By Kevin McLoughlin, first published in December 2016 in the Socialist Party’s book Ireland’s Lost Revolution, The Working Class and the Struggle for Socialism

The 1916 Rising was the start of a revolutionary process that engulfed the whole of Ireland, North and South, for a number of years, in which the working-class movement reached a level of unity and political development not seen before or since.

Why wasn’t this revolution successful? Why did the hopes and potential for a unified national struggle and social liberation instead end in the sectarian division that still exists to this day?

The immediate reaction to the Rising was shock, with the majority viewing the event and its timing negatively. This wasn’t completely universal of course. Those who held dear an aspiration for Irish independence and freedom would have had a more sympathetic view of the action, but the majority either opposed it, questioned why it had taken place or were ambivalent towards it. Many still had some hopes in the idea of Home Rule.

In the north-east of the country and among the Protestant community in particular the Rising provoked stronger opposition. There was already deep suspicion or opposition to Irish nationalism among Protestant working-class people, but on top of that, significant numbers from the Protestant community had joined the British Army to fight in the First World War. To them, the Rising was perceived as an attack on the war effort and on those who were fighting in it.

However, beneath the surface, important changes were already taking place in attitudes to the war and to capitalism itself. This was the backdrop for the change in attitudes to the Rising and Britain’s control in Ireland, particularly in the southern part of the country. As the days and weeks passed, the magnitude of what had occurred began to dawn. With the huge damage inflicted and the numbers of human casualties, so too did a new realisation about what British rule in Ireland really meant.

Revolution & counter-revolution

Overall it was the vicious regime of repression and terror meted out to the general population – under the military rule of General Maxwell who took charge immediately after the surrender took place – that transformed the sentiment towards the Rising and its leaders and towards British policy in Ireland. The draconian repression unleashed created sympathy and then support for the rebels that the Rising itself had failed to achieve. Quickly it was British imperialism and its brutal repressive methods that were put in the dock of Irish and international public opinion.

George Bernard Shaw was one of the first to come out and condemn the approach of the British when on 9 May 1916 he said:

“I used all my influence and literary power to discredit the Sinn Féin ideal; but I remain an Irishman, and am bound to contradict any implication that I can regard as a traitor any Irishman taken in the fight for Irish independence, which was a fair fight in everything except the original odds my countrymen had to face.”1

By 12 May, less than two weeks after the Rising ended, 15 of the leaders had been executed (the last being James Connolly); 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested; 1877 were interned without trial and 144 were given prison sentences.2 Raids, harassment and curfews were commonplace experiences.

On the day of Connolly’s execution, Prime Minister Asquith visited Dublin and, perhaps sensing the growing alarm and outrage, called for the executions to stop immediately. The executions did stop, save for that of Roger Casement who it was deemed couldn’t be shown any clemency, and so was duly hanged in Pentonville Prison in London on 3 August. The ending of the executions by Asquith was already too little too late; consciousness was already busy being transformed.

It wasn’t just anger and outrage, however. These events served to reawaken an understanding that, at root, the relationship between Britain and Ireland was one of naked exploitation, imposed by brutal force whenever British imperialism deemed it necessary. In these circumstances, there was a sharp rise in a sense of injustice and national sentiment. The idea of a limited form of Home Rule, acceptable to many only weeks before, was now cast aside as support for complete independence rose substantially.

The Rising and the repression that followed also created knock-on situations that became focal points of activity and began to give some structure and organisation to the broad sentiment. There was the need to support those who lost family members during the Rising: mainly widows and of course many children, whose economic situation was turned upside-down, on top of the devastating personal loss they suffered. There was the need to support and campaign for those arrested and interned, which included those who were actually involved in the Rising and also those who were just rounded up by the British government’s iron-fisted response. Given the large numbers involved, these issues touched many families and a significant portion of the population, particularly in working-class areas.

These were immediate and practical situations that those from the different nationalist organisations, but also the general population, began to cohere around. In that process people also started to piece together their views and their more developed responses to the Rising, to its crushing and to the brutal reality of military rule.

Had Britain adopted a more measured response during and after the Rising, instead of a ferocious military clampdown, the speed and depth of the turnaround in attitudes to the Rising and British policy may have been somewhat different in its depth and character, but a transformation in consciousness would still have happened. It may have emerged over a slightly longer timeframe, but it would have emerged nonetheless. Before any shots were fired in the Rising, discontent was beginning to bubble about the war and the worsening social conditions it was inducing, both in urban and rural areas around the country. Just as it did in all other European countries around that time, this discontent would have burst to the surface in Ireland.

What the Rising did, or more accurately, what the brutal reaction of British imperialism to the Rising did, was galvanise the changing mood and act as a catalyst for the transformation of attitudes. Political consciousness was propelled forward, as was the sentiment for national independence. The heavy burden of the war was thrown off, and was replaced with a sense that change and great events were in the air. A new period of resistance and class struggle beckoned.

For social & national liberation – the two cannot be separated

By 1916 support for the war, which was already lower in most of Ireland than throughout Britain, had weakened further. Recruitment to the army had also fell considerably as the reality of war and militarism, began to impact on attitudes with the unprecedented numbers being killed and maimed. Initially the war had increased the numbers in, and stability of, employment, but by 1916 economic and social conditions were worsening significantly.

The conditions and issues that caused the great labour unrest in earlier years were re-emerging, but this time the discontent was also spreading to more rural areas. A crisis was developing due to the lack of land distribution to the rural poor and the insufficient incomes of farm labourers. 1916 also saw a 30% drop in potato production, which in turn was leading to profiteering. Prices had risen by 80% over the previous two years, while the highest wage increase had been around 10%.3

In normal times, mass emigration constituted an escape valve and somewhat relieved the pressure on Ireland’s weak economy. During the war, however, the movement of people was restricted, which served to build up economic pressure and undermine living standards. Social tension heightened throughout the country, both North and South. These local factors were supplemented with the growing general radicalisation that was an international trend, a consequence of the world war and the crisis in the global capitalist system. The unprecedented crisis facing humanity was preparing the ground for revolutions to sweep through country after country in Europe, particularly after the victorious Russian Revolution of October 1917.

Through their everyday experiences ordinary people understood what Connolly had asserted on many occasions – that the subjugation of people was not just on a national and political level, but was also economic and social. People knew that Britain gained economically from its interventions into and annexation of Ireland. They also knew that they directly experienced exploitation at the hands of Irish bosses. For working-class people in the South, getting independence from Britain was about attaining national rights, but it was also part and parcel of the struggle to transform their economic and social conditions.

The situation facing the working class in the North, specifically for Protestant workers, was more complicated. At that time the vast majority of the people in the North, including Protestants, would have considered themselves Irish or at least part Irish. At the same time the Protestant majority had an affinity toward, and social connections with, Britain. On top of this was the fact that the north-east of Ireland was an important component of the Britain’s industrial economy and was connected by production and trade to other industrial centres in Britain. While part of Ireland was still suffering economic hardship and repression at the hands of the British state, many communities in the North-East relied on industries that were completely integrated into, and very dependent on. the British economy and market.

Faced with this reality, it isn’t difficult to see why Protestant workers were suspicious of Irish nationalism; many feared that Irish independence would undermine their livelihoods through trade policies that an independent Ireland might adopt, which could cut them off from the British market and investment.

