National oppression & economic exploitation

Betrayal of Second International

The war & Ireland

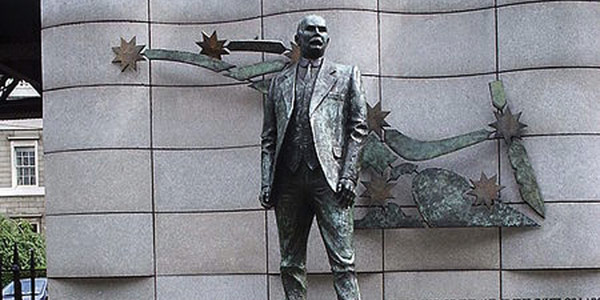

A heroic figure

James Connolly was Commandant General of the Dublin Division, Army of the Irish Republic and Vice President of the “Republic” declared in the Proclamation. When he continued his duties in the GPO after being wounded, Pearse, technically the most senior leader of the Rising, commented that Connolly remains, “still the guiding brain of our resistance.” However, Connolly was also the most dynamic force pushing for and ensuring that a rising actually happened.

James Connolly was a Marxist and believed in the necessity of socialist change in Ireland and internationally. Connolly himself accurately described the important but also limited goal behind the Rising in his last statement written on 9 May 1916, just three days before his execution.

“We were out to break the connection of this country and the British Empire, and to establish an Irish Republic. We believe that the call we then issued to the people of Ireland was a nobler call, in a holier cause, than any other call issued to them during this war.”

As well as outlining how the Rising came about, this chapterwill in particular attempt to explain how James Connolly came to be a dominant force in a national revolt that had little real prospect of success and whose objective – the breaking of the political link between Ireland and Britain – was significantly less than the socialist transformation of society that he stated was necessary throughout his life.

The national question and the emergence of the working class as an organised force, were the key and interconnected factors that dominated early twentieth century Ireland. The cornerstone of the national question was the oppression of the mass of people in Ireland by British Imperialism and capitalism: nationally, socially and politically. In addition people were also cruelly exploited by Irish capitalists and landlords. However, there wasalso a significant religious division among working-class people. This division between Protestant and Catholic was originally connected to the plantation policy by English governments in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and their age-old tactic of divide and rule. British Imperialism stoked up religious division among ordinary people when it suited as a ploy to split the opposition they faced, all the better to rule and exploit Ireland and the people themselves.

By the early twentieth century, the revolutionary national movement of the 1798 United Irishmen Rebellion or the more plebeian movements of Robert Emmett, and to a certain extend the Fenians, were but a distant memory. In general the Irish nationalist movement, dominated by the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) led by John Redmond, had become conservative and Catholic in character. This meant that for many in the North-East, particularly Protestants whose livelihoods were intimately connected to the economy of Britain and the industrial centres of Scotland and North-West England, there were suspicions of the nationalist movement and serious concerns about what Irish independence or Home Rule would actually mean for them. They feared that they could become economically disadvantaged and a discriminated-against minority as theIPP primarily represented the interests of the southern Catholic capitalist class.

The emergence of the Irish working-class movement (which by its nature tended to unite Protestant and Catholic workers around their common material interests as workers) onto the scene of history posed a potential solution to this division and national conundrum. As shown in previous chapter, James Connolly felt this development marked a critical change and held the view that British Imperialism could be defeated, but only if the new working-class movement, both Protestant and Catholic, led a mass struggle against capitalism and British Imperialism for socialist change. Unlike before, now a force existed that could potentially unite the mass of people under a banner for national freedom precisely because it also promised to break with capitalist exploitation and offered a real future.

For Connolly, the national struggle had become synonymous with the working-class struggle for socialist change. He viewed the fight against national oppression and for Irish independence as clearly very important and progressive, but also that it was limited. He often poured scorn on ‘patriots’ and nationalists, and just a few years before the Rising he famously dismissed any ‘independence’ that maintained capitalism as not worth fighting for.

