The following article was first published in Socialism 2000, the precursor of Socialist Alternative, in the immediate aftermath of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement that was signed 20 years ago today.

By Peter Hadden

Around the world the Good Friday Agreement may have been trumpeted as an “historic compromise”, an “exercise in reconciliation” and a “step to a final solution” to decades of conflict.

Within Northern Ireland, and especially within the working class communities, there has been no such view. Most people were relieved that there was agreement rather than disagreement but the mood was sceptical from the start and is increasingly so.

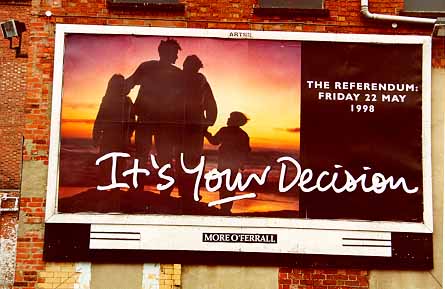

The Socialist Party’s view on the referendum and the deal is in line with the approach of most working class people. We do not endorse this deal which is neither a solution, nor the basis of a solution, but we think it is preferable to vote Yes in order to continue with the peace process and in order to defeat the reactionary and backward looking forces who make up the No camp. Asked to choose between two roads to sectarian conflict we choose the longer, if only because it gives the working class movement more time to mount a challenge to the sectarians. Our position is clear and distinct. The various ultra-left groups on the other hand have taken a different stand. All have come out for a No vote. The deal, they argue “has been brokered by imperialism”, “does not smash the state” or “disband the RUC”, therefore it should be opposed. This simplistic view that where the ruling class puts a plus the working class automatically must put a minus leaves these groups all at sea in the very complex Northern Ireland situation.

The real yardstick for socialists when considering the national question is what effect a particular stance will have in raising or lowering class awareness or consciousness as opposed to national consciousness and whether it will strengthen or weaken the working class movement.

In our view a No victory would be a victory for right wing sectarians, Orange and Green, would lower class consciousness and would quite drastically weaken the potential for unity between Catholic and Protestant workers.

The ultra-left shrug their shoulders as though this were of some passing significance. The largest of these groups, the Socialist Workers Party, has this to say: “The alternative is not civil war or armed conflict … In the unlikely event of the settlement being rejected that same pressure for peace would continue and socialists would give it every support.”

This unreal scenario is then the basis for the following conclusion: “It is time to break from all the sectarian agendas and put class politics to the fore. Voting No to this deal will mark a start.”

It is fortunate for all of us that the working class have enough sense to understand that the last thing a No vote would result in would be the coming to the fore of class politics and will be deaf to such “advice”. It would be a victory for the camp of Paisley, McCartney, the LVF – and no-one else. There would be no Agreement, no Assembly elections and the idea of sending the political parties back to the table would have no credibility. In short the peace process would be in tatters.

Would the working class then step onto the scene to offer another way out? Of course we cannot entirely dismiss this as a theoretical possibility but it would be extremely unlikely. The working class movement would be stunned and demoralised by the No victory. The present right wing leadership would most likely signal a retreat. The socialist left is not powerful enough at this moment to offer an alternative. Much more likely it would be the most confrontational sectarian forces which would step into the political vacuum left by the collapse of the Agreement.

The effect of a No vote on the consciousness of the Catholic population would be immediate, dramatic and enduring. It would be seen that Protestants had said no to even a minimal equality agenda. This time it would not be just the unionist politicians who would be held responsible, it would be the broad mass of the Protestant population.

As when the demand for civil rights was blocked by unionists in the late 1960s, Catholics would conclude that there is no possibility of respite within the Northern state. Nationalism, of the most virulent and sectarian variety, would be reinforced. Far from putting “class politics to the fore” it would mean that among Catholics, North and South, the idea of building class unity with Protestants would seem less than credible. Those, like the Socialist Party, who would continue to advocate this would risk isolation.

Within weeks of the referendum result there would be the fourth confrontation over Drumcree. With Catholic indignation over the Protestant No on the one side, and the victorious unionist hard-liners on the other, it is difficult to envisage how there could be a peaceful outcome. Rather there would be the potential for widespread sectarian violence, for pogroms, even for a descent towards civil war to begin. This is why the Socialist Party rejects the light-minded arguments of the ultra-left and stands for the defeat of the right wing No camp in the referendum.

