer he was arrested with books by Marx and Lenin in his pockets, and jailed for “a speech approving the Russian soviet system, and advocating its adoption in this country.” (6)

He was one of the “Red-Socialists” identified by the press as the organisers of a 100,000-strong march from Donegall Place to Ormeau Park in Belfast on May Day 1919.(7) His comrades include Sean Dowling, who was a close comrade of James Connolly and the “philosophical begetter” and a leader of the Limerick Soviet.(8) In 1920-22 Hedley and his comrades went on to lead the “Munster Soviets”, which saw workplaces and towns occupied by workers across the province. Hedley and the other socialist prisoners wanted to strike for unconditional release, but the republicans successfully argued for the more limited demand of prisoner-of-war status.(9)

Protests on a knife-edge

The prison medical officer warned that the men were soon going to start dropping dead among Hedley and his fellow hunger strikers. The crowds outside the gate swelled to tens of thousands of men and women, trampling barricades, defying tanks. The soldiers fired volleys over their heads. A fighter plane swooped down and flew “along a broad street below the eaves of the houses.” The idea of machine-gunning the crowd from the air had been considered.(10) Some of the protestors had revolvers in their pockets and their task was simple: if the “Tommies” (British soldiers) would shoot, they would shoot back. The confrontation was on a knife-edge. In Amritsar, in Punjab in India, one year ago almost to the day, British troops gunned down 400 peaceful protestors. Was that bloodshed about to be repeated? Or perhaps the prison is about to be stormed by the masses like a 20th century Bastille.

Socialists were in the crowd, appealing to the soldiers not to fire. The “Tommies,” privates and NCOs, were in general more sympathetic than the officers, Black and Tans or Auxiliaries. Working-class British soldiers – “our fellow trade unionists in khaki”(11) – were aware of colossal strikes going on in Britain, involving their friends and neighbours. The year previously, mutinies broke out in the British army, culminating in the creation of a soldiers’ soviet of Calais. If it came down to it, the troops might have refused to fire.

But there were restraining influences on the other side. Sean O’Mahony, a Sinn Féin TD and businessman, organised a cordon of priests to push the crowd back. The role of Sinn Féin and the Catholic Church in these events is to urge restraint and to dampen down the struggle.

The General Strike

It was the organised working class that liberated the prisoners, broke the barricade and ended the hunger strike. On 12 April the Irish Trades Union Congress executive issued the call for an indefinite general strike for the unconditional release of the hunger strikers. The word went out in the evening papers, by telegram and on the mail trains.

In Dublin, rail workers at Broadstone and Inchicore downed tools and marched on Mountjoy. Work stopped in every part of the city. For the next three days, large parts of Ireland experienced scenes you would expect to see only in a socialist revolution. Workers’ councils take over many towns, “formed not on a local but on a class basis.”(12) Roving pickets with bricks and sticks kept businesses closed. Factories, offices, schools and shops were shut, marts and fairs were dispersed. Stocks of food and coal were seized and their distribution was overseen by workers. Motor vehicles, then a rare commodity only owned by businesses and the affluent, were halted. Workers’ councils appointed police forces and issued permits.

Incredible reports came in from a long list of towns. In Kilmallock, Co Limerick: “At one table sat a school teacher dispensing bread permits, at another a trade union official controlling the flour supply – at a third a railwayman controlling coal, at a fourth a creamery clerk distributing butter tickets… all working smoothly.”(13) Waterford, meanwhile, was “taken over by a Soviet Commissar [a railway worker] and three associates. The Sinn Féin mayor abdicated. For two days […] the city was in the hands of these men.” The workers were benevolent conquerors: in Cavan, says a laconic report, “one RIC man attempted hold up of parade with baton; life spared on recommendation of leaders.”(14)

“A remarkable feature […] is the ever-present nature of the word Soviet.” (15) Along with phrases like “Bolshevik” “Red Guard” and even “Commissar,” this showed the internationalist outlook and socialist politics of the strikers. For a great number of the strikers, this mass action was part of a global struggle not just against imperialism but against capitalism.