In Workshop Talks published in 1909 he wrote, “After Ireland is free, says the patriot who won’t touch socialism, we will protect all classes, and if you won’t pay your rent you will be evicted same as now. But the evicting party, under command of the sheriff, will wear green uniforms and the Harp without the Crown, and the warrant turning you out on the roadside will be stamped with the arms of the Irish Republic. Now, isn’t that worth fighting for?”

Connolly’s approach was to adopt positions, including on the national question, based on a belief in the working class as the force for change. As Connolly often expressed his views in quite stark terms, the contrast between his views here and then his alliance with the IRB only a few years later is also quite striking. The basis of this change can be found in developments in 1914 thathad a profound effecton Connolly’s outlook.

Setbacks and growing dismay

The last of the workers involved in the great Dublin Lockout didn’t return to work until March 1914, such was their defiance. In an immediate sense the outcome of the Lockout was a cruel defeat. Those workers who could went back to work on the basis of having to leave the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU). Others were blacklisted into even worse poverty. The bosses had the whip in hand and used it to intensify exploitation.On a deeper level, however, the nature of the struggle that had been waged served to transform attitudes and establish a fighting tradition deep in the psyche of the emerging workingclass. In the years that followed this re-emerged with a vengeance and helped tip the balance in favour of the working class.

While the bosses had won this round, they were also horrified by the resistance that the working class had displayed to their attacks and starvation tacticsduring the Lockout. It wasn’t fully apparent at the time but the battle had actually loosened their tight grip on power. When circumstances allowed, starting in 1916, not only did the ITGWU recover quite dramatically, it was also clear that a deep class hatred of the bosses had taken root, along with support for militant tactics and solidarity action among workers.

Nevertheless, in 1914 the outcome felt like a cruel and bitter defeat. The working class had given so much, and could have won if only the leadership of the British Trade Union Congress had lifted its finger to organise some solidarity action. Many in the ranks were more than willing, but when the leadership of the British unions refused to support solidarity action at the TUC congress in December 1913, the dye was cast for the workers in Dublin. Connolly was deeply affected by this betrayal. The lack of broad solidarity action was solely the responsibility of the leaders of the TUC and Connolly’s bitterness towards them was completely understandable. However, it is likely that Connolly was also disappointed that the ranks didn’t prove capable of challenging and overturning the role of the union bureaucracy.

In his biography of Connolly, C. Desmond Greaves cites that in the summer of 1915 Connolly, in an ironic tone, congratulated the working class of Wales for “waking up” in regard to a successful struggle they had undertaken. However, Connolly’s words show that by then he had developed an overly negative assessment: “We fear they are crying out too late; the master class are now in possession of such impressive powers as they have not possessed for three-quarters of a century.” In another article in the Workers’ Republic in September 1915, he said that the British working class were, “the most easily fooled working class in the world.”

In such trying circumstances it can be extremely difficult to maintain a balanced understanding and perspective. Connolly was clearly fearful of what the future held and he undoubtedly went back and forth in his own mind on many issues. For instance, there are examples of articles where he displays an incredible sensitivity as to how economic conditions could force men who had fought during the Lockout to sign up tothe British Army. However, in an article from February 1916 entitled,“The Ties that Bind” Connolly wrote, “For the sake of the Separation Allowance thousands of Irish men, women and young girls have become accomplices of the British Government in this threatened crime (further denial of Irish freedom and rights) against the true men and women of Ireland.”

The actual setbacks for the working class and the TUC’s betrayal also clearly undermined Connolly’s confidence in the capability of the working class to be the decisive force for change. As the general secretary of the ITGWU, Connolly organised and fought as best as he could day in and day out to defend the rights of the working class, right up to the eve of the Rising itself, but clearly he began to question if major class battles and a struggle for socialist change was off the agenda for an historic period.

While the consequences of the Lockout’s defeat were still unfolding in 1914, the whole of Europe was gripped by a new crisis. On 28 June,the Austrian royal prince Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot and killed in Sarajevo. In just over a month, like the proverbial bolt from the blue, the world was at war. Before the First World War would finish, 70 million people would be mobilised and more than 16 million would be killed. It was the outbreak of the world war and the refusal of the international socialist movement to resist it that had the biggest effect on Connolly and led him to become very fearful of what the future held.