The nationalism of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) was sectarian, Catholic and focused on the needs of the emerging southern capitalist class. It had little regard for their economic or social situation, or for the working class in the south for that matter. A conservative, Catholic and capitalist-led movement for national independence would not appeal to the Protestant working class. If the mass of Protestant working-class people were to be won to the banner of Irish independence and away from the influence of Unionism, that could only possibly be done if the type of independence on offer would ensure that their economic position was enhanced, not diminished, and that their democratic, religious and cultural rights would be guaranteed. There was a strong labour tradition among Protestant workers, which would help to give a real material basis for the unity of the working class, Protestant and Catholic, on a radical platform. The emergence of the working class as the most powerful social force in Irish society in the first years of the 20th century brought with it the potential to overcome religious and sectarian division and to resolve the national question through socialist independence.

After the Rising, discontent at the conditions of capitalism and war really began to escalate all over Ireland, preparing the way for an explosion in the years ahead, which included a radicalisation and a new broad interest in socialist ideas. In the south, the unrest was dovetailing with the awakening of a strong sentiment to fight for national independence. The working class’ social and national aspirations were completely intertwined and interconnected. In the north, the discontent and radicalisation (and the strikes and movements that they generated) went in tandem with the rest of the country, as well as being influenced and affected by developments in Britain. However, at the same time, the movement for national independence being led by conservative forces meant that the Home Rule issue and the national question would act to undermine the potential unity of the working-class movement, North and South.

Would the new movement for national independence and freedom that was emerging after 1916 be fundamentally different from the narrow and conservative Irish nationalism that was dominant for years? Would it understand the importance of challenging the social subjugation of the working class and the rural poor? Would it also fight for a break with capitalism and landlordism? Would it understand the fears of the Protestant working class at the prospect of Home Rule and independence?

Alternatively, was it up to the labour movement to take the lead on the national question, as well as fighting to defeat the social and economic exploitation of capitalism? More than any other force, the labour movement had the capability to unite all working-class people – the majority in society – regardless of religion, gender or race. Could the labour movement take full advantage of its unique position and build a mass working-class movement for socialist change that could also free Ireland from the control of Britain?

Labour rises first & fast

The labour movement recovered first after the events of Easter 1916; strikes took place within a matter of weeks. The concrete and difficult conditions were forcing people to act. The renewed potential allowed the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) to appoint and send organisers out to build anew. On 5 August 1916, the Dublin Standard Post commented on the “well-marked revival of the Labour movement”.

As well as in the urban areas, activity expanded in small towns and rural areas where the situation for agricultural workers was becoming extremely acute. There was a shift of agricultural workers away from land associations in favour of trade union organisation and militant methods of struggle. The expansion of the trade unions by the mass recruitment of agricultural workers was to become a key component of the mass radicalisation that exploded in the years ahead. Actions and strikes on wages achieved major successes and further emboldened the movement. By the middle of 1917 the ITGWU, which the authorities and the bosses had vowed to smash, was accepted as a fact of life.

In the middle of all this, the workers’ revolution in Russian took place. This was the charged context in which workers began to flock once again to the labour and trade union movement. There were 72 delegates at the Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC) conference held in Sligo in 1916. At the 1917 congress in Derry there were 111 delegates, representing a trade union membership of 100,000. However, in one vital area the labour and socialist movement was much weaker than before: in the calibre of its leaders. Connolly and Larkin were revolutionaries and workers’ leaders who always fought to build the movement and for a socialist vision. Tragically, Connolly was dead and Larkin was in the United States. While there were many outstanding organisers and workers’ leaders, the principle leadership of the movement, the likes of William O’Brien (General Secretary of the ITGWU) and Labour Party leader Tom Johnson proved incapable of fulfilling the role that history called on them to play.

A very early example where a lack of clarity resulted in a major lost opportunity – which could have seen the labour movement galvanise the turmoil immediately after the Rising and take a firm hold of the leadership of the emerging national movement – was demonstrated at the ITUC Congress in Sligo in 1916. Just over three months after the Rising, the Congress should have defended the Rising and the motives of those involved, and come out with a fighting strategy to resist repression and military rule – linking these to the struggle for social change. Instead, they simply remembered all those who had died since it last met. Incredibly, they were not prepared to draw a political distinction between the Rising and an imperialist war. It didn’t even demand the release of all political prisoners, many of whom where trade unionists.

Notwithstanding the serious deficiency in the leadership of the labour movement, such was the organic need for workers to organise that the labour and trade union movement was continually catapulted by the ranks to the front of the struggles in society. However, the lack political clarity and leadership meant that labour would never realise its full potential, and Ireland was to pay a heavy price for this failure in the years ahead.

A new Sinn Féin emerges

The repression and events that flowed from the Rising – the harassment, the arrests, the release of prisoners and the need for solidarity and support – threw up focal points around which what remained of the nationalist and military groups could come together and organise around.

The name Sinn Féin became knitted definitively into the mix. When secret or semi-secret groups organise an event, there is always a chance of confusion as to who exactly was responsible. In an illustration of the power of the media, even in those times, when the Irish and British media said that the Rising had been organised by Sinn Féin, a small party led by Arthur Griffith (some referring to the Rising as the “Sinn Féin Rising” even though Griffith and his party had no involvement), this had an effect on popular consciousness and understanding. Establishment and military figures had labelled it a ‘Sinn Féin Rising’ to try to dismiss it and its participants as being unrepresentative and of the fringe. So in a sense it was by accident that Sinn Féin’s renown and popularity grew in tandem as attitudes changed to the Rising itself. United Irishman, a monthly publication of Sinn Féin at the time, became a weekly publication by September, an indication of the new interest and momentum.

When Lloyd George took over as Prime Minister in December 1916, as a gesture he released 600 prisoners from Frongoch in Wales and more from Reading jail. The enthusiastic welcome home the prisoners received just before Christmas registered how fundamentally the situation had changed compared to immediately after the Rising. This was another opportunity to mobilise and build and that, combined with the release of many experienced republicans, served to give additional strength to the broad national movement that was developing. By the middle of 1917, all those involved in the Rising had been released. There was growing support for a struggle for national independence and potential momentum for a movement, if one could establish itself in a form that the public could get involved with. Notwithstanding the potential, there was also disorganisation, confusion and turmoil in the aftershock of the Rising and its military failure.

In line with the tradition in the nationalist movement, there were military groups or organisations (or what remained of them) like the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), but there wasn’t an established political party or movement in the public eye advocating change or reflecting the changing mood and consciousness on the national and social questions.

The Redmondite Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) still existed, but its conservative history and role rendered it obsolete and irrelevant in the new political climate. They were associated with a compromising approach to British policy and were decisively undermined by the brutal military rule that was imposed. However, on top of that, their focus and interventions in Westminster were increasingly seen as worthless. When during the conscription crisis of April 1918 they withdrew from Westminster this was too little too late, and in fact only reinforced the abstentionist stance of the emerging nationalist movement. Later when the votes were finally counted in the 1918 general election, while they won some seats in the North-East, the IPP was effectively smashed as a force.

At the end of 1916 a by-election was announced for the North Roscommon constituency, with polling day set for 3 February 1917. This by-election afforded, at the very least, an opportunity to test public feelings. Different factions in the republican and nationalist movement considered their options.

Arthur Griffith tried to get Eoin MacNeill established as the candidate to challenge the IPP. Understandably, for those who were involved in or associated with the Rising, Mac Neill was unacceptable given his role in calling off the Volunteer actions for Easter weekend. Count Plunkett, the father of Joseph Plunkett (one of the signatories of the Proclamation), was pushed by elements in the IRB. Other groupings, and the likes of Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin, were forced to come around and support his candidacy given the direct connection he had to the Rising through his children.

In what amounted to a political earthquake, Count Plunkett won the By-Election easily, beating the IPP candidate by 3,003 votes to 1,708. Clearly, support for the IPP was evaporating.