“Staggering blow” to imperialism

The main imperial authorities on the ground in Ireland were Lord French and Commander-in-Chief Macready. On 13 April the British cabinet instructed them to concede prisoner-of-war status to the hunger strikers. This demand was unthinkable for the British ruling class just a few days before that; now it became unthinkable for the hunger strikers. They rejected it.

French and Macready were terrified by the general strike, and the cabinet in London, to save itself from humiliation, had washed its hands of the matter. French and Macready decide to free the prisoners. They fumble for a fig leaf to cover their shame, and offer to release the prisoners “on parole.”(16) But again the prisoners refused the deal. They would not sign parole papers. The authorities were forced to release them unconditionally – anything, to put an end to the strike. Maintaining their stiff upper lip to the very end, the authorities read “parole conditions” out loud to their former prisoners as they walked out. It was Tory leader Andrew Bonar Law who teared away the last shred of dignity from the proceedings, pointing out that half of the hunger strikers were never in any case entitled to parole! The reality was that the prisoners have not been “paroled” but liberated by mass action.

This moment was a decisive turning-point in the struggle against imperialism. The morale of their forces is devastated and many of their gains since January wiped out. With former prisoners at large, the touts who put them behind bars were “virtually driven off the streets.” Historian Charles Townsend describes it as a “staggering blow.”(17) The armed power of the state was countered by united working-class action, and the newspapers were full of reports of soviets; it was all a very dramatic indication of the potential for socialist revolution. This accelerated the turn of the British ruling class from simple repression to a compromise with Sinn Féin and unionism in the form of the “divide and rule” strategy of partition.

Lessons

The General Strike of April 1920 represented a victory of masses of organised workers, both women and men, not of a few politicians, or even of guerrilla flying columns. It hammered home again the lesson that, in the words of James Connolly, “only the Irish working class remain as the incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland.”(18) The strike demonstrated workers’ ability to shut down industry, services and transport. (Later that year, underscoring the point, transport workers began their refusal to carry British troops and munitions). It also showed, at every stage, that workers were willing to go further and sacrifice more in the struggle.

Crucially, the labour movement could have put forward a programme to appeal to Protestant as well as Catholic workers. The reactionary politics of unionist politicians like Edward Carson and James Craig faced a stiff challenge from socialists. When Labour candidates won 12 out of 60 seats in the January 1920 local elections in Belfast, a Dáil document described the vote as “not Carsonite but clearly internationalist.”(19) The vision of Sinn Féin, on the other hand, based on tariffs and likely to be dominated by the Catholic Church, held no attraction to Protestant workers.

Tragically the key labour leaders, while revolutionary in words, were conservative in deeds. Their approach throughout the period was to support Sinn Féin, never to make any serious challenge to them. Had the workers’ movement acted as an independent force with its own programme, putting its own stamp on events, not only could Protestant workers have been won over, but “there was every danger that this class war might be carried into the ranks of the republican army itself”(20) due to the class character of the rank-and-file of the IRA and broader Republican movement. On the basis of a worker-led, secular and anti-sectarian movement for socialism and against imperialism, the bloody tragedy of partition and civil war could have been averted.

Role of republicanism

In the wake of the 1920 General Strike the unionist Irish Times taunted republicans: “A continuation of the fight which ended yesterday might have witnessed the establishment of soviets of working men in all the ports of Ireland.” The message to Sinn Féin was: this is just as much of a problem for you as it is for us; “Sinn Féin as a body is anti-socialist… They are beginning to appreciate – now that it has disappeared – the merits of the Pax Britannica [British rule in Ireland].”(21) There was no word of a lie. Sinn Féin and the IRA were fundamentally hostile to working-class struggles. Some elements of Sinn Féin and the IRA sometimes played a role in struggles or voiced radical phrases, but that doesn’t change the general picture. Later the anti-treaty republicans offered nothing fundamentally different, and proved hostile to independent working-class action. Various strikes and land struggles of 1920 were described by Sinn Féin’s Ministry of Home Affairs as “a grave menace to the Republic.”(22)

Such a total and unqualified victory as the April 1920 General Strike is a rare thing to find in the history books. Unfortunately, accounts of it in history books are often just as hard to find. These events, and the stories of individuals like Jack Hedley, have been saved from oblivion thanks to the work of labour and socialist historians.