Outbreak of war and betrayal

The existence of webs of military alliances involving the different powers in Europe facilitated the mushrooming of tensions between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Serbia following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand into a multi-nation conflict. However, the war didn’t happen by accident or just because of the assassination of a lesser royal.

The First World War was an imperialist conflict fought in the context of increased capitalist economic competition, the saturation of markets and stagnation. In the main it was between British and emerging German Imperialism to see which one would get the “right” to dominate and further exploit the other nations of Europe and their respective colonies. The extensive military alliances and the fact that arms spending had increased in Europe by 50% since 1908 illustrate how economic and military tensions had been building for years.

With a small number of honourable exceptions, including Connolly and the Bolsheviks in Russia, the international socialist movement instead of opposingthe inter-imperialist war, shamefully supported the rulingclassesof their own nationsin the conflict and endorsed the fighting between workers from different countries in the interests of the imperialists. The anti-war resolutions of international socialist congresses in Stuttgart in 1907, Copenhagen in 1910 and Basle in 1912 all came to nothing.This betrayal by the parties of the Socialist International and the European trade union movement was as much of a body blow to Connolly as the outbreak of war itself. Connolly’s deep fears for what the world war could lead to brought him to the conclusion that he had to dedicate himself wholly to do all he could in Ireland to oppose it and British Imperialism’s war effort.

Connolly feared that the war would see the slaughter of not just the working class on an industrial scale, but also of the flower of the European socialist movement and therefore set the struggle back for many, many years. He also feared that Britain would win the war and believed that the result would be a decisive strengthening of British Imperialism and heightened exploitation by it of the markets and resources of other countries, including a further consolidation of its rule and domination of Ireland, i.e. a new reactionary phase of capitalist dominance.

The war was a serious defeat for the working-class and socialist movements. It dwarfed the defeat in the Lockout but at the same time it re-enforced the negative sentiments or perspectives that Connolly had formed as a result of it. While publicly continuing to argue for class struggle and socialist change, increasingly Connolly’s actions indicated that he believed that the prospects for the potential for a working-class movement against the war had “receded out of sight”.[i]

In a sense, Connolly was a victim of his own hopes in revolutionary syndicalism. He was knocked when there wasn’t widespread industrial action from below throughout Europe against the war, given the anti-war resolutions and manifesto’s and the substantial support in different countries for “revolutionary unionism” (syndicalism) which supported the idea “that when the bugles sounded the first note for actual war, their notes should have been taken as the tocsin for social revolution.”[ii]

Wars, along with revolutions, are the most momentous and profound events that can occur and affect every aspect of society. Pre-existing resolutions, unless backed up by a strong and living movement that acts as a leadership to the working class, were never going to be enough to withstand the drive of the different capitalist powers into war. Manufactured pretexts to justify the war, like defending the rights of small nations, the whipping up of jingoism and the support of the population for the ordinary soldiers of their own country in a conflict are real issues that would have to be countered and fought anew regardless of past resolutions.

The war showed that the parties of the Socialist International had degenerated from revolutionary internationalism to reconciliation with capitalism and its wars. Over a period of years, the main socialist parties became increasingly incorporated into the capitalist establishment and state and in practice had a reformist outlook. In reality it would have been extremely difficult to prevent a war that was materially rooted in the economic contradictions of capitalism at the time. But there wasn’t a strong enough revolutionary movement or party in any European country that was capable of successfully standing against the momentum for war and the sell-out of social democracy.

Connolly was undoubtedlyshakenby these developments andhe resolvedrelatively quickly that his hopes and perspective for social revolution against war were not going to materialise. Notwithstanding that, he felt it was imperative that the war be challenged but he also knew there was little basis for a mass revolt from the working-class movement at that time.