The victory was not just down to changing views on the national question. The vital social question of land was also essential to Count Plunkett’s success. He used the slogan of “Land for the People”, and people voted for him and the nascent national movement in the expectation of action on the land question, as well as on national policy. Taking his election as an endorsement, the conacre war soon erupted in the constituency with cattle drives where hundreds of protesters seized land in an attempt to distribute it.

As broad consciousness was changing, the potential for a force to emerge into the political vacuum created by the collapsing base of the IPP was becoming very clear. New by-elections came along and more victories followed. 1916 prisoner Joseph McGuinness won the By-Election in Longford in May 1917 and DeValera won in East Clare in July. In August, Sinn Féin’s W. T. Cosgrave won the By-Election in Kilkenny. At this point, standing a candidate with a direct association to the Rising and agitating on the land question were a powerful combination. Other by-elections came and additional victories were also secured.

Count Plunkett’s victory in February indicated the potential, but even after that there wasn’t a cohesive entity capable of maximising the gains and pulling a movement together. With this in mind, Count Plunkett organised a convention on 19 April 1917 in the Mansion House in Dublin for the different organisations and communities to send representatives to. Two thousand people, including the various strands of the nationalist movement, attended the convention. One of the issues discussed, which caused significant argument, was whether there should be a movement in which the different groups continued to exist in an overall federal structure or umbrella, or whether there should just be one new organisation to which everyone belonged. Agreement wasn’t possible at the convention, so a committee was established to come back with proposals. The committee, titled “Organising Committee for the National Organisation”, was given six months.

However, the issue was decided for them very quickly. The name Sinn Féin was already out there and had been propelled into the public consciousness by the media as being responsible for the Rising. It became clear that this was the banner that people were gravitating towards as Sinn Féin began to grow exponentially and so events determined that the different forces would cohere under the Sinn Féin banner. Sinn Féin became transformed, bearing little or no relation in 1917 to the small party established by Arthur Griffith in 1905, except in name.

On 19 May 1917 the Sinn Féin publication Nationality reported that 27 new Sinn Féin clubs had been established.4 In June more prisoners were released from Britain and arrived back in Ireland. Again this acted as a focal point for mobilisation and building. In the week after their release it was reported that 80 new clubs were established. The 4 August issue of Nationality reported 38 new affiliations, while on 11 August another 58 were reported. After the by-election success in Kilkenny, the 28 August issue reported that 104 new Sinn Féin clubs had been established. As a further indication of the size of the clubs, or Cumann, the police in Sligo reported a tripling in size of Sinn Féin between June and July – from five clubs with 283 members to 15 clubs with 773 members. By September it had more than doubled again to 32 clubs and 1,747 members.5

Another event in September helped the movement grow but also demonstrated how much it had already grown. Thomas Ashe, originally from Kerry but based in Dublin, was very much a leading republican and played a central role in the conflicts in North County Dublin and Meath during 1916. He, along with 84 other prisoners in Mountjoy prison, went on hunger strike to demand treatment in accordance with “prisoners of war” status. Ashe’s death on 25 September, while in custody, as a result of complications connected to forced-feeding, had a major impact and his funeral brought Dublin to a standstill.

It is estimated that up to 30,000 walked behind the coffin and tens of thousands more lined the streets through the city centre up to Glasnevin Cemetery. It was reported by some that the ITGWU contingent in the cortege matched and could even have been bigger than that of the Volunteers. This was a sign of the growing national sentiment, but also of the rapid re-development of the organised labour movement. That such a demonstration could take place, including a gun salute at Glasnevin Cemetery, is illustrative of the fact that Britain was not in control of the situation.

Obviously, not everyone who came around was consistently active, but clearly by this stage Sinn Féin was well on the way to becoming a broad organisation with a mass base. The growth in the number of Sinn Féin clubs, but also their locations – often in rural areas – told the story of the crucial importance of land hunger to the development of Sinn Féin. Politically, the rural poor gravitated to Sinn Féin in the belief and expectation that they would fight for better incomes and for land for the poor. Sinn Féin activists on the ground organised land agitation because it was a crucial issue. At the same time they knew that this would help shift the support of many people from the IPP to Sinn Féin. However, such activities were inevitably going to create conflict with the larger farmers and ranchers, who in turn petitioned Sinn Féin about their concerns and opposition to this unrest.

Michael Hopkinson pointed out in The Irish War of Independence:

“The post-Rising Sinn Féin and Volunteer revival initially went hand in hand with agitation on the land question, caused by the absence of emigration during the World War years as well as the repercussions from previous land legislation, which had worsened income differentials within farming communities. In the western counties much of the popularity for advanced nationalism was related to land hunger, and Sinn Féin activists participated in cattle drives on grazier land during 1917 and 1918. Michael Brennan, the major IRA leader in East Clare, soon warned of the divisive effects of agrarian agitation and his attitude was in line with that of GHQ. British military and police sources were convinced that the spectre of Bolshevism lay behind political protest and failed to see how conservative the Sinn Féin movement had become.”

When push came to shove, the leadership of Sinn Féin was hesitant and conservative on the land issue, but clearly that reality was obscured as much as possible so that the land issue could still be a focus for their political agitation and source of growth. Members of the Volunteers were not forbidden from involvement in land agitation, but on 2 March 1918 an order was issued saying that if they did participate they did so in a strictly personal capacity.

Conventions for Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers were set for October 1917. The relationship of the military to the political wing of the growing movement was not fully clear and would remain as a constant and important issue for years to come. The IRB still operated within the broad Volunteers though not as cohesively as before. Soon the name Irish Republican Army (IRA) would emerge and begin to replace the title of “Volunteers”, particularly during the War of Independence. On the surface, at least some cohesion regarding the military and the political came from the conventions, as DeValera was elected first as President of Sinn Féin and then when the Volunteers met, he was elected President of that too.

While large numbers of ordinary working-class people were becoming part of or supportive of Sinn Féin, the class make-up of Sinn Féin in terms of its political position and its leadership was not reflective of the working class. Likewise, the wealthy and privileged establishment was not represented. The background or profession of those elected a year later and who made up the first Dáil is illustrative of the middle-class nature of the emerging leadership of the nationalist movement. Of the 69 Sinn Féin members elected as MPs in 1918, 65% were from professional backgrounds or involved in commercial enterprises. Thirty-one were professionals, including seven teachers and nine journalists. Five more were full time officials in nationalist organisations and a further 18 were involved in commerce, including a large number of shopkeepers.6

Key themes emerged in Sinn Féin policies and approach, though confusion and some differences, reflecting the broad base of the party, also remained. By now MacNeill had been brought back in on the insistence of DeValera,which indicated a conservative position both politically and militarily. It certainly indicated that DeValera, at least, didn’t favour another 1916-type uprising. Many also recognised the difficulties and the dangers in such an open confrontation with the British state. There wasn’t clarity regarding a military policy and the guerrilla tactics that were used at a later date were in many instances stumbled upon, rather than part of a worked-out plan.

In terms of political approach and objectives, abstention – not taking seats in Westminster – was a core position. The broad outlines for action included “to make British rule in Ireland impossible”, while declaring and taking the steps to build an Irish Republic. The objective of convening a Constituent Assembly in order to obtain a democratic mandate for action from the people was adopted. DeValera in particular also stressed the importance of international recognition of a Republic, particularly from the United States. The Paris Conference in May 1919 was a focal point for such efforts.

As 1917 came to a close, just a year and a half after the republican and nationalist movement had been scattered in the immediate aftermath of the Rising, a new movement, infused with fresh forces from a stirred population existed under the leadership of the new Sinn Féin. At first the name Sinn Féin was propelled into the new political vacuum by accident, but soon it rose to political dominance through a series of spectacular electoral successes and by the start of 1918 it had secured a mass base of support. Before the Rising, Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin had no more than one hundred members. Now, according to some reports, this new Sinn Féin had up to a quarter of a million.