Hedley, Sean Dowling and their comrades founded the Revolutionary Socialist Party in 1919. Indicating the excitement with which it was received, it drew 500 people to one meeting in Belfast. Under pressure of titanic events and the blows of state repression, the RSP did not survive, but it shows the potential that existed. Even a small party, provided it was built and tempered in advance, could have grown and played a decisive role, unleashing the full potential of the workers’ movement. The Syndicalist politics of many workers’ leaders of the time meant they may have failed to draw out the full lessons of the Russian Revolution – on the need for a revolutionary party, without which a revolutionary movement, no matter how powerful, will “dissipate like steam not enclosed in a piston-box.”(23)

That the ingredients for such a party did in fact exist is proved by the role played by workers’ leaders – cadres – like Hedley and Dowling and their comrades. Their stories draw together elements which may seem disparate at first glance. April 1920 found Hedley starving in the cells of Mountjoy while outside, workers seized control of town after town; a red thread connects this moment to James Connolly, to the Russian Revolution, to the great strikes of 1919 in Belfast and Limerick and to the workplace soviets in Munster with their great slogan, “We make bread not profits.” This connecting thread is working-class struggle and socialist revolution, a political programme best summed up in a report from the West of Ireland during the General Strike of April 1920:

“Well, the Workers’ Council is formed in Galway, and it’s here to stay. God speed the day when such Councils shall be established all over Erin and the world, control the natural resources of the country, the means of production and distribution, run them as the worker knows how to run them, for the good and welfare of the whole community and not for the profits of a few bloated parasites.”(24)

Notes:

1. Hadden, Peter, Troubled Times: The National Question in Ireland, 1995, Chapter 5 https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/hadden/1995/natq/ch05.html

2. Bradley, Dan, Farm Labourers: Irish Struggle 1900-1976 (Athol Books,1988), 55

3. O’Connor, Emmet, Reds and the Green: Ireland, Russia and the Communist Internationals 1919-43 (UCD Press 2004), 33

4. Kostick, Conor, Revolution in Ireland: Popular Militancy 1913-1923 (Cork University Press, 1996) , 129-130

5. Morgan, Austen, Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1901-1923, Pluto Press, 1991, 235

6. “Belfast Sedition Case,” Irish Independent, Friday, February 6th 1920

7. Kostick, Revolution in Ireland

8. Haugh, Dominic, “More than a taste of power”, in Let Us Rise, Socialist Party, 86

9. “The view of the latter section, which was composed entirely of volunteers, prevailed and a demand for prisoner-of-war treatment made” – Captain Henry S Murray, Bureau of Military History, Witness statement BMH.WS060, available online

10. Townsend, Charles, The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence 1918-1923, Penguin, 2013, 143

11. Limerick Soviet “Workers’ Bulletin,” quoted in Cahill, Liam, Forgotten Revolution: Limerick Soviet 1919, O’Brien, 1990, 95-96

12. Manchester Guardian, quoted in Costick, “The Biggest General Strike in Irish History”, https://independentleft.ie/irelands-biggest-general-strike/

13. Kostick, “The Biggest General Strike in Irish History”

14. Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, 132; Sóbhéidí na hÉireann, TG4, available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QIIX8GfkrKs&t=945s

15. Fallon, Donal, “Ireland’s Greatest Strike”, https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/04/irelands-greatest-strike/

16. Townsend, 144

17. Townsend, 144

18. Connolly, James, Labour in Irish History, Foreword

19. Haugh, Dominic, “Socialist Revolution in Ireland: A Lost Opportunity” in Marxist Perspectives on Irish Society, eds Flynn, Clarke, Hayes, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011, 14

20. Dáil Ministry of Home Affairs, 1921, quoted in Haugh, 15

21. Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, 129

22. Haugh, 15

23. Trotsky, Leon, The History of the Russian Revolution, 1932, Vol 1, Preface, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/hrr/index.htm

24. Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, 131