Origins of the Agreement

The current juncture, and with it this deal, has been arrived at through stalemate, war weariness and not through reconciliation. When the IRA campaign began in the early 1970s we argued that this method of struggle would not succeed, that its net effect would be to divide the working class, the real agency for progressive change in society.

When the Republican movement developed the armalite/ballot box strategy in the early 80s we argued that these two methods of struggle were mutually exclusive. While circumstances might allow the secretive methods of individual terrorism to run alongside the public mass electoral work for a period, ultimately they were bound to lead in opposite directions.

Sinn Fein’s peace strategy was born out of the exhaustion of the military tactic and the realisation of this by a decisive section of the northern leadership. The electoral successes remained partial and the twin objectives of overtaking the SDLP and of making a breakthrough in the South remained out of reach. On-going military activity came to be seen by the leadership as a barrier to these goals.

Meanwhile the theoretical basis of republicanism received a shock with the signing of the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement. The real truth is that, from as early as the 1960s, the British ruling class would have preferred to withdraw from Northern Ireland. Partition had outlived its historic usefulness and they would have preferred a single independent capitalist state in Ireland which they would have striven to dominate by economic, rather than by military or political means.

The fact that the million strong Protestant community would not accept this, and that withdrawal would have led to civil war – with huge repercussions in Britain and internationally – made them hold their hand. When the IRA campaign began in earnest in the early 70s, their stated target was the British military presence, and the objective was to force withdrawal. In fact the campaign was based on a false premise: – that the British stayed out of an on-going imperialist interest rather than because the threat of civil war gave them no choice.

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was drawn up as a part of the then British strategy of concessions to win over the Catholic middle class and isolate Sinn Fein and the IRA. Its main agenda was a security one – to leave the republican movement without the cover of broad popular support and therefore easier dealt with by military means. That Agreement – which it should be remembered was also proclaimed to be an historic breakthrough – failed in this.

But it caused the republican leadership to question whether their basic premise – that Britain retained an imperialist interest in maintaining partition – was correct.

Signals from the republican leadership that there might be a way forward through dialogue were picked up by British intelligence. By the end of the decade the ruling class were embarking on a new strategy. Instead of attempting “solutions” which would isolate and undermine the “violent extremes” the new objective became an “all embracing process” which could bring all but the most recalcitrant of the republicans and loyalists in from the cold.

The statement by Secretary of State Peter Brooke that Britain had no “selfish, strategic or economic interest” in Ireland was at one and the same time a signal to the republican leadership that the door of negotiation was open and a hook to entrap them on a peace strategy from which they would not be able to turn back.

These processes were reinforced by the collapse of Stalinism, the apparent supremacy of the market and apparent demise of socialism, the strengthening of the position of US imperialism as the “one world power” with an increased ability to intervene and exert leverage in conflict situations. As with the ANC and PLO, the republican movement was thrown off-course by these developments and began to shift to the right. So this “anti-imperialist” movement ended by leaning on the representatives of US imperialism and looking to agencies of world capitalism such as the UN to help find a way forward.

The 1994 IRA cease-fire was the product of all this. Most fundamentally it came about because the theoretical basis of the IRA campaign was eroded and when the campaign itself reached a point of exhaustion.

By this stage the war weariness felt by the mass of the population had turned into open opposition to what had come to be seen as vicious and pointless military attacks carried out by both loyalist paramilitaries and by republicans. The working class began to take to the streets demanding a halt to all killings.

This had an effect on the UDA and the UVF, just as it had on the IRA. It strengthened the case for a loyalist cease-fire which was being put forward by some of the 70s generation of loyalist prisoners who were emerging from the prisons with a more sophisticated view. Sensitive to the growing revulsion at loyalist atrocities and also aware that the IRA campaign had been effectively contained, they were able to gain support for the view that loyalist violence should end.

By any reckoning the years since the cease-fires have seen the division within society, especially the division between working class people, deepen quite dramatically. During this time the events which have had the most dramatic impact have not taken place in the Castle Buildings talks complex. They have occurred in the few acres of land in and around the Drumcree churchyard and along the Garvaghy Road. The fall-out from these confrontations and from the manner in which the route was cleared for the Orange marchers has vastly increased the sectarian polarisation.