The speed of growth of Sinn Féin was reflective of the radicalisation that was taking place in society. There was active participation across a broad spectrum – a new explosive movement on the land question and widespread industrial action. Sinn Féin had successfully captured the political space and while people looked to it as a mechanism to fight for national freedom, many of those who also hoped that Sinn Féin would address the burning issues affecting the rural poor and the urban working class would be disappointed.

Labour demonstrates its power & makes a challenge

The threat of conscription hung over Irish society like the Sword of Damocles since it became clear that the war was not going to be over in matter of months. This issue dominated the early weeks and months of 1918 in particular. Not long after the German army broke through their lines on the Western Front, the British Government introduced a Bill to the Commons on 9 April to establish conscription for Ireland, and passed it a week later.

The Lord Mayor of Dublin convened a meeting with representatives of groups and parties, including Sinn Féin and the trade unions, to discuss opposition to the measure and a broad Anti-Conscription Committee was established. A pledge to oppose conscription was launched with the support of the Catholic clergy who gave permission for petitioning to take place outside the Sunday masses. Many other actions by organisations and activists also took place. However, the single most decisive blow struck against conscription was the general strike organised by the labour and trade union movement, which happened on 24 April.

From a quickly convened conference on 20 April, within four days the Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC) pulled off a huge show of industrial power, with the first general strike in Irish history and a complete shutdown everywhere except in the North-East, where the action wasn’t organised. Thousands and thousands of workers on picket lines around the country sent shivers down the spine of the British establishment. If they proceeded with conscription, they would face a working-class movement the like of which they couldn’t have contemplated in their worst nightmares. They vented their anger by increasing repression but they were forced to retreat, and the cabinet took the decision in May to abandon conscription in Ireland.

The Labour movement had just struck the heaviest blow against British rule in Ireland and it set off a new strike movement that continued for the next two years. With victories under its belt in relation to the wages movement and conscription, Labour leaders O’Brien and Johnson, and the labour movement generally, were in a very strong position to again vie for the leadership of the movement for national and social liberation and to put the prospect of successful revolutionary change on the agenda.

“Labour Must Wait”

Labour could have tried to connect the day-to-day issues – the daily hardship and oppression – with the need for socialist change; organising the Labour Party on a proper basis, as a living force in every union and community, and in the process winning mass support in society. A key way of achieving this would have been to stand in elections and use the campaigns and any positions won as a platform.

The last general election had been held in 1910 and now one was in the offing and not long after the general strike Labour declared it would stand in that election. However, unfortunately little practical preparations were made to back that decision up. Sinn Féin had already developed a powerful electoral position, having taken the initiative at an earlier stage. They did not want Labour to stand precisely because they recognised that the labour movement had a tradition and a base and could be, particularly off the back of its victory in the general strike, a significant threat to its predominance. They began to exert pressure on Labour not to stand, saying that they supposedly represented the whole nation, whereas Labour represented a sectional interest; that Labour should stand aside and allow Sinn Féin to maximise the vote and mandate for independence.

It was vital that the labour movement follow up on the general strike and stand in the election in order to try to step into the leadership of the national struggle and imbue it with a real radical and socialist content. Undoubtedly doing this would have been difficult given the mood for getting the Irish Parliamentary Party out and the momentum that Labour had allowed Sinn Féin to build up. It would have necessitated a skilful struggle against Sinn Féin, exposing the limits of its conservative approach.

In the short term, even if Sinn Féin won the subsequent election, a marker would have been put down of a political alternative when people experienced disappointment because of Sinn Féin’s approach. The basis would have been prepared for a sharp shift to the left and towards a labour and socialist solution to the national and social questions. Even as late as August, the ITUC reaffirmed at its annual conference in Waterford that it would stand and it formally changed its name to the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (ILPTUC) in preparation. It also declared its support for the Russian Revolution. Unfortunately, neither position was really acted upon or taken further.

Sinn Féin continued to exert pressure by saying that they would stand everywhere to ensure a full commitment to abstentionism was presented to the electorate. That was a direct challenge to Labour and a reference to the fact that Labour’s position to boycott Westminster was qualified, i.e. that they would boycott Westminster as long as there was a war.

There is no doubt that Labour was under serious pressure, including from ordinary people, to step aside in order to ensure that the vote against the IPP and Westminster, and for independence, was maximised. However, such was the base of the labour movement that if they had insisted on the need for Labour representation and a left alternative (particularly if they had the clarity to publicly adopt a full abstentionist position, which would have been completely justified given the struggle and consciousness that was developing, and thereby undermine a key plank of Sinn Féin’s attack), it is entirely possible that they could have forced Sinn Féin to step aside in a number of constituencies. At least in this way there would have been Labour representation in the First Dáil. In a drastic mistake, however, the labour movement did not stand in the independent interests of the working class.

The crucial point was that there was confusion in the Labour leadership and the movement. There wasn’t an understanding of the urgent need to step onto the political plane in a real way and lead a socialist struggle for national independence. Some in the Labour leadership believed that Sinn Féin should be allowed to lead the national movement. O’Brien had campaigned for Sinn Féin in one of the by-elections and Johnson actually assisted Sinn Féin in the first Dáil by drawing up texts for the Democratic Programme. The hesitation about stepping into the political arena was also affected by the influence of syndicalism in the movement, where many activists focused overwhelmingly on organising and mobilising the industrial power of the working class as the means for change, rather than also focus on the need for a political struggle, including fighting in elections.

The executive of the ILPTUC decided in September that it should withdraw from the general election. A special conference was convened on 1 November and this position was forced through by 96 votes to 23. The proposal to withdraw Labour from the general election was made by Tom Johnson, the Labour Party leader. With this act, the leadership of the labour movement allowed Sinn Féin to claim the mantle of the undisputed political leaders of the national struggle.

Election success – but can the IRA beat British imperialism?

The general election took place on 14 December 1918. The main contenders were the IPP, the Irish Unionist Party and Sinn Féin. The Labour Party stood aside, though some independent labour candidates did stand in Belfast and did well in the circumstances, on average polling 22% in the areas where they stood. The overall outcome of the election was a decisive victory for Sinn Féin. Of the 105 MPs to be elected, Sinn Féin won 73, the Unionists won 26 and the IPP won a paltry 6 seats – mainly based in the North East, down from 73 in 1910. In the southern part of the country (what became the 26 counties) Sinn Féin won 68% of the vote, compared to 48% overall.

Sinn Féin obtained 474,963 votes; the Unionists 283,104; the IPP 226,657 and Independents 28,214. Sinn Féin candidates were declared elected in 25 seats unopposed as a result of the IPP’s inability to stand and Labour’s decision not to stand. Hence figures above understate the votes that Sinn Féin would have received if there had been contests in each constituency. As Labour didn’t stand, the votes also don’t show the strong political potential for Labour in society overall. The decision of Labour not to stand should also be put in the context of the electorate being massively extended in 1918, by well over a million new voters. Eight hundred thousand of these were women and it was the first occasion on which they could vote.7

While Sinn Féin was allowed to stand, there was ongoing repression against all separatist groups and parties. A consequence of this unusual situation was that while Sinn Féin stood in the election, the bulk of their new MPs (43) wouldn’t have been able to take their seats in Westminster, even if they wanted to, as they were in prison. Of course their policy was abstention from Westminster. Some in the British establishment naively thought it likely that they would succumb to the allure of the big salaries. Sinn Féin used their crushing victory in the election, achieved on the basis of abstentionism, as their authority to set up a parliament in Ireland. So instead of becoming MPs, the Sinn Féin representatives elected first became “Deputies” and then “Teachtaí Dála” or TDs, in Dáil Éireann when they met collectively to form a new parliament.

