By Rob Rooke, Socialist Alternative (sister organisation of the Socialist Party in the US)

“This is Telemarketing – Stick to the Script!” is the message shot at Lakekeith Stanfield (Get Out, Atlanta) who plays Cassius Green in Boots’ Riley’s toboggan ride of a first movie. However, Sorry To Bother You does not stick to the typically sanctioned Hollywood script.

Boots Riley, the unofficial leader of Occupy Oakland in 2011 and front man of the left-wing hip-hop band, The Coup, has directed his first movie, Sorry to Bother You, due for general release in July, 2018. The trailer has several million hits, with activists and fans eager to see if the movie meets expectations.

At the recent Bay Area premier, Riley spoke about the current wave of politicization in the Trump era and the rise of black cinema. He reminded everyone that movies didn’t create this wave, but, on the contrary, this increased interest in politics is inspiring film-makers. The director describes Sorry as an absurdist, dark comedy inspired by the world of telemarketing: the low paid world where Riley worked in his twenties.

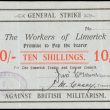

Riley completed the screenplay during the ebb that followed the Occupy Oakland movement. Oakland’s Occupy culminated in a general strike involving tens of thousands and was backed by a small number of unions, before it was brutally forced off the streets by police. Riley was connected with some of the workplace organizing drives that came out of Occupy, some experiences of which no doubt contributed to the movie.

Oakland, California

Sorry to Bother You is set in Oakland, California: home of The Coup and of the director. Its depiction rings true to life. The run-down buildings, liquor stores, graffiti; the roadways lined on both sides with the tents of the displaced. The movie navigates this dereliction on the one side, along with the soaring corporate high rise towers of Oakland’s skyline. It is onto this dystopian canvas that Sorry’s characters are placed.

Much of Sorry centers around the twists and turns that emanate from the cubicles of the telemarketing agency where Cassius “Cash” Green is hired. We laugh along with the workers and laugh out loud at the managers, at whom Riley’s script sends its daggers. Sorry talks frankly about real issues: rents, jobs, foreclosures. The problem of economic insecurity weaves in and out of the movie’s plot, as the characters make the limited and often harsh choices available to them.

Sorry pulsates along in a society where capitalism has been tweaked into its surreal twin, both conceivable and absolutely unreal. In this world, corporate America is unrestrained. Its media more horrendous, and its arrogance is magnified. In Riley’s dark magical realism a mega corporation gets to do whatever it wants, and it does. It is shocking and yet normalized in the context of the story.

Most of the reviews coming out of the movie’s exposure at the Sundance Film Festival have been positive. However, Riley has expressed his surprise that while the wild ride and bizarre aspects of the movie have been celebrated in reviews, none have written about the key central struggle in the film: the workers’ struggle for a union and their strike.

Worker Organization and Unionization

The characters of the movie live in precarious housing, eat Top Ramen and barely eke out a living, while the telemarketing agency they work for amasses a fortune. Sorry introduces Cassius Green, a young black man, into the workplace where Cassius learns to perfect his white voice on the phone and is soon promoted into the company’s upper echelons. His co-workers seek another route forward: union organization, and a defiant, prolonged strike. Sorry explores all the complexities of this rising conflict, anxiously, painfully and at times hilariously, until it is finally resolved in the film’s maniacal climax.

Cassius’ fiance, Detroit, is the moral and political backbone as well as heart of the movie. Along with the union organizer, she is grounded in the importance of solidarity, and generally ahead of the curve in foreseeing how Cassius’ journey will likely unfold. Despite Detroit’s foundational role in the movie, Sorry does fail the Bechdel Test in the absence of multiple leading women characters, which is an unfortunate weakness.

Sorry to Bother You is simply unlike anything out there. In its form, it is edgy and at times disturbing, but it is unique more so in its content. Its outlandishly spun story, at its core is about working people trying to find a way to solve their problems, individually and collectively. Like some other movies, it is not soft on the brutality, racism, and narcissism of capitalism, but Sorry does something different in current cinema. It points its finger toward self-organization, toward unions, toward strikes, toward mass picketing as a way forward. And it does not fail us by having liberalism riding in on the proverbial white horse to save the workers.

Boots Riley has made a film for our times, made more poignant with the current wave of strikes hitting America’s schools. Riley has referenced the poll that finds that a majority of millennials feel more connected to socialism and communism than capitalism. This is the audience of millions to whom this movie is aimed. It is not clear if Sorry will reach beyond that, to the mass audience it deserves, but many, many young activists around the country are counting the days until its release.

Sorry to Bother You is neither a movie constructed around product placement, like so many corporate movies, nor is it written as a blueprint for organizers or the anti-capitalist movement. It was written to unearth hypocrisy and unseat the powerful. Sorry does not leave us with Hollywood’s usual pessimism or its empty optimism. Its conclusion urges us on. Like it’s aggressive, driving soundtrack, Sorry captures the energy, spirit and willingness to fight. And we can only win if we fight.