Paradoxically the very fact of the cease-fires and the talks has also added to the division. By the end of the 80s the Troubles had ground into a stalemate out of which a certain stability had been created. The violence had reached the “acceptable level” which, during the explosive events of the early 70s, the ruling class could only faintly hope would one day arrive. The “peace process” disturbed this relative equilibrium. The prospect of talks in which all issues would be on the agenda created new uncertainties.

These were added to by the efforts of the main parties to marshal their respective communities behind their narrow sectarian agenda on every issue that came up through the negotiations. Even the Yes campaign in the referendum has been a further exercise in polarisation – one side rousing Protestants to vote Yes for the union, the other urging Catholics to vote Yes to help bring a United Ireland closer.

When the parties emerged in self-congratulatory mood from Castle Buildings on Good Friday the unpleasant truth was that their efforts had moved the two communities further apart. And when the votes in the referendum are counted, the real truth, obscured by the euphoric cacophony of the world’s press, will be that the net result of the victorious Yes campaign will have been to widen the sectarian divide even further.

A real solution can only be based on unity of working people and the integration of the communities. It means not just a coming together on social issues but a coming together also on the difficult and currently divisive issues which arise from the national conflict. An agreement which has widened all these divisions and which sees no way of overcoming them is no solution.

An undemocratic and sectarian fudge

Long before the parties reached agreement on anything, those on board the NIO propaganda machine were busily preparing to greet the talks outcome as an “historic opportunity”, a “chance for peace which would not come again for a generation”, and so on. Since Good Friday the churches, business organisations, the trade unions and others have risen on cue from the NIO and repeated the idea of a new beginning, a chance for peace and prosperity etc.

Examined more soberly what is remarkable about this slender product of two years negotiation at a cost of £10 million, is not how much, but how little, has been agreed. The final text was thrown together in “indecent haste” under pressure from the London, Dublin and US administrations. Their primary concern was to come out with something and get it up and running before July, Drumcree IV, and the possibility of the whole process being shattered. During the final marathon sessions at Stormont it was a case of agree what could be agreed and brush everything else to the side. With the talks structure running out of time the participants basically agreed to the setting up of new political structures within which they can carry on the conflict – and to very little else.

What resulted is a fudge on most issues, albeit a cleverly concocted fudge which allows different sides to read what they want to read into it. The Agreement is not some new vision, creating new sets of relationships to take society beyond the conflict. It does just the opposite. It takes the existence of the sectarian divide as permanent and, rather than diminish it, effectively casts it in concrete.

Assembly members must declare themselves either unionist, nationalist or “other”. That unionists and nationalists each have a veto on key issues indicates the underlying assumption that the “other” category will always be an irrelevance. In other words it reflects the view that there can be no solution, no reconciliation, but that sectarian politics will forever dominate.

Those who constructed the deal might counter that the system of enforced power sharing overcomes this and forces everyone to work together. This was the premise in Cyprus and the Lebanon where power sharing was adopted as the means to balance the interests of different national and religious communities. The effect was to institutionalise the divisions and hinder the development of class unity from below. In both cases the end result was civil war and effective re-partition. If it gets off the ground, the institutionalised sectarianism of this Agreement would ultimately have no better result.

As to the debate over North/South bodies, the proposals of the SDLP and Sinn Fein would actually disenfranchise rather than empower the Catholic working class and Protestant workers also. They called for North/South bodies to be “fire-walled” from control either by the Assembly or the Dail. Unable to achieve reunification they were reduced to arguing for tokens, paltry symbols which could be presented to Catholics as the “all Ireland dimension”.

To have institutions “firewalled” from democratic control means handing executive authority over to a tiny cabal of senior government ministers, unionist and nationalist, to do what they like with the services under their control. For working people the existing parliaments, the new Assembly included, are sufficiently distant and unaccountable, without adding a further, even more remote tier, “fire-walled” from the day to day demands, needs and pressures of the working class.

Political realignments

A split is now taking place in Trimble’s UUP. Some of the six Westminster MPs who have spoken out against the Agreement are likely to either defect or be removed. Some may immediately join the DUP while others will join an anti-Agreement electoral alliance, linking with Paisley and McCartney.