There were some initial private meetings but the formal convening of the first Dáil took place on 21 January 1919 in the Mansion House, Dublin. A large crowd gathered outside to witness the occasion. The proceedings were not interrupted by the state, which had to be mindful of the public mood. There were 27 deputies present. The business on the day included the declaration of an independent republic with a formal written Declaration of Independence that the deputies pledged allegiance to, the election of Ministers and the election of the delegates for the Paris Peace Conference – as well as a message to the free peoples of the world which called for Ireland’s independence to be vindicated in Paris.

Unlike 1916, where a relatively small number of combatants made a proclamation, this time on the basis of winning a majority of the popular vote in an election called and administered by the British state, a republic was declared and a Dáil, a government and a cabinet were established which claimed responsibility for the jurisdiction of Ireland in direct conflict to the British controlled administration in Dublin Castle. The battle lines were being drawn for an inevitable showdown.

The contending forces

Sinn Féin didn’t have a detailed battle plan, though clearly victory in the election and the establishment of the Dáil propelled the struggle against the British occupation of Ireland into a completely different phase.

As they saw it, they had achieved the objective of convening a Constituent Assembly, giving them a democratic mandate to constitute an independent state. The democratic mandate was also important in terms of credibility in approaching governments around the world. International recognition, if achieved, would increase pressure on the British Government. For now, they would push ahead and try to operate a government, try to construct a legal basis for its operations as well as an alternative system of justice to rival and challenge the one Britain operated in Ireland – a counter-state.

Following on from the vote in the general election, the hope was that people would give their allegiance to the structures of the new Irish Republic and boycott those of the British administration in Ireland. They aimed to create facts on the ground through building new state structures. At the same time they wanted to chip away at the position of British rule, including by military means, and hoped that this would force British imperialism to withdraw, or make a deal at some point. The British establishment would undoubtedly resist the outcome of the election and these tactics, and repression and armed confrontations would be sure to follow, and so had to be planned for. However, exactly what form the military campaign that the Volunteers, later formally called the IRA, would take wasn’t clear.

In addition, if the alternative government was to be meaningful and not just symbolic, they would need real and substantial resources in order actually to implement policies and change the lives of people. If they weren’t able to implement and demonstrate real change, that would weaken their chance of getting the type of mass, active support and resistance that was clearly necessary to force the might of British imperialism out of Ireland.

For the British establishment, the situation in Ireland was very serious and one which they were never going to take lightly. The potential loss of Ireland would mean a significant economic blow, especially considering that the north-east of the country was an important part of its industrial backbone, connected to the industrial base and trade with Scotland and the north-west of England. Ireland was of strategic military importance as a gateway into the Atlantic but also as a gate for other powers to attack Britain. The loss of Ireland would also have been a huge blow to the British Empire, which still covered a huge portion of the globe. Undoubtedly it would have led directly to the boosting of separatist and independence struggles in many parts of the Empire, including the likes of India, Egypt and South Africa.

There was no question about it; the British establishment would resist moves toward Irish independence, and certainly any moves toward radical or socialist change in Ireland, with brutal force if necessary. They had also shown on many occasions that they were prepared to foster and use naked sectarianism to divide Protestant from Catholic, and they were prepared to do the same again. They didn’t necessarily need pretexts for their divide-and-rule policy, but they were often given opportunities and pretexts by the sectarian rhetoric and actions of the elements of Irish nationalism directed against Protestants and by unionist sectarianism. They would be given more such opportunities in the years ahead.

The Dáil & the Democratic Programme – a promise of change

The Democratic Programme of the first Dáil was discussed and passed in January 1919. Some points in the document are significant though they were limitedly acted upon or fought for. However, what the document didn’t say, or to be more precise, what was taken out of the Programme, was just as significant.

Sean T. O’Kelly wrote the Programme on the basis of a draft from Labour leader Tom Johnson. Similar to the Proclamation, the Democratic Programme used vague language declaring “the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destines.” However, it also said that all right to private property must be subordinated to public right and welfare, a development on the Proclamation.

Yet the following clause, which paraphrases Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, was contained in Johnson’s draft but was then completely deleted:

“The Republic will aim at the elimination of the class in society which lives on the wealth produced by the workers of the nation but gives no useful service in return and in the process of the accomplishment will bring freedom to all who have hitherto been caught in the toils of economic servitude.”

It is reported that O’Kelly deleted this section after strong objections from Michael Collins and the IRB.8 So the Democratic Programme was cut or edited to remove a commitment to uproot capitalism, something that would have been necessary to transform the social conditions of the majority.

In reality the Democratic Programme was wholly rhetorical and this was exposed when a representative, Alderman Kelly, asked on 11 April 1919 in a public session of the Dáil for proposals to allow the implementation of the Democratic Programme. DeValera replied, “it was clear that the democratic programme, as adopted by the Dáil [just over two months previously], contemplated a situation somewhat different from that in which they actually found themselves.”9 DeValera went on to say that they were occupied by a foreign power and that he had never made any promise to Labour; that while the enemy was within the gates, the priority was to gain possession of the country.

DeValera knew well enough the difficulties that existed when the Democratic Programme was being passed and extolled. But his latter point is illustrative of his and Sinn Féin’s approach: instead of standing for radical measures that could transform people’s conditions and challenge the rule of British imperialism, the existence of British imperialism in Ireland is used as justification for why radical polices couldn’t be implemented.

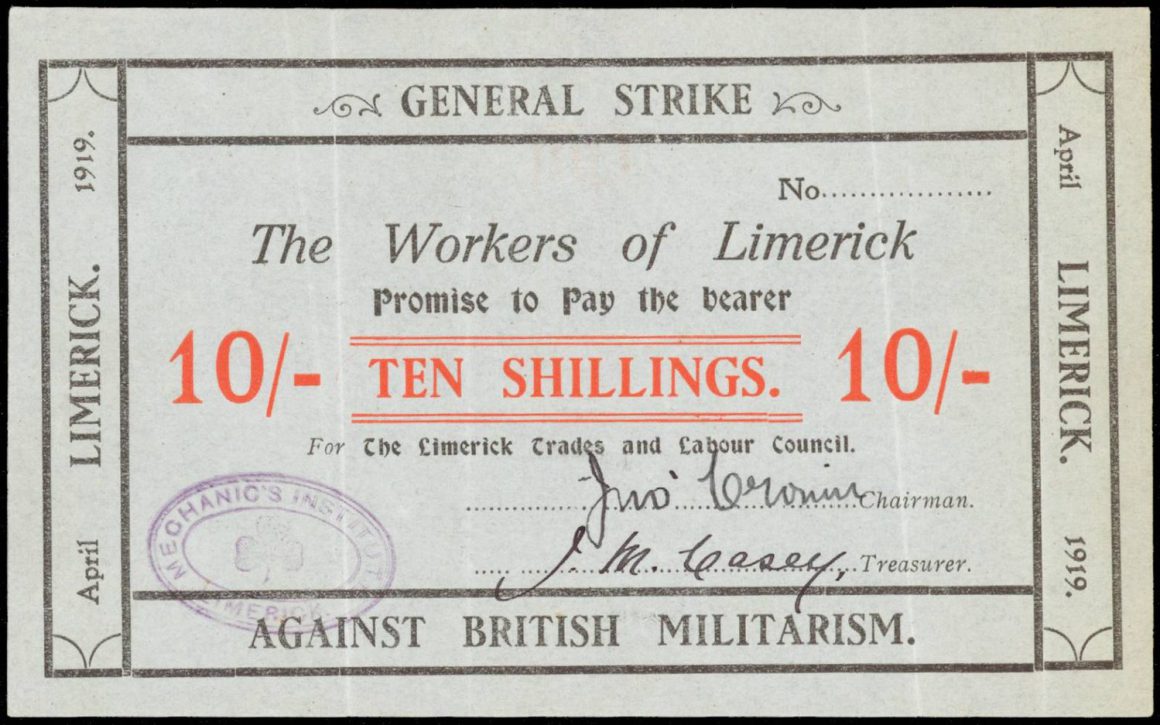

Four days after DeValera made this statement the working class of Limerick demonstrated that such a struggle for social and national liberation was indeed possible when they mobilised and expelled the British military out of the city and set up the Limerick Soviet. The Soviet controlled and reduced the prices of key goods and printed its own money. If the same approach had been adopted on a national level, the struggle for national and social liberation could have been given a huge impetus and British Imperialism could have been confronted with a powerful force the likes of which it had never faced before.