He was correct to be open to co-operation with the Irish Volunteers and the IRB in resisting Britain’s war effort, including organising against recruitment drives and the threat of conscription. However, so desperate was Connolly to resist the war that he was also open to having an alliance with the IRB for the purpose of an insurrection against British Imperialism’s war effort. Connolly’s preference was for a rising that had a mass working class and socialist character, but as he didn’t believe that was possible, he was prepared to look elsewhere in order to maximise the impact of a rising. As the months passed and the horrors of the war became even more apparent, his resolve for some form of rising only intensified.

War: “the mid wife of revolution”

Sadly Connolly was isolated from the other revolutionaries internationally who also stood out against the war. The Bolsheviks in Russia led by Lenin were as desperate as Connolly to strike a blow against the imperialist war but they were capable of collectively analysing developments, and their assessment led them to the view that mass opposition to the war would develop that would not only create the basis to stop the war but also produce revolutionary uprisings.

In the summer of 1915 Lenin wrote a pamphlet entitled Socialism and War. In it he outlined the following assessment of perspective and tactics:

“The war has undoubtedly created a most acute crisis and has increased the distress of the masses to an incredible degree. The reactionary character of this war, and the shameless lies told by the bourgeoisie of all countries in covering up their predatory aims with “national” ideology, are inevitably creating, on the basis of an objectively revolutionary situation, revolutionary moods among the masses. It is our duty to help the masses to become conscious of these moods, to deepen and formulate them. This task is correctly expressed only by the slogan: convert the imperialist war into civil war; and all consistently waged class struggles during the war, all seriously conducted “mass action” tactics inevitably lead to this. It is impossible to foretell whether a powerful revolutionary movement will flare up during the first or the second war of the great powers, whether during or after it; in any case, our bounden duty is systematically and undeviatingly to work precisely in this direction.”[iii]

With these powerful words Lenin embraced the negative features in the situation but put them in the more fundamental and general context of the crisis that capitalism was facing. Lenin and the Bolsheviks understood the dangers contained in the war but they also understood that the war – as it was linked to an organic crisis in capitalism internationally – was also likely to create a series of revolutionary opportunities.

There was no guarantee as to when this might happen. Lenin held out that there was a possibility that the current conflict could cease quite quickly, but only to be replaced by another one soon enough. However, what is clear is that he and the Bolsheviks understood that the war posed serious dangers for capitalism too and that it was likely that there would be movements against the war and the conditions that the war was creating in the relatively near future. Crucially Lenin insisted, that even if it wasn’t clear when such movements might occur, it was vital that revolutionaries stand their ground and stick to their principles and prepare for such mass working-class radicalisation and revolts, as that is the only way to ensure the success of the socialist revolution. This would in turn be the only way to stop capitalist wars and really transform the lives of the working class, the small farmers and the poor. As it turned out, on the basis of this perspective and careful preparation, in a little over two years the Russian working class led by the Bolshevik Party took power and that revolution and its impact globally was key to ending of the First World War itself.

It is extremely unfortunate that Connolly was isolated internationally and didn’t have direct contact with the likes of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, as perhaps their analysis and position may have had an impact on him and help correct the mistake he made in mainly seeing the dangers and not the revolutionary opportunities that the war would ultimately bring. That mistake inanalysis and perspective in turn led Connolly to put all his energies into one defiant act, the Rising.

History was to prove that the mass radicalisation and struggle that the Bolsheviks believed would happen also developed in Ireland, particularly between 1917 and 1920, something which Connolly didn’t think likely or possible. In a sense, even within Ireland Connolly was isolated in that he didn’t benefit from having a genuinely Marxist organisation or party, similar to the Bolsheviks, where the issues could be debated and clarified in order to formulate the clearest perspectives and best strategies and tactics.

The Irish Volunteers split

The Irish Volunteers were established in 1913 on the initiative of members of the IRB who saw in the rise of the Ulster Volunteer Force in 1912 a chance to launch a broad military movement in the south in response. The outbreak of the war caused a split in the Irish Volunteers in September 1914.During thatsummer John Redmond, leader of the IPP, used his position of influence to issue an ultimatum that whichever people he nominated must be incorporated onto the executive of the Irish Volunteers. Most of the members of the IRB, which was working inside the Volunteers in a clandestine fashion, opposed this but the ultimatum was acceded to by the executive of the Volunteers, which had a broader and more moderate composition. This put the IRB at a serious disadvantage and tensions rose.