The emergence of the Ulster Democratic Party, and more particularly the Progressive Unionist Party, is a direct challenge to the DUP in Protestant working class areas, especially in Belfast. The PUP are a long way from achieving the degree of political hegemony which Sinn Fein have attained in Catholic working class areas. Nonetheless they have made significant advances and will probably consolidate these by winning seats in the Assembly.

Generally the evolution of the PUP has been in a positive direction, away from the blatant sectarianism of its UVF roots. The new realignment taking shape around Paisley represents a shift in the opposite direction. As is demonstrated by its past involvement with Ulster Resistance and with the loyalist paramilitaries, the DUP has never been a conventional bourgeois party. Today it operates as the political centre of a new right wing loyalist formation loosely made up of groups like the Spirit of Drumcree, the misnamed Ulster Civil Rights Group and, most sinister of all, the LVF.

Its social composition – more politically backward rural Protestants, sections of the evangelical petty bourgeoisie and of the lumpen proletariat – plus its more consciously anti-socialist ideology, give it some of the features of fascism. It would be premature to label this a fascist formation at this moment. However, in the context of the successes of the far right in Germany, France and elsewhere, it is possible this grouping or some of its components could gravitate more consciously in this direction.

Overall an extremely bitter differentiation is taking place within unionism. This will give rise to extreme sectarianism – as is already manifest through the LVF as well as to more positive developments such as the growth of the PUP. It is extremely unlikely that these bitter differences and divisions will be resolved peacefully

The greatest shift of position in the talks and through the peace process generally has been by Sinn Fein, not the Unionists. David Trimble is far more correct than Gerry Adams in his description of the Agreement as a unionist document. Put together its proposals are a much larger and more difficult pill for the Sinn Fein leadership to swallow.

The main concessions made to Sinn Fein are on the “equality” agenda. These are not changes wrung from a reluctant British government in negotiations. Since the early days of direct rule it has been the policy of successive British administrations to eradicate the excesses of half a century of Unionist misrule. With or without the talks they would have preceded with an “equality” agenda of sorts. That past reforms of the old Orange State have had little impact on Catholic working class areas is largely down to the fact that any easing of discrimination has been accompanied by a dramatic increase in state repression, most of it directed at these areas.

As with the moves made on “equality”, so the proposals made on “demilitarisation” amount to little more than a restatement of existing government policy. There will be moves to close down military installations, reduce the army’s role, and review emergency legislation, but this return to what it calls “normal security arrangements” will be carried out “consistent with the level of threat”.

There is nothing new in the promise that if the IRA go away the overt military presence will be cut back. Whether security is lessened significantly; especially in border areas, will depend on whether the Agreement sticks and, if it does, on the effectiveness of the on-going military campaign by IRA dissidents. Only on the prisoners issue has a firmer commitment been made. Even this, the guarantee that all prisoners will be out within two years – is hedged with qualifications. Releases, it states, will go ahead “if circumstances allow”. From the government’s point of view the linking of releases to the ceasefires turns the prisoners into hostages and arm-locks the IRA and loyalist groups into a continuation of the peace strategy. It also puts substantial pressure on the INLA to declare a cease-fire, if only to prevent their prisoners opting for early release and defecting to rival organisations.

On the issue which Sinn Fein had made central – the independence of North/South bodies the Agreement awards game, set and match to the unionists. The proposed cross border structures are clearly made answerable to the Assembly and Dail. Within them there will be a unionist as well as a nationalist veto. In any case they will administer only minor functions, most of which are already areas of co-operation between the relevant public bodies, North and South.

The rest of the Agreement – the repeal of Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution, the proposed Assembly, the British-Irish Council – is unionist territory. In swallowing all this Sinn Fein have moved a huge distance, abandoning one central tenet of republicanism after another in the process. In the sense that this represents an awareness that the old methods of struggle were counterproductive, and that the old republican ideology had no answer to the problem of a million Protestants, this could be a positive development – but not if the alternative strategy of the republican leadership leads only to another sectarian dead-end albeit by a different route.