Another example of the lack of focus on the key issues facing the working class – in the North-East in particular – was when the Dáil didn’t discuss or support the historic Belfast Engineering Strike which erupted soon after the Dáil was established. The strike, practically a general strike in Belfast, lasted from late January to early March. At its height, 20,000 were on strike and a further 20,000 workers were affected, with virtual workers’ control of Belfast City.

Cathal Brugha gave a prominent speech on 31 January at a Sinn Féin concert to celebrate the election victory and there was no mention of the Belfast strike. It was probably the single most significant dispute since the Lockout, yet it didn’t warrant a mention or a motion of support from the Dáil. It is difficult to conclude that this omission was the result of anything other than a sectarian and hostile class view.

Yet another example is from the latter part of 1920. There was some speculation about the possibility of discussions between the Irish and British governments. The Financial Times (15 September 1920) interviewed Arthur Griffith and Eoin MacNeill on 15 September, as there were concerns among investors of what they could face from a possible Sinn Féin government in the event of some form of greater independence. The interview may shed further light on the non-implementation of the Democratic Programme. They said, “We have no desire to harm investors in the least…it would be foolish on our part to do anything to alarm them.” Griffith went on, “You can tell your City men, that they have nothing to fear in the way of confiscation or unjust discrimination.”10

The hopes that US President Woodrow Wilson could be forced into some form of recognition of the Irish republic, or that he might initiate some process towards recognition because of Irish-American pressure, were ill founded. Of more importance to Wilson, who represented the interests of US imperialism, was the post-war relationship with British capitalism and so Sinn Féin’s delegates were not admitted, and nor was the Republic recognised, by the Paris Peace Conference.

Attempts to construct a counter-state

In addition to weekly meetings of the cabinet and regular sittings of the Dáil at a time of increasing military rule, Sinn Féin and the Volunteers also moved to try to undermine the British-administered state in Ireland, its court system and local government, and establish Irish Republican versions of the same. Initially the British intelligence services considered the attempts by the republican movement to create a counter-state to be a failure. However, in the latter part of 1919 and the first months of 1920, their own system of administration and law began to unravel as Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks in more remote areas, as well as in some towns, were progressively abandoned, increasingly affected by the campaign of ostracism, boycott (which was formally endorsed by the Dáil on 11 April 1919) and attacks.

Raids and attacks on barracks became widespread as the guerrilla campaign of the IRA commenced. The burning of tax offices in April 1920 meant that, from then until the emergence of the “Free State” in 1922, income tax wasn’t collected in most of the country. In August 1920 official figures showed that over 550 RIC officers had resigned from the force in the previous two months. Such developments were devastating to a force with a total of 9,500 officers, meaning the RIC was incapable of effectively policing the state. By the middle of 1920 the existing British-sponsored court system couldn’t function either. They had been undermined by the popularly supported boycott. This was supplemented by pressure exerted by the republican movement on people not to take cases to court, or for witnesses or jurors who had been summoned not to attend.

With the demise of the RIC and the power of the courts, in many areas Sinn Féin and the IRA were the only authority and there was often support for their intervention to resolve issues. The 1880 Arbitration Act allowed for a third party to legally mediate between parties and initially this was used to underpin the establishment of courts in some areas. In the summer of 1919, Arbitration Courts had been decreed by the First Dáil. From early 1920, Republican Courts began to appear in different areas and then in June the Irish Republican Police were formed to help administer the courts and local justice. A national scheme of courts was also initiated in June with the hope of having it in place by the autumn.

The court rules established in the West Clare parish and district court in January 1920 began to act as a model for the establishment of the other courts. Soon courts were given the power to compel participation and to impose binding and compulsory decisions on the parties. Clearly there was also a desire for justice on many issues given that the denial of a meaningful and democratic justice system was widespread. This created an enthusiasm for the Republican or Dáil Courts and there was an expectation that these courts could be a positive mechanism to ensure some economic and social justice was achieved.

Inevitably conflicts of class interest were going to come before courts, given the burning difficulties that the poor were experiencing. For Sinn Féin, maintaining the national unity and stability was more important than a sectional or a class injustice. Invariably that meant maintaining the status quo. In instances of class conflict the courts reflected the pragmatic political position of Sinn Féin, and tended to come down on the side of the haves as opposed to the have-nots, i.e. protecting the interests of business, big landowners and stability were prioritised over those of the rural poor and working class.

Having pointed out how land owners had come to Dublin to beseech the Republican authorities to do something about the land agitation and cattle drives that were erupting in Connacht, North Munster and in West Leinster in the middle of 1920, C. Desmond Greaves writes in Liam Mellows and the Irish Revolution:

“The movement of the small farmer and landless men was seen, not as a means of fulfilling the Democratic Programme of Dáil Eireann, but as a ‘threat to the stability’ of the national movement to which the landlords did not belong. Arbitration courts were hastily summoned. A land bank was established to do the work which the Congested Districts Board was failing to perform. In one instance in County Mayo, where the local police were in disagreement with the decision of the Republican Court, Volunteers were brought in from Clare and Donegal, and twenty-four men had been taken as hostages before the tilling operation ceased.”

In The Republic, Charles Townshend writes:

“In April Sinn Féin announced that ‘anyone who from this forth persists in pressing a dispute will do so in the knowledge that he or she is acting in defiance of the wishes of the people’s elected representatives and [to] the detriment of the National cause’. Two months later the Dáil urged that ‘the present critical time’ was ‘ill-chosen for the stirring up of strife amongst our fellow-countrymen’. ‘All our energies must be directed towards the clearing out – not the occupier of this or that piece of land – but the foreign invader of our Country.’ So it decreed that ‘pending the international recognition of the Republic, no claims of [this] kind shall be heard or determined by the Courts of the Republic’.”

The RIC and the operations of the British courts had been undermined and damaged irreparably. But the alternative Republican Courts themselves weren’t securely established because of a lack of judges and the resultant large backlog of cases didn’t constitute a mechanism for tackling the continuing social and economic inequality and injustice.

Councils defy British authority

Electoral advances in January and June 1920 were the platform from which Sinn Féin also began to undermine the British system of local government. Sinn Féin performed well in the two different sets of local elections held in 1920. In January, which saw elections to municipal and urban councils, Sinn Féin, their allies and Labour became the majority in nine out of 11 municipalities, and in 62 out of 99 Urban District Councils. In June the same forces became the majority in 29 out of 33 County Councils. Like when the alternative courts were initiated, these electoral gains were achieved with hopes and expectations among many that they would lead to improvements in the crucial issues of land, housing and health.