The actual split came about because Redmond came out in favour of the British war effort and acted as a recruiting agent for the British Army. Of the estimated 150,000 members of the Volunteers, the vast bulk went with Redmond and became known as the National Volunteers. Just over 13,000 opposed Redmond’s policy and stayed with the Irish Volunteers, which was lead by prominent academic and moderate nationalist Eoin MacNeill. The IRB had control of many vital positions in the new Irish Volunteers.

Less than a month after the war was declared, leaders of the IRB decided in principle that there should be a rising during the war, if two conditions pertained. These were that Britain tried to impose conscription on Ireland and that German troops would be involved in a rising.

While the IRB secretly took senior and influential positions, they also allowed more moderate elements, like MacNeill, to take the public leading positions. Formally MacNeill was President of the organisation. With their secretive tactics they hoped to operate unhindered behind the scenes to connect with and influence others in the Volunteers. They hoped to be able to use their positions to get the Volunteers to participate in an armed uprising at the right time, regardless of what view MacNeill as leader adopted or what other moderates might say or do.

Connolly agitates for action

Connolly became general secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) just before Larkin left for America on 24 October 1914 – for what was to be a fundraising tour but turned out to be a visit that lasted seven years! While Connolly engaged in a reorganisation of the union and remained very involved in industrial affairs, he increasingly honed in on the need for an armed rising.

Initial connections between Connolly and members of the IRB developed in September 1914. His relations with the IRB/Volunteers over the next year and a half went through the gamut of possible relations – suspicious, supportive, critical, hostile, encouraging, contemptuous and friendly – depending on the time and what he considered to be their attitude to a rising. Resolved that there had to be a rising against the capitalist war– against British Imperialism and its war effort – and with the knowledge that the trade union and socialist movement was not a likely support base for such an initiative, Connolly consciously elevated the issues around national freedom and identity in his propaganda and agitation in order to win support for a rising.

If before Connolly had indicated that the national and labour questions where synonymous in a way which incorporated the national question into the struggle for socialism, he was now inclined to pose it the other way around. This was not because he suddenly changed his actual position – putting the achievement of national liberation above the goal of socialist change – but because he reasoned that in the circumstances, such an approach would solicit more possible recruits for a rising. He also directly targeted agitation towards the ranks of the Volunteers and the IRB against undue delaying and fora stand being made. In fact he engaged in a continuous public polemic against the inaction and conservatism of the Irish Volunteer and IRB leaders and encouraged the ranks to challenge it. This sometimes created deep hostility and consternation among the leaders of the Volunteers and IRB. Connolly also went about convincing the Irish Citizens Army and some others in the unions of the need to make an alliance with the more militant sections of nationalism in order to prepare a rising.

The Irish Volunteers held a congress on 25 October 1914. At least on the surface it seemed from this conference that they adopted a more hesitant and cautious approach from what leaders of the IRB had initially indicated. The secrecy under which the IRB operated meant it was difficult to be clear of exactly where they stood, as opposed to the Volunteers and MacNeill. Tensions between Connolly and the nationalist movement intensified as he was impatient but also because he feared they may be pulling back from the idea of a rising at all.

State repression in December intensified and this hit the publication of both socialist and nationalist newspapers. The Irish Neutrality League, a new public propaganda banner in which the IRB, Connolly and some others in the unions co-operated together, wasn’t able to function under the repression and it lapsed. As 1915 dawned and then as it wore on, to Connolly it didn’t seem as if the IRB/Volunteers were making serious preparations for a rising. In fact a Military Council had been established in May to look into and plan a possible rising.