Even before Sinn Fein entered the talks we predicted that the course they were taking would ultimately lead to a split. A section of republican activists were bound to stand against Sinn Fein’s acceptance of the Agreement, against the Sinn Fein leadership entering a “partitionist” Assembly and against those who had led the “war” to destroy the state knocking on the door of ministerial office within it. Those who have broken, or are in the process of breaking away, will attempt to continue with a military campaign. The most vociferous opposition has come from republicans in the South. The great bulk of the movement in the North is likely to be swung by the mood in the Catholic areas and go along with the leadership. Many will do so without conviction, hesitant about the deal, but even more hesitant about the alternative. If a strong and united movement did not achieve its objectives in nearly thirty years of military struggle, what chance has a splinter group, especially when its on-going activities meet with hostility, even resistance, in the working class republican strongholds?

An isolated military campaign?

If the Agreement holds the new military campaign is likely to remain relatively isolated and low key. If it is conducted from bases across the border and not from republican heart-lands like West and North Belfast, it could end up resembling the “border campaign” of the 1950s. This depends on the scale of the defections and on events which could reshape the mood in Catholic working class areas.

The contradiction between political and military methods is not the only, or even the main, contradiction within Sinn Fein. Sinn Fein is a nationalist movement which has emerged from a generation of struggle, not a constitutional bourgeois party. In essence they are the political expression of the alienation of the Catholic population, especially of the Catholic working class.

During the peace process this alienation has deepened, especially through the confrontations over parades. A new and more strident nationalist mood has tended to develop in Catholic areas, helped along by Sinn Fein. Their role has been to try to marshal the Catholic working class behind their agenda, to maintain the separation of Catholic areas from the state and its institutions and to reinforce their effective control over these areas. As we have previously explained, the peace process at bottom has been about maintaining the maximum sectarian control over working class areas and about aborting the tendencies to integration which have arisen.

The peace deal is being sold by the Sinn Fein leadership as a continuation of this strategy. According to Gerry Adams it is a mere staging post, marking the end of one phase of struggle and the beginning of another. It “weakens the union” and “shortens the road to British withdrawal”. Put in these terms the new phase amounts to a continuation of the nationalist offensive by other means. Adams has hinted strongly of an electoral pact with the SDLP, the first purpose being to take the Unionist held Westminster seats in West Tyrone, Fermanagh/South Tyrone, and possibly even North Belfast – the ultimate aim being to overtake the SDLP, possibly forcing a merger at a later date.

Underpinning this strategy is the assumption that on-going demographic changes will soon leave the Protestants as a minority in the North. In this context the electoral gains and the territorial growth of “nationalist areas” are all part of the process of constantly pushing back the frontiers of unionism.

It is in these hard-line terms that republicans are being convinced to accept the Agreement. But, to borrow one of the stock of clichés used with such uniformity by Sinn Fein spokespersons, there is another and opposite “dynamic” within this deal. For the Irish and US establishment, the other components of the pan-nationalist alliance, and for the British government, the real purpose is to create new institutions within Northern Ireland to which Catholics can give allegiance and to leave the question of the border to another day. In brief it is to create a degree of stability by ending the alienation of Catholics from the state.

The aim is also to draw Sinn Fein further along the constitutional road, to suck in the leadership, and transform the party into a “tame” bourgeois nationalist party which may pay lip-service to the doctrine of struggle but has really abandoned it somewhere along the way. Just as the armalite/ballot box strategy was a contradiction in terms so the present course of the Sinn Fein leadership is pointing down two opposite roads.

It will prove impossible to participate indefinitely in the new state institutions and at the same time ensure that the Catholic population withhold their allegiance from them. For example, should some agreement ever be arrived at on policing it will be for a revamped version of the RUC either under British control or else, although less likely, under the control of the Assembly. Were Sinn Fein to argue that such a force be accepted into Catholic areas they would in effect be pronouncing the alienation of the Catholic community from the state to be at an end. On the other hand a Sinn Fein campaign to block this force on the ground would likely make their efforts to participate in an Executive untenable. On this or some such issue or accumulation of issues Sinn Fein will find that it is not possible to become part of the state and to reinforce Catholic alienation from it at the same time.

How this contradiction resolves itself will be determined by events. Mass sectarian upheaval could force the Sinn Fein leadership away from the constitutional path. A split on this issue could develop. Or, if a degree of temporary stability is arrived at, the issue could be resolved through the disillusionment and dropping away of Sinn Fein activists.

Whatever happens the present division between “doves” and “military hawks” should not obscure the latent but more fundamental contradiction within Sinn Fein between the tendency to become Armani-dressed statesmen and the strident nationalists who oppose integration of the communities and seek change through confrontation on the streets. This is not the left/right division some ultra-left groups believe will now occur. Those who complain about sell-out are likely to do so from a confrontational sectarian standpoint. In the future a more radical wing may develop – especially if the leadership accepts ministerial posts and implements pro-capitalist policies. The emergence of a class movement offering an alternative pole of attraction would help a left-wing to crystallise within Sinn Fein.

Will the Agreement stick?

May 22nd is only the first hurdle the Good Friday Agreement has to cross. The June election will in reality be a second referendum. All eyes will be on the battle between the anti-Agreement unionists and those who back Trimble. Should the former manage to win a majority of votes or seats the Agreement would be mortally wounded. Even a sizeable minority of votes and seats going to the Paisley led opposition would make it very difficult for Trimble to stay on course.

Hard on the heels of the Assembly election will come the potentially more difficult hurdle of Drumcree. Paisley and his followers in the Orange Order will surely try to make this a last stand against the Agreement. Catholics will look to what happens on the Garvaghy Road as the first real test of whether or not there is an “equality agenda”.

If the Deal survives all this it will still face the problem of establishing a new Executive Committee. Under the D’Hondt voting system for ministerial appointments it is likely, on present party strengths and assuming the DUP will refuse to accept their posts, that there would be a non unionist majority from the outset.

The issue of decommissioning could possibly raise its head and avert this problem by replacing it with another. The IRA have categorically stated that they will not decommission and it is unlikely that this could be reversed without provoking a major split. In turn the UDA and UVF will not hand over their weapons. This means that all these parties will likely be excluded from ministerial posts, saving Trimble the embarrassment of presiding over a government made up of more SDLP, Sinn Fein and Alliance members than Unionists.

Should this turn out to be the case, the new government composition of pro-Agreement Unionists, SDLP and Alliance would not look very much different from the failed 1974 Sunningdale set-up. It would face opposition from anti Agreement Unionists who would try to bring it down. Meanwhile Sinn Fein would be campaigning in Catholic areas against their “exclusion”, thereby reinforcing the sense of alienation felt by the Catholic population.

Having invested so much in the peace process, and having no real alternative at this stage, the British government will strive might and main to find a way through such difficulties. The general desire for peace, and the fear of the consequence of failure, which is still deeply imbedded in both communities, may allow the thing to splutter on. There could even be a certain breathing space with the violence at “containable” levels and with the political structures holding, however uneasily, at the top.

However this could not last indefinitely. A firm social base for the Agreement could only be created if it was underpinned by tangible social and economic benefit. A certain amount of money will likely be put in by the British government, by the European Union and the US. Apart from the capital funding of one-off schemes the money put in is unlikely to be much greater than existing levels of funding. This does little more than maintain an army of professional “community workers”, not create real jobs.

There are signs that the economy is about to go into recession if it has not already done so. This, together with the attacks on working conditions, the growth of contract and Agency jobs with lower pay and less rights, the replacement of high paid security and manufacturing with low paid service jobs, means that there is unlikely to be any substantial sense of a peace dividend.

The only basis on which the Agreement can survive is if a significant section of the Catholic working class come to accept the status quo “for the time being” and are prepared to relegate the desire for a united Ireland to an aspiration to be fulfilled at some future time. The fact that those living in the most impoverished working class areas are unlikely to sense any significant improvement in their lot limits the degree to which this will happen.

Even if the Agreement limps through the immediate hurdles the notion that there will be a stable administration made up of Trimble, Hume and Adams, or other individuals representing similar views, is quite farfetched. All the issues unresolved or only part resolved in the talks will raise their heads at some point, as will other issues, to destabilise the new Executive. The report of the Commission on policing, due in the summer of 1999, is just one of many bombshells waiting to explode onto the floor of the Assembly; should it last that long.

As time passes the authority of the New Labour government, and with it its capacity to provide outside momentum to the Deal, will decline. A New Labour administration, increasingly unpopular in working class areas, will have less capacity to place itself in the role of “honest broker” or to appeal directly over the heads of local politicians.

If the new administrative structures are put in place and hold, some degree of violence will continue, carried out by dissident republicans and loyalists. Even if the State, helped by public anger at on-going attacks, manages to partially contain these groups, the day to day sectarian violence, the intimidation etc. will continue.

So long as the sectarian parties continue to dominate, and so long as politics is carried on in terms of unionism versus nationalism, working people will remain politically polarised and the divisions on the ground will remain.

Ultimately these divisions will force through to the political surface and undermine this deal. This could happen in the short term or it might take some period of time. It could be the demographic changes or it could be some other trigger which would reignite the conflict.

Socialism or repartition

The road of sectarianism is ultimately the road to civil war. The unionist ambition to tie Catholics to a permanent acceptance of partition is unrealisable. Increases in the Catholic population and the growth of nationalist culture will add to nationalist confidence. The inability of capitalism to eradicate the poverty from Catholic working class areas will mean an irrepressible desire for change.

On the other hand, the nationalist idea that unionism will be driven back by the relative decline of the Protestant population to the point where they will have to raise their hands in surrender and accept Dublin rule is an even greater illusion.

The present situation is like a tug of war with unionists trying to draw Catholics into the existing state and nationalists trying to pull Protestants into a united Ireland. The peace deal is the product of a certain stalemate in the contest. Looking to the future, demographic change makes it impossible for unionism to win outright. But if nationalism should become too strong to hold back the Protestant reaction would be simply to let go of the rope.

Were demographic changes to bring about a majority vote in favour of a united Ireland the result would be civil war and the outcome of a sectarian civil war would not be reunification but repartition. It is important to understand this because it is not uncommon today to hear workers who back the deal say that if it doesn’t work the only other option is civil war. There is even an illusion that civil war would lead to a victory by one side and sort the problem out.

In Bosnia there was a horrific conflict followed by a UN inspired deal which has solved nothing. There is now the potential for events in Kosovo to ignite an even more bloody conflict in the region.

A series of wars in the Middle East have merely created new antagonisms and the latest impasse in what is left of the peace process could end with a declaration of independence by Palestinians and a new war.

The complete breakdown of the Agreement and a movement towards civil war and repartition might leave the ruling class with no option but to recognise the reality being implemented on the ground and draw up lines of separation Bosnia style. Should this happen it would be the working class, Catholic and Protestant, North and South, who would be the main losers. It would not bring stability but new accumulated grievances which, in the absence of any alternative, would weigh on future generations in the way that partition, unionist misrule in the north and nationalist misrule in the south, have come to weigh on the current generation.

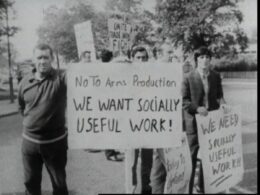

There is only one way out for the working class. It is not to imitate the leaders of the trade unions and sit back and applaud the Agreement and the politicians who produced it. Rather it is to begin to build an alternative to sectarian politics, to unite working people, Catholic and Protestant, around common class interests and in opposition to all who attempt to maintain sectarian division. The urgency with which this is done can only come from an understanding that ultimately the choice facing the working class in Ireland is a choice of either socialism or repartition.

A new class movement

The working class enter into this situation weakened by defeats and by a leadership which has moved to the right and abandoned any idea of struggle. The levels of participation in the trade unions are historically low. This situation can now begin to change and, depending on whether sectarian conflict escalates, confidence in the ability to fight back can return to the workplaces.

World factors are critical in this. The collapse of the Asian tigers and the threat of the effects of this Asian “flu” on the rest of the capitalist world have already gone some way to wiping aside the illusion in the market which flowed from the collapse of Stalinism.

Across the globe there are signs that the working class is again taking to the road of struggle. Revolution looms on the horizon in Indonesia. The Australian dockers have won an historic victory over union-busting bosses. Denmark has been paralysed by a general strike. The disputes in Ryanair and on the Dublin building sites show a level of militancy and confidence among workers in the South. In Britain disillusionment with the Blair government will translate into action at some point and, again depending on the scale of the sectarian conflict, the mood of militancy will spill over into workplaces in the north.

From a working class point of view the best scenario is that the Agreement would hold, that a new local administration would form and that as many as possible of the existing parties accept the ministerial reins they are offered.