Sinn Féin put pressure on the other forces, including Labour, to ensure Sinn Féin mayors or leaders were elected to as many councils as possible. The policy was to get the councils to recognise the authority of the Dáil. In Dublin, having had a majority since January, it wasn’t until May that the council recognised the Dáil, indicating that this policy wasn’t straightforward or easily implemented. A key problem was funding local government. If a council declared for the Dáil and the Republic instead of for the British-sponsored Local Government Board (LGB), their funding would be cut and the question of how the council would fund its important public functions and services was immediately posed.

In general Sinn Féin didn’t have an adequate answer for an alternative source of funding, particularly given that many people had in part voted for them with the hope of change and new improvements. Sinn Féin was challenging British authority in Ireland but it was not fundamentally challenging the reality that individuals and businesses owned the vast bulk of the wealth in society. That meant that a council declaring for the Republic might be beneficial for Sinn Féin in the political struggle against Britain, but on the other hand it could undermine the services that ordinary people got from the councils. Britain would withhold funding but Sinn Féin was not prepared to take the radical measures necessary to ensure that the wealth that existed could be used for the public good and to service the functions of the councils.

Sinn Féin’s piecemeal approach wasn’t capable of defeating the British state, and it meant that they didn’t have the power and resources to transform the lives of ordinary people. Their own objective was being undermined by their own limited approach. In fact this uneasy conflict over local councils and central authority was brought to a head, not by decisive action by Sinn Féin, but instead by the actions of the British Government when, in the summer of 1920, it demanded that all local authorities declare their allegiance to the LGB. Then, on behalf of the Sinn Féin Government, W. T. Cosgrave wrote to the local authorities on 12 August to demand they break all links with the LGB and recognise Dáil Éireann, which is what progressively happened, but still without a clear plan for local government on the part of Sinn Féin.

Military conflict escalates

However, connected to their problems with the RIC, the courts and the councils, a new British military offensive against the republican movement was launched. What became known as the War of Independence began with the attack in Soloheadbeg, South Tipperary, on the same day as the first public meeting of the Dáil on 21 January 1919. Two RIC men were killed in a gelignite attack aimed at securing weapons. The War of Independence grew in intensity as 1919 passed.

In the first period the British considered the disturbances in Ireland of a level that could and should be dealt with by the police force. However, in the Autumn of 1919, Britain began operating a policy of reprisals against local communities when their forces were attacked by the IRA. This started in Fermoy on 8 September 1919. The conflict escalated in the latter part of 1919 and the early months of 1920. The IRA attacked barracks on a wider scale than before and the intensity of the engagements increased. Other famous reprisals and sackings of towns undertaken by the notorious Black and Tans were in Cork City, Tuam, Trim, Templemore and Balbriggan, to name a few. Fifteen months in to the War of Independence things would escalate again.

Britain’s initial underestimation of the conflict formally changed in March 1920, when Black and Tans, a 7,000 strong paramilitary group, first appeared on the scene. The Black and Tans were made up in the main of demobbed ex-British Army servicemen. They were supplemented further with the Auxiliaries in July, which was made up of around 2,200 ex-Army officers. The Restoration of Order Act in Ireland was also passed in August 1920 and that strengthened military rule. As the year wore on, formal martial law was declared in many areas.

Early on the morning of Sunday 21 November, IRA men operating under instructions from Michael Collins raided a number of locations in the south and the north inner city of Dublin with the aim of striking a major blow against British intelligence operations. In total, fourteen men, including army, Auxiliaries and an RIC officer, were shot dead and another died later in what was deemed a highly significant and successful operation.

Later that afternoon, in a tense Dublin, British troops entered the surrounds and the ground at Croke Park during a Gaelic football match between Dublin and Tipperary. The intention was a revenge raid of the proceedings. In the process they opened fire for ninety seconds into the crowd who were watching the match. Fourteen civilians were shot dead and more than 60 others were injured. Later in the evening three IRA suspects were tortured and then shot in Dublin Castle, the authorities claiming they were shot attempting to escape.

While the events of Bloody Sunday were viewed as a success for the IRA and a shame for Britain, overall the IRA’s military campaign was in difficulty. In October 1920 some in the IRA expressed the view that there had been a shift in the balance of power in favour of the British. Charles Townsend states:

“Dublin District Command believed that there was a significant shift in the balance of power in late October 1920. Terence MacSwiney’s death ‘had a far-reaching effect in reviving confidence’ in the government’s firmness of purpose, and ‘a further deterioration’ of IRA morale was noticeable. Significantly, ‘for the first time ammunition was found abandoned by rebels,’ and several substantial ‘rebel arsenals’ were captured.”12

Unlike the impact of previous hunger strikes, the deaths of hunger striker Terence McSwiney in Brixton in London on 25 October and of two prisoners in Cork, notwithstanding the major public demonstrations that took place, were a blow to morale.

As well as Bloody Sunday, November also saw the British forces begin a series of executions. Between then and June 1921, 24 volunteers were executed, starting with Kevin Barry in Mountjoy Jail in Dublin on 1 November. Martial law was declared in multiple counties on 11 December, though the east and Dublin were left open, supposedly to allow for possible talks between the combatants.

The British Government had introduced the Government of Ireland Bill in late 1919 and was preparing to pass it as an Act in December 1920, while ratcheting up its use of force. This act contained two Home Rule Parliaments in two new states, as well as a Council of Ireland. That it contained two Parliaments in separate jurisdictions meant that rather than implementing Home Rule, in reality this was an act to impose partition. Partition between North and South was the backdrop throughout 1920 and it had a crucial effect on developments.

As they were intensifying repression, the British Government also held out for the prospect of talks in December 1920. Working through intermediaries, their insistence that IRA weapons must be handed in before talks could begin meant no engagement took place. The British had hoped that by intensifying the repression that they might be able to force Sinn Féin and the IRA into negotiations. After this failed, Britain continued to build the pressure, trying to squeeze Sinn Féin and the IRA even more in the first six months of 1921.

Most brutal & bloody phase

The War of Independence lasted a full two and a half years before a truce was agreed on 11 July 1921. But in the last phase, between January 1921 and the date of the truce, 1,000 people were killed. A staggering 70% of deaths occurred in the final fifth of the conflict. This is a graphic illustration of how brutal the final months were. Four and a half thousand were also interned during the same timeframe. The British forces were suffering from exhaustion and were under pressure and it is true that they weren’t able to completely eliminate the resistance of the IRA given the sympathy and support that existed in the communities. However, there was also no question that their renewed efforts had seriously weakened the capacity of the IRA.

When a new truce was offered, the IRA wasn’t in a strong position to decline. Their campaign was based on isolated acts of terror or guerrilla warfare tactics, but was removed from the active mass movement of the working class that had exploded, particularly after the general strike against conscription in April 1918. While there was sympathy and support, Sinn Féin and the IRA’s methods were not the most effective ways of conducting a struggle and weren’t powerful enough to be able to defeat the military might of the British state. The way that could have been achieved was not by limiting the political scope and active involvement in the struggle, but instead to embrace a struggle for full social, economic and political change by mobilising the mass of people, arms in hand.

Michael Collins summed up the situation in a letter to the Chief Secretary for Ireland. He wrote: “You had us dead beat. We could not have lasted another three weeks. When we were told of the offer of a truce we were astounded. We thought you must have gone mad.”13 Just before the truce was agreed, the IRA GHQ itself estimated that the IRA had only 3,295 rifles available to it.

They hadn’t gone mad, but believed that while they were experiencing difficulties, those facing Sinn Féin and the IRA were considerably worse. They were confident, having set in train a process towards partition, that they could get an outcome from negotiations which would in general safeguard the main interests of British Imperialism. The truce was agreed in July and quite quickly there were a number of meetings between DeValera and Lloyd George that outlined the possible parameters of negotiations and agreements. However, a number of months passed before serious negotiations took place in October. There was considerable back-and-forth between both the British and Irish sides and the Irish delegation reported back to Dublin in late November 1921, before returning to London in early December.

The British delegation included Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead, Austen Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. On 6 December, all the Irish members of the delegation, including Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, under pressure from the British delegation, signed a treaty. This was then brought back to Ireland where opinion on it was sharply divided.

Defeat inevitable under Sinn Féin’s leadership

The main issues of contention and division were as follows: Ireland would not be independent but would be self-governing as a dominion within the British Empire, with additional special conditions attached; the Treaty necessitated a repudiation of the Republic declared in the Dáil on 21 January 1919; elected parliamentarians were to take an oath to the new Free State, but this also included an oath to the British Monarch; and that Britain was to have access to “Treaty ports” around the country so that it could safeguard its own strategic interests. Crucially, the Treaty copper-fastened partition: The Northern Ireland state, created by the Government of Ireland Act, had the right to opt out and if it did so a boundary Commission would be established to draw the dividing line between the two states. Partition was anathema to many in the republican and nationalist movement and was central to many people’s opposition.

The cabinet voted by four votes to three to recommend the Treaty to the Dáil. The debate and discussion in the Dáil and in Irish society went on for some time, which suited the Pro-Treaty side. There was a break for Christmas and then the Dáil returned on 3 January 1922. On 7 January the Dáil voted for the Treaty by the narrow margin of 64 votes to 57.

Having held the initial discussions with Lloyd George, DeValera didn’t participate in the delegation, clearly knowing that the negotiations would be difficult from an Irish nationalist point of view. When it was brought back, he opposed the Treaty while Collins defended it as the best deal possible. The acceptance of the Treaty by the Dáil immediately undermined DeValera’s position as the leader of the nationalist movement and he called a vote in the Dáil on his position as President of the Republic. He lost the vote by the even narrower margin of two votes. The Treaty was passed and the nationalist movement was now profoundly split.

According to Michael Collins, Lloyd George threatened “terrible and immediate war” if the Treaty was not accepted. The situation in Ireland had taken a toll on the British establishment both in terms of resources and political capital. There were 50,000 British troops in Ireland when the truce had been agreed and the British Labour Party, labour movement and socialist activists were engaged in significant public campaigning throughout Britain demanding peace for Ireland. However, precisely because the social and class stability in Britain, as well as the future of its Empire, were directly affected by events in Ireland, if necessary, Britain would have been prepared to resume the conflict, as well as continuing its policy of divide-and-rule in Ireland.

That didn’t prove necessary because the Pro-Treaty side won the day, in part by feeding off the weariness of people after many years of conflict, but also because the nationalist anti-Treatyite wing of the republican movement wasn’t able to point out a clear alternative route to how independence could be achieved. However, once the delegation signed the deal and a split was inevitable, the nationalist movement’s capacity to resume the conflict and wage a struggle was fundamentally weakened. This reality had an effect. The Anti-Treaty side had a majority of the volunteers and fighting units, but now the challenge was substantially greater than before. Weakened, could they defeat not only Britain, but the Pro-Treaty side too?

If the Treaty had been rejected, it’s clear the nationalist movement would still have suffered some form of division. During the six months of truce they had been able to replenish their supplies, but clearly a desire for peace and normality had developed, and the military routine had been broken. This meant that there would have been difficulties to any campaign that the IRA had waged. More British military atrocities in Ireland would have provoked new mobilisations and demands for peace in Britain, although the rejection of the offer would have been used by the media and establishment to paint Sinn Féin, the IRA and the Irish people in a certain light. It is most likely that a resuming of hostilities would, sooner or later, have come back to a point where Britain would effectively overcome the nationalist movement and a worse deal could have resulted.

This outcome could have been different if the leaders of the nationalist movement or of the labour movement had tried to mobilise ordinary people themselves into the struggle (or if the mass of people themselves mobilised) against military rule, on the promise that national freedom would also mean an end to economic and social exploitation. Then British imperialism and capitalism could have been threatened. Mass movements and struggle of that kind against British imperialism and its military would have gotten even stronger support in Britain.

However, by 1922 the republican movement, and DeValera in particular, had demonstrated its complete inability to embrace the concerns of and to mobilise the mass working-class movement. By then, after a series of defeats, the pendulum of the movement and the mood was swinging in the wrong direction and a spontaneous upsurge from below to take on British imperialism was unlikely. In the end the republican movement affirmed the proverb that you don’t win at the negotiating table what you haven’t won in the battle. The deal was a bad deal and a blow to the national aspirations of the Irish, but the reason wasn’t the personal weaknesses of the delegation. Sinn Féin and the IRA waged a significant battle over four years, but their conservative political approach and the tactics that they used were limited and were always likely to fall short of the power and strength necessary to defeat British Imperialism.

It is ironic that a real and living mass movement of the working class and poor was the dominant feature in Ireland over those same years. Sinn Féin, the IRA and nationalism in general, however, remained suspicious and fearful of the working-class movement.

Civil War

The Civil War grew out of tensions, stand-offs and skirmishes between pro and anti-Treaty forces in the first half of 1922. It passed a point of no return on 27 June when Collins eventually ordered the Free State forces to retake the Four Courts in Dublin, which had been occupied by Anti-Treaty IRA since the middle of April.

The first general election in the new Free State had taken place on 18 June 1922. In reality it was also a referendum on the Treaty, and the vote indicated that the broad population, who had striven again and again over the previous for revolution, now didn’t see any real chance for conducting a struggle for meaningful change. As a result, the Pro-Treaty faction of Sinn Féin received 239,193 votes and the Anti-Treaty faction received 133,864 votes (247,226 voted for other parties, including 132,570 votes for Labour).

With partition, the Treaty and then the Civil War that went on until May 1923. The process of revolution and potential change that had been signposted by the Easter Rising six years earlier had come to an end.

Why British establishment moved from Home Rule to partition

In the early years of the twentieth century the majority of the British establishment had come to support Home Rule for Ireland, led by the Liberals. An important wing opposed this, represented by the Tories. However, with the rising labour unrest in Britain, Ireland and throughout Europe, and in particular after the successful revolution in Russia, the British ruling class rallied and united around the need to stave off the threat of Bolshevism.

The 1916 Rising signified the start of a period of revolution in Ireland that continued for many years. The greatest events and highest point in this revolutionary process were between 1918 and 1920. Such was the depth and scope of that revolution and the mass movements that took place that a serious question mark was raised over the continued existence of capitalism in Ireland. In turn, a defeat for capitalism and British imperialism in Ireland would have placed change on the agenda in Britain itself. The nightmare scenario for the British establishment and its strategists was the development of a mass movement towards socialism in Ireland that would act as a catalyst for change not just in Britain but throughout the Empire.

The Treaty of 1922 went further in some respects than previous Home Rule propositions, but that was the small change that British imperialism was prepared to pay in order to avert the more fundamental threat of social revolution. Harold Spencer reported Lloyd George as saying the following in 1919:

“Ireland had hated England and always would. He could easily govern Ireland with the sword; he was far more concerned about the Bolsheviks at home.”14

The policy of Britain in regard to Ireland was to do whatever was necessary in order to safeguard the interests of British Imperialism. In 1919 there emerged not just a threat from Bolshevism at home, but in fact the more immediate threat of Bolshevism in Ireland. While the establishment were divided previously on Irish policy, by 1919 they were united. Partition of Ireland – the creation of two separate sectarian states – was the best way to try to divide the Irish working class between Protestant and Catholic, and derail the movement in Ireland.