When the old Fenian, Jerimiah O’Donovan Rossa, died in New York at the end of June 1915, Tom Clarke (who was an essential organiser of the Rising in the IRB) insisted that his body be sent back to Ireland as he saw that this could be used help ferment support for an action. Connolly and the ICA co-operated in the preparations for the funeral and in the parade and celebrations on day itself. At the same time Connolly used the occasion to try to maximise the pressure on all the leaders of the IRB/Volunteers. He remained suspicious of the intentions of the IRB in part because they continued to allow Eoin MacNeill, who didn’t support a rising, to remain unchallenged as the Volunteer’s leader.

On 31 July Connolly wrote in the Workers’ Republic:

“O’Donovan Rossa represents to us a revolutionary movement the least aristocratic and the most plebeian that ever raised itself to national dignity in Ireland…magnificent must have been the courage, splendid the idealism of the men and women who with the awful horror of the famine of Black ’47, and inglorious ’48, still in their minds were yet capable of rising to the spiritual level of challenging the power of England in 1865 or 1867. They were giants in those days! Are we pigmies in these?”

At another time commenting on the Volunteers leaders, Connolly likened them to people who, “all their lives sung the glories of the revolution, when it rose up before them they ran away appalled.”

The ICA and Volunteers

Later in 1915 and reflecting his concerns and impatience, Connolly made it known that he was prepared to lead the ICA out on its own if the Volunteers continued to dither. Clearly this was in part designed to maximise the pressure on the Volunteers and IRB, but it couldn’t have been considered to be an idle threat either, given Connolly’s desperation. In the Workers’ Republic of 30 October 1915 he wrote:

“The Irish Citizens Army will only co-operate in a forward movement. The moment that forward movement ceases it reserves to itself the right to set out of the alignment, and advance by itself if needs be, in an effort to plant the banner of freedom one reach further towards its goal.”

Connolly had called on all those who were not willing to be active and to drill to step back from the ICA in order to allow those who were prepared to be active to step forward. Then in late 1915 it is reported that Connolly discussed individually with each member of the ICA as to whether they were prepared to engage in an armed rising as just the ICA, without the Irish Volunteers. That he received universally positive responses illustrates that his propaganda and agitation had been successful, but also spoke of the force of his personality and his authority within the ICA.

Some of the key leaders in the IRB wanted and were pushing for a rising too. However, as far as Connolly was concerned, there was hesitationand a lack of sureness and seriousness. He exerted huge pressure on the IRB over an extended period of time and on 16 January 1916 the Supreme Council of the IRB made the decision to hold a rising on a specific date in the coming months, regardless of whether their previously stated conditions existed or not. Three days later, on 19 January 1916, they urgently requested an immediate and secret meeting with Connolly. No one in the ITGWU or from Connolly’s family knew where he was; he had simply disappeared. That was the start of the famous three-day of discussions where the plans for a rising were outlined and discussed with Connolly. He re-emerged late on Saturday evening having come to agreement with the IRB. A rising would be held on 23 April, i.e. Easter Sunday 1916.

Regarding his three days of unscheduled absence, Connolly said little. He did however comment that it represented a “terrible mental struggle” for him. It wouldn’t really make sense that Connolly would have struggled over the idea of joint action with the Volunteers, as that is what he had been trying to goad them into for over a year. It is more likely that before he agreed to the plan and the date that he reflected on whether he could wait another three months, but perhaps particularly on whether he could trust the IRB/Volunteers to actually follow through or would they delay or get cold feet and put it off.

He is likely to also have reflected on how many of the 13,000 members of the Volunteers would the IRB actually deliver. Connolly was open about his desire for a rising, he agitated and recruited for it quite openly. The IRB took the opposite approach. They kept their plans secret from the Volunteers. Pearse, as Director of the Military Organisation would issue orders for parading and manoeuvres to take place over the Easter holiday weekend. Then, when whatever number of the Volunteers turned out on the evening of Easter Sunday, they would be informed that it wasn’t a parade or a drill but was in fact an actual rising.

This approach meant that considerable uncertainty would exist right up until the last minute as to the numbers that may be involved, which in turn could materially affect exactly how the rising might go – how long it could withstand the British military. While the IRB had dropped the conditions they had felt necessary for a rising,on their behalf Roger Casement was in negotiations with the German state in order to get some support. A shipment of arms and ammunition was agreed and scheduled to arrive off the west coast just before the time of the rising.