On the one hand this would allow the working class movement the precious ingredient of time to begin to put an alternative to these parties in place. On the other hand the fact of these parties holding responsibility for local services and for the low pay, contracting out and privatisation which goes with them, would be a positive assistance to the development of a class opposition.

Since Stormont was prorogued in 1972 there have been many powerful class movements in the North. Apart from the mobilisations against the killings these have almost all been against the policies of the Westminster government. In many cases the local politicians have made a point of showing their faces at demonstrations, even on picket lines, have spoken at workers’ rallies opposing closures, all the time able to point the finger of blame at Westminster. It would be a different matter if these same politicians were responsible for the attacks, cut backs and closures. There would be a local focus for working class opposition. United class movements directed against local politicians would open the way for political conclusions to be drawn, for socialist ideas to begin to take on flesh.

A more drawn out perspective for the Agreement, together with a new impulse to the class struggle, might also throw the tendencies to separation which have been dominant in recent years into reverse. The sectarian parties will seek to obstruct and prevent any real coming together of the working class communities but the instinct to unity from below can be extremely powerful. It is this instinct which has preserved shop floor unity and allowed workplaces to remain integrated, despite being repeatedly put under strain.

But the most important factor in shaping the future will be the direction taken by the new generation of youth. It was the wave of youth who took to the streets after 1968 who changed the course of history and turned Northern Ireland politics upside down. Whether the next generation will get caught up in a new spiral of sectarian violence or whether they will be the engine of socialist change is not yet determined.

Whatever way society moves, whether towards sectarian conflict or towards a socialist solution, it will be through tumultuous events that the path of history will be plotted. Huge and dramatic events will shape and reshape the consciousness of the new generation. Forces and obstacles which today appear unshakeable, the various sectarian forces included, can be melted down in the furnace of struggle. The building of a socialist organisation which can inf1uence and effect events can be a crucial factor in determining whether the coming political and social upheaval leads towards a “carnival of reaction” or towards united class action to bring about socialist change.

A socialist programme

The Socialist Party are the only group on the left whose position on the national question has been updated to take account of present day reality. Most other left groups have what is in reality a left republican position. By holding to this at a time when all but the most backward sections of the republican movement have moved on will leave them standing with these people in an historical time warp.

Socialist Party members, on the other hand, can have great confidence that our analysis offers the only explanation and that our programme offers the only way forward. If we now go on the offensive against the outmoded and, at bottom, sectarian ideas which abound on the left and convincingly put our alternative forward we can make important gains on this issue.

The national problem is not a problem of a single sectarian state in the North which must be destroyed. Partition resulted in the setting up of two sectarian states, one in the North and the other in the South. This description is no longer entirely accurate given the changes introduced to both states over the last quarter century. More accurately the problem is now of two poverty ridden states each with features unacceptable to one or other section of the working class.

Neither can the problem be reduced to the issue of a discriminated against Catholic minority in the North. There are now two minorities, each with a dual element in their consciousness. The Catholic minority retain the sense of being an oppressed group who have suffered discrimination and repression. But they also have a growing sense of being a force on the up, and of being part of an overall nationalist majority in Ireland, a majority which has the wind of world opinion at its back.

Protestants in part inherit their present consciousness from the days when they were the undisputed ruling majority within the north. But increasingly they have a sense of being a minority in the face of this international pressure and with aspects of politics now undisputedly on an all-Ireland basis.

Awareness of democratic changes and of the obvious territorial retreat gives an increasingly beleaguered edge to this minority consciousness. Socialists who recognise only the rights of one community and ignore the other will fall flat on their face on this issue.

The Socialist Party position is to weigh equally the rights of both communities and to expose a solution which guarantees no coercion of either. This cannot be done on a capitalist basis. Only on a socialist basis can basic democratic and national rights be guaranteed.

Socialism means the common ownership of the big industries and finance houses. By taking this wealth out of the hands of the profiteers and speculators and placing it under the democratic control of the working class it would be possible to create wealth and direct resources so as to end exploitation and for the first time in history to eradicate poverty. Guaranteeing to every citizen the right to a decent life free from need is the only way to create the necessary social stability and security to allow the national question to be peacefully and democratically resolved.

Under socialism the administration of society would also transferred downwards