The horrors of the First World War, deteriorating living standards and the inspiring example of the Russian Revolution lit the fuse for revolutionary upheaval in Germany in November 1918. Workers’ power and socialist revolution were the order of the day. Matt Waine looks at the lessons of these events and their historic significance.

On the second weekend of January 2019, over 40,000 people made their way to the Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde cemetery in east Berlin to pay their respects at the graves of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. These two socialist leaders were murdered 100 years ago by the Freikorps, the proto-fascist militia, on the orders of their former comrades in the leadership of the Social-Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The simple obelisk at the grave bears the ominous epitaph, “Die Toten mahnen uns” – “the dead remind us”.

The Tiergarten park in the centre of Berlin was the scene of these grisly murders. There, at the Lichtenstein bridge, the body of one of the greatest socialist revolutionaries, Rosa Luxemburg, was dumped into the freezing Landwehrkanal. At around the same time, in another part of the park, her comrade and collaborator Karl Liebknecht was murdered, with his body disposed of anonymously in one of the city’s mortuaries. Their deaths brought to an end two months of revolutionary fervour and upheaval that saw the declaration of a workers’ republic, with Luxemburg and Liebknecht the leaders.

The centenary of these events has provoked much comment in Germany as political instability, economic uncertainty and the growth of the far right haunt the political establishment, none more so than the SPD which, 100 years later, cannot seem to excise the ghosts of Luxemburg and Liebknecht. Writing of the events of 1919 in the Frankfurter Rundschau, former vice-chair of the SPD, Wolfgang Thierse, said: “But what choice did the Social Democrat-led government have?… but one can know that the path that was taken was the better one.”1

War and revolution

“War is the mother of revolution,” wrote Leon Trotsky. And so it was in Germany. On 9 November 1918, the 400-year rule of the Hohenzollern monarchy collapsed and Germany sued for peace – in terms understood to be a complete surrender – thereby bringing the First World War to an end. Four days earlier, the sailors of the German High Fleet mutinied at the Baltic seaport of Kiel. They elected a sailors’ and workers’ council, and raised the red flag of socialist revolution over the vessels.

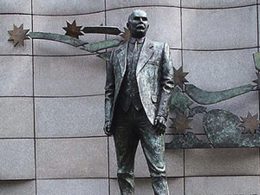

In Berlin, earlier that day, Phillip Scheidemann, chairman of the SPD, had hurriedly declared the formation of the German republic from the balcony of the Reichstag to tumultuous applause from an enormous throng of people below. All across Germany workers’ councils were being established and red flags were flown from barracks to state buildings. The impressive, impervious and world-renowned efficiency of Prussian autocracy and militarism had melted away. Power now rested in the hands of the SPD.

Four years earlier, on 4 August 1914, the SPD deputies went into the Reichstag and voted for the War Credits – a special budget for financing the war. It was a bombsell to the world socialist movement; so much so that Vladimir Lenin, who would lead the Russian Revolution in 1917, refused to believe it, even dismissing the issue of Vorwärts (the SPD daily paper) as a forgery of the German high command.

Historic betrayal

The SPD had been the model of European Socialism. Its official doctrine was Marxism and its main theoreticians and leaders were supporters and students of Marx and Engels. The unification of Germany in the 1860s had unleashed massive productive forces and the expansion of the German industrial economy, which in turn created the largest working class in Europe. Through patient and persistent work, toiling through repression in its early years, the SPD had by 1914 a membership of 1,100,000; a staff of 3,000; 90 daily newspapers employing 267 full time journalists; 2,886 local elected councillors; and 110 members of the Imperial Reichstag – making it the largest parliamentary fraction.2

As Ruth Fischer explained,

“The German social democrats were able to realize a type of organization that was more than a loosely knit association of individuals coming together temporarily for temporary aims, more than a party for the defence of labour interests. The German Social Democratic Party became a way of life. It was much more than a political machine; it gave the German worker dignity and status in a world of his own. The individual worker lived in his party, the party penetrated into the workers’ everyday habits. His ideas, his reactions, his attitudes, were formed out of this integration of his person with his collective.”3

So how then did this magnificent machine of working-class political organisation find itself on the same side of the Kaiser in 1914? The long upswing of European capitalism in the last quarter of the 19th century provided a new objective reality for the emergence of a reformist current within the SPD personified by Eduard Bernstein. He argued that capitalism had appeared to overcome its chaotic boom-bust cycle which allowed for the possibility of a gradual and peaceful evolution of society towards socialism. The steady growth in support for the SPD and the reforms won from the German state seemed to endorse Bernstein’s contentions. Rather than the growing impoverishment of the working class, as predicted by Marx, capitalism was being forced to share out the fruits of its growth. Marxism, contended Bernstein, needed to be revised, brought up to date.

In this battle, Bernstein won the support of the growing bureaucracy of functionaries in the party and the trade union leaders, who saw this perspective offering an easier path for their careers. It fell to the party’s main theoretician, Karl Kautsky, but especially the brilliant Rosa Luxemburg, to challenge and refute Bernstein’s revisionism. Luxemburg’s seminal pamphlet, Reform or Revolution, even today, is a fantastic refutation of opportunism and reformism. While Bernstein’s revisionism was rejected at the party congress in Dresden in 1903, the process of moving the party away from its Marxist principles and adopting a reformist method continued.

The test of war

The declaration of war in August 1914 was not unforeseen. Indeed, what to do in the event of the outbreak of a world war was something that occupied the minds of all socialists. The Second International had committed itself to opposition to imperialist wars, with aims of encouraging the European working class to rise up and stop the war with a general strike. However, when war eventually came to the door of the SPD, the majority of its deputies supported the defence of the Fatherland and voted for the war credits in the Reichstag.

Whilst this eventuality was not widely anticipated in advance of the war it was in fact the culmination in practice of the perspective argued for by Bernstein. If socialism was to be achieved by a peaceful, gradual evolution of German capitalism, then it followed that the German capitalist class must be defended in the war. Through the practice of effectively reconciling itself with the system of capitalism, the SPD supported its most important institution; war.

Of course the war was not a short affair. The colossal clash of empires saw millions of workers mobilised and the most modern military technology matched with the most primitive barbarism, resulting in the massacre of nine million working-class combatants and seven million civilians. It was horror on a scale never before imagined. At home, the SPD agreed to the policy of Burgfrieden, a suspension of class struggle to allow for the uninterrupted exploitation of the working class in the name of the war effort. Everyone available was drafted to the front, or to the war industries. The weekly rations were eroded month after month, with starvation, influenza and other diseases claiming hundreds of lives in the capital on a daily basis. Inflation reduced workers’ meagre wages even further and banks began to collapse. Anger at these inflictions encouraged a steady increase in strikes and protests and a growing anti-war sentiment.

By 1916, after five more votes for increased war credits, the mood had begun to change. The left inside the SPD had begun to find its voice and an echo, and in January of that year, a split occurred resulting in the creation of the “Independent SPD” (USPD).

Outbreak of revolution

By October 1918, Germany was on the verge, not only of military defeat, but also of socialist revolution. The SPD leaders finally became aware of the growing support for revolutionary ideas.

“With a chill, the Majority Socialists (SPD) began to realise how much ground they had lost to the Independent Socialists and especially the extreme-left-wing factions…Only a few weeks before, the Majority Socialists had been absolutely confident of their authority within the working class… Philip Scheidemann, who had advocated Liebknecht’s release on the grounds that he was much less dangerous outside prison, was frankly dumbfounded – ‘Liebknecht has been carried shoulder high by soldiers who have been decorated with the Iron Cross. Who could have dreamt of such a thing happening three weeks ago!’”4

In the maelstrom of the developing German Revolution, the masses had begun to look for a way out of the chaos. The propaganda and agitation of Luxemburg and Liebknecht, calling for a workers’government on Soviet lines, was embraced by wide and growing sections of the working class. As the old regime began to crumble, Germany was entering a period of ‘Dual Power’ with workers’ councils and the capitalist state vying for control.

Almost to the eleventh hour, the policy of the SPD was to save some sort of ‘constitutional monarchy’, until it was clear that the risen masses had moved beyond the idea of even a ‘constitutional democracy’ and had begun to establish democratic workers’ councils. Now the policy of the SPD was to save capitalism from the threat of a Soviet state being established in Germany.

The SPD, with its multi-layered bureaucracy and experienced professional organisers, had learned some of the lessons of the Russian Revolution. Instead of opposing the occupations and establishment of workers’ councils, they sought to acquiesce to them. In some areas, it was SPD functionaries who even set them up.

Sailors revolt in Kiel

In Kiel, Gustav Noske was despatched to dampen down the revolutionary energy of the workers and sailors who had seized power. He immediately acceded to many of the sailors’ demands – arranging for payment of wages, releasing imprisoned mutineers, allowing the red flag fly over vessels. But he also insisted on ‘Ruhe und Ordnung’ – peace and order. The sailors were convinced to hand over their weapons to the Supreme Council, which had been hand selected by Noske himself.

But what had happened in Kiel had sparked off movements across the country. “Reports were reaching Berlin that in almost every army regiment, men were electing ‘barracks councils’ which in turn combined with other regiments in the same city to elect a ‘garrison council.’”5 These developments had an ominous familiarity with events in Soviet Russia. The SPD leadership had to act quickly to stem the tide.

Freidrich Ebert, leader of the SPD, insisted on the abdication of the Kaiser. Reichskanzler Prince Max von Baden, before he sought the Kaiser’s abdication, called Ebert and asked him directly, “If I should succeed in persuading the Kaiser, do I have you on my side in the struggle against the social revolution? Without hesitation, Ebert replied, “If the Kaiser does not abdicate, the social revolution is inevitable. I do not want it – in fact, I hate it like sin.”6

In Bavaria, Ludwig III had been deposed and a workers’ government declared. It was similar in Dusseldorf, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Leipzig, and many other cities. The general strike, called by the USPD and the Spartacists for 9 November, was enormous.

Faced with an imminent revolution, the SPD had no choice but to support the general strike, try to put themselves at the head of the movement in order to divert it down a non-revolutionary road. For the next two months, it was a battle not only for the leadership of the German working class, ultimately the fate of world history was in the balance.

The USPD and the KPD

The day after Scheidemann declared the German Republic from the Reichstag balcony, the SPD proposed the establishment of a ‘Council of People’s Commissars’ – adopting the same name as the government declared by Lenin in Russia just a year previously. Alongside the three SPD members, three seats were offered to the USPD. They even hinted that Karl Liebkneckt would be welcome to join!

The USPD was a ‘centrist’ political force, meaning that it vacillated between revolution and reformism, but always came down on the side of the latter. They insisted that their participation in this government was necessary in order to defend the gains of the socialist revolution. From the point of view of the revolution this was in fact a critical mistake. The SPD leaders had no intention of consolidating the socialist revolution that was taking shape, their aim was to crush it.

The German Revolution was throwing up many of the challenges, obstacles and similar political forces as had the revolution in Russia in 1917. Critically,

what was missing was a distinct revolutionary party, something Lenin and the Bolsheviks had consciously and patiently built in Russia. There was no shortage or revolutionary initiative and groups with a willingness to sacrifice. For example, the Obleute, Revolutionary Shop Stewarts Group in Berlin, were small in number but had massive influence among the working class, particularly the industrial working class. Hundreds of thousands of revolutionary-inclined workers had joined the USPD, but none of these groups had the cohesion, the steeled and tempered political leadership that the Bolshevik Party had. Lenin had determined that such a party was necessary to lead the working class through to the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of a workers’ state. His concept of the party was confirmed by the victorious October Revolution.

Unfortunately, neither Luxemburg nor Liebknecht grasped the need for such a party fully, until it was too late. The Spartacist group had enormous support, but it wasn’t organised as a cohesive revolutionary party with a tested and experienced cadre. As Leon Trotsky, the co-leader of the Russian revolution said, “Without a guiding organization, the energy of the masses would dissipate like steam not enclosed in a piston-box. But nevertheless what moves things is not the piston or the box, but the steam.”7 In that sense, there was plently of steam in Germany in 1918, but there was no piston-box. It was not until 30 December that the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was founded.

SPD manoeuvring

Immediately after the establishment of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars government, the SPD set about trying to rein in the disparate and chaotic workers’ and soldiers’ councils that had sprung up around the country. Ebert called for a national congress of all the various councils for December. It was a nod in the direction of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets that became the new state power in revolutionary Russia. However, without a Bolshevik-type party to contend with, and using the enormous apparatus of the SPD and its connections with the trade unions, the delegates were packed with SPD Yes-men. Indeed, of the 489 delegates, only 187 were waged or salaried workers, the rest being trade union or SPD officers.8 At the National Congress, the crushing majority enjoyed by SPD was used to reject the call for the socialist transformation of society.

Revolution is nothing other than the conscious interference of the masses into political life. Trade union membership rose from 2.8 million in 1918 to 7.3 million the following year. The SPD say its membership climb from 250,000 to 500,000 in a year, with the USPD jumping from 100,000 to 300,000 in four months!

However, this also served to dilute the experienced and more revolutionary-minded workers. This had happened to the Bolsheviks who were a small minority in the soviets as hundreds of thousands of workers took their first tentative steps into political activity. But the political perspectives of the Bolsheviks, in understanding the stages of the revolution, patiently explaining its ideas to workers over the course of a number of months and allowing them to go through the experience of the actions of the reformists in whom they had initial illusions, won a majority of the working class to its programme by October.

The SPD manoeuvre at the national congress of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils did not stem the revolutionary tide. There were violent protests and skirmishes between frustrated workers and state forces, including an attempt to arrest Karl Liebknecht in early December, whereupon 150,000 demonstrated in Berlin. The supreme command-inspired ‘National Congress of Soldiers’ Councils’ was an attempt to nullify the soldiers councils, but provoked a backlash from the troops who were moving increasingly in a revolutionary direction. More and more the SPD were forced to resort to state repression, including the newly formed proto-fascist Freikorp forces, to stem the tide. This led to the events of ‘Bloody Christmas’, where the police force (under the orders of the SPD) violently attacked the revolutionary ‘People’s Naval Division’.

The attack was too much for even the USPD to accept and their three representatives in the Council of Peoples’ Commissars resigned, replaced by three more representatives from the SPD, including Gustav Noske. On accepting the portfolio of Minister for Defence – a position which would put him personally in charge of suppressing revolutionary workers, he was reported as saying, “someone must be the bloodhound. I won’t shirk the responsibility”9

The remnants of the old state could not tolerate the lack of order. They had placed their faith in the SPD to rescue Germany from Bolshevism. They wanted the Ebert Government to move more decisively against the growing revolutionary unrest.

Premature action

The art of revolution is about being able to read the tempo and development of consciousness of the masses, understanding that consciousness among different sections develops in different stages. Whilst the more revolutionary-minded and experienced workers grew impatient at the SPD government and were suspicious of their real motives, the newly active elements had to go through certain experiences themselves before they could really draw the necessary conclusions. This was the case in July 1917 in Russia. The Petrograd working class was armed and ready to overthrow the Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky, but Lenin understood that the the working class, soldiers and peasantry in the rest of Russia were not ready for that and a premature uprising in the city might actually derail the revolution.

The SPD cynically recognised this impatience, and while still paying lip-service to the ideas of socialism, tried to provoke a response from the working class. The events around Bloody Christmas were a big blow to Ebert. He had overstepped the mark by calling in the army to shoot on revolutionary sailors and had pinned his colours to the mast. There was nothing to do but continue on attacking the left. At the end of December, the SPD Government demanded the removal of the police chief of Berlin, Emil Eichhorn, who was a member of the USPD. In response, the USPD, the Obleute and the newly formed KPD called a mass demonstration for 5 January. The stage was then set for a direct conflict between the state forces and the advanced sections of the Berlin working class.

An enormous throng of hundreds of thousands of people, many bearing arms, took to the streets, fearing that the SPD were moving to crush the incomplete revolution. The size of the protest surprised even the organisers. Whilst the USPD, the KPD and the revolutionary shop stewards had been in full agreement that it was not possible to overthrow the Ebert government at this stage, the sheer volume of protesters and their determination introduced the element of doubt – maybe it was time? The leaders met for two days to discuss what should follow, while the masses returned to the streets on the second day.

Finally, a large majority of the leaders agreed that it was time to overthrow the government, announcing the formation of a Revolutionary Committee of 52 to lead an insurrection. By that stage, the impatience of a section of workers led to the occupation of the SPD’s Vorwarts office and other enterprises. The leaders of the Revolutionary Committee had banked on the support of soldiers and sailors, which turned out to be a miscalculation. But they had also over-estimated the mood of the protesters. As historian, Richard M. Watt, noted: “Despite the hundreds of thousands of strikers, there were altogether less than 10,000 men determined to fight… The mass of the Berlin workers were ready to strike and demonstrate, but not to engage in armed struggle.”10

The counter-revolution

By the evening of 6 January, it was clear the situation had begun to slip. The National Committee of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils endorsed the call for Eichhorn’s dismissal. Noske moved into the Freikorp headquarters and prepared for a counter attack. The SPD leadership were able to paint the occupations of Vorwarts and the armed demonstrations as a dictatorial attempt by Bolsheviks to overthrow the newly established democracy. Negotiations between both sides broke down and as the USPD began to waver. Liebknecht called for an armed uprising, while the Berlin working class looked on in shock – two armed groups, both calling themselves socialists, preparing for civil war. Meetings in the factories called for an end to the conflict.

Ebert’s government used the confusion and aspirations for unity among the wide working class to move decisively against the insurgents and after a number of days, all the main districts of the city were under government control.

With all the revolutionary leaders either killed, arrested or forced into hiding, the opening chapter of the German Revolution came to an end. But for the SPD, whose former Marxist education told them that the revolution itself was not ended, moved to decapitate a future, more-prepared and ultimately successful revolution. The ‘Bloodhound’ Noske set as his target the annihilation of Luxemburg, Liebknecht and the KPD leadership, setting his crazed Freikorp dogs onto their trail. On 15 January, the two were discovered in the Wilmersdorf area of Berlin, arrested, brutalised and murdered that night.

A tragic end

1918-19 saw the opening up of a period of revolutionary and counter-revolutionary turmoil in Germany, with ebbs and flows, that lasted until 1923. For Marxists, these are not chaotic affairs, but flowed from the war and the historic crisis of capitalism that this came from. This in turn resulted in the mass of working people looking for a way out of the crisis and following the path of revolution. What Luxemburg and Liebknecht lacked was not an understanding of this, or revolutionary determination and courage – but a revolutionary party. The valiant attempts to weld such a party into existence in the middle of the unfolding revolution between November and January was too late, its reach too little and its experience too short.

Four days before her death, on 11 January, Luxemburg tragically drew the lessons of the defeat:

“The absence of leadership, the non-existence of a centre to organise the Berlin working class, cannot continue. If the cause of the Revolution is to advance, if victory of the proletariat, of socialism, is to be anything but a dream, the revolutionary workers must set up leading organisations able to guide and to utilise the combative energy of the masses.”11

Notes

1. Jan Sternberg, Frankfurter Rundschau, 13/1/2019, www.fr.de

2. Pierre Broue, 2006, The German Revolution 1917-23, Merlin Press, p. 15

3. R. Fischer, 1948, Stalin and German Communism, Cambridge, MA., p. 4

4. Richard M Watt, 2003, The Kings Depart, Phoenix, p.173

5. Ibid p. 182

6. Ibid p.183

7. Leon Trotsky, The History of the Russian Revolution, Preface, www.marxists.org

8. Pierre Broue, 2006, p. 184

9. Richard M Watt, 2003, p. 239, also in Noske’s memoirs, Von Kiel bis Kapp

10. Pierre Broue, 2006, p. 246

11. Ibid p. 253