What Connolly really stood for

In 1916 Connolly continued to put forward a class and socialist viewpoint, but this was increasingly interspersed with appeals for people to rise up that were centred on the need for Irish freedom alone, even more than a year previously. Often the same articles or speeches contained contradictory points or comments, for example stating the importance of the independence of the working-class movement while quickly advocating an alliance with nationalism. There is no doubt that Connolly and his anti-capitalist and socialist argumentation had a considerable impact on a number of the leaders and members of the IRB, pushing them some way towards the left. Others in the IRB, including some of the key leaders of the Rising, remained economically and socially conservative.

Over an extended period Connolly made statements and arguments that served to imply that Irish nationalism or an Ireland, free from Britain’s political control, would be innately pro-working class. This was in stark contrast to the general position he put forward over many years in which he showed the serious limitations of nationalism. In an article entitled “Economic Conscription” in the Workers’ Republic just before Christmas 1915 he stated:

“We cannot conceive of a free Ireland with a subject working class; we cannot conceive of a subject Ireland with a free working class. But we can conceive of a free Ireland with a working class guaranteed the power of freely and peacefully working out its own salvation.” Later in the same article he wrote, “nationalists realise that the real progress of the nation towards freedom must be measured by the progress of its most subject class.”

The reason Connolly put forward such argumentation has been explained earlier, but it is still a mistaken approach. Instead of raising people’s consciousness about what needs to be done to actually achieve real change, such an approach can cause confusion and create illusions in forces that don’t represent the working class, and who can quickly turn and begin attacking the interests of working-class people. Previous to this, Connolly would oppose and fight national oppression but would also criticise “patriots” and nationalists. He did this because he thought Home Rule or an independent state was likely at some point and so these criticisms were a warning to the working class that the struggle must continue.

In contrast, in the period before the Rising he was trying to agitate on issues of nationality and was willing to bend the stick because he felt that that was the best way to increase the numbers involved in a rising, given that class struggle and the working class movement was at such a low ebb. That Connolly, in reality, did not believe an independent state was a possible outcome from the coming rising,also probably meant that he felt freer to forgo warnings about the dangers of nationalism. C. Desmond Greaves reports that a week before the Rising, after a lecture on street fighting and in the context of informing the members of the ICA of the Rising, Connolly said:

“The odds are a thousand to one against us. If we win, we’ll be great heroes, but if we lose we’ll be the greatest scoundrels the country has ever produced. In the event of victory, hold on to your rifles, as those with whom we are fighting may stop before our goal is reached. We are out for economic as well as political liberty.”

This comment (and the factthat Connolly ensured that the Starry Plough flag of socialism flew over William Martin Murphy’s Imperial Hotel during the Rising itself) shows that he maintained his basic position, but tellingly this statement was not made publically, just to the ICA. However, some in the ICA and the ITGWU had issues with the evolution of Connolly’s political position, his alliance with the IRB and his willingness to participate in a rising on the basis that he did. In Emmet O’Connor’sBig Jim Larkinbiography, it is reportedthat in late 1915 from America, aware of the possibility of a rising, Larkin sent a message to Connolly “not to move”. Activist and playwright, Sean O’Casey, also resigned from the ICA because he was opposed to the connection with the IRB, the Volunteers and nationalism.

In April 1916, the plan to raise the green flag over Liberty Hall in the weeks before the Rising wasn’t initially accepted in the ITGWU. It was opposed strongly at a meeting thatresulted in a second meeting. There the opposition continued even though Connolly indicated that he would resign as general secretary of the union if agreement couldn’t be reached. Ultimately a break was called in the meeting thatallowed for some private discussion and this resulted in the objection being withdrawn.

It is one thing to recognise that a stand against British Imperialism and for Irish freedom was progressive and a step forward. It is another thing to put your name to a document that, in the case of The Proclamation, you know is likely to become an important and historic document but which has no class or socialist analysis or content.

Some see The Proclamation as an aspirational document but it is all depends on your interpretation and where you are coming from. Ordinary people may see it as a promise of democratic rights and equality. It implies there is no class division or different class interests when it calls for the “establishment of a permanent National Government, representative of the whole people of Ireland.”But while it aspires to the “common good”, there is nothing in it that would have challenged the existing model of private ownership of wealth. Given that private ownership inevitably leads to gross inequality, the people who would benefit most from the vagueness in The Proclamation would be the already existing rich and powerful, who Connolly had previously criticised mercilessly.

Although Connolly had a lifetime of socialist activity behind him, including often publicly stated socialist aims and objectives, this did not suffice in explaining to the wider working class his role and that of the ICA going into and during the Rising . It was a significant mistake that Connolly and the ICA did not produce and then disseminate their own public statement and programme during the Rising on the independent interests and goals of the working class and the need for socialist change. This lack of clarity and confusion has allowed all sorts of political forces that are in reality opposed to Connolly’s socialism to claim his mantle and distort his role.

Plans for the Rising go awry

Inorder to manoeuvre Volunteer President and Chief of Staff Eoin MacNeill to go along with the rising when it was to be publically declared, a Sinn Féin member of Dublin Corporation read out a document at a meeting on Monday 17 April that he said had come from Dublin Castle. This document said that the British Administration in Dublin was about to launch a major crackdown against the Volunteers, including arrests. This document, which some commentators say was likely the work of Military Council member Joseph Plunkett, may actually have raised the suspicions of MacNeill and other moderates, like Bulmer Hobson, who was actually a leading member of the IRB but didn’t agree with the idea of a rising.

Clearly they had a sense that something was afoot and on Tuesday 18 April, five days before the Rising, MacNeill and Hobson confronted Patrick Pearse at his home as to whether a rising was about to take place. In the course of the exchanges Pearse confirmed their fears.MacNeill then issued a countermanding order, cancelling all parades and manoeuvres for the coming Easter weekend that Pearse had already called. IRB leaders discussed with MacNeill and appealed to him, on the basis that a rising was going to go ahead in any case, not to act in a way that diminished it. He agreed to withdraw his countermand and so it seemed the plan was back in place.

However, when the word came through that the boat, The Aud, with the German arms shipment, had been scuttled by its captain as it was about to be apprehended by the Royal Navy, MacNeill changed his position again. On the night before the Rising was due to take place he sent orders around the country cancelling all mobilisations for the weekend. He also took out ads in Sunday papers to the same affect.

Amid this chaos, the Military Council whohad planned the Rising met in Liberty Hall on Sunday morning. They made the decision that the Rising would still go ahead. Instead of the original plan of 6.30pm on Sunday evening, it would now begin at noon on Monday 24 April, less than a day’s delay. They attempted to get word out as widelyas possible, but in the circumstances, mixed messages and confusion were inevitable.

It was fortunate that they didn’t delay any longer. If they had they would undoubtedly have been arrested as at the same time as the Rising started, word came toDublin Castle from London authorising their request to move against the rebels as the British state had information that a rising was imminent. If the Military Council had delayed even a few hours, their plans are likely to have been completely cut across.

William O’Brien witnessed the final preparations at Liberty Hall just before the Rising on Easter Monday morning:

“When I arrived there about 10am all was bustle and excitement. Large numbers of Volunteers and Citizen Army men were continually passing in and out. Quantities of ammunition and bombs were been taken out of the premises and loaded into cars and trucks…I went downstairs to get my bicycle. I found difficulty in getting it out owing to the large number passing out through the front door. While I waited an opportunity Connolly passed down the stairs and shook hands without speaking. As I cycled across Abbey Street I saw the Irish Republican troops breaking the windows of “Kelly’s for Bikes,” and dragging bicycles and motor-cycles across the street to form a barricade…The fight was on.”

Notes

[i] “Revolutionary Unionism and War (1915)”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1915/03/revunion.htm

[ii] Ibid

[iii]Socialism and War:The Attitude of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party Towards the War

https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1915/s+w/ch01.htm#v21fl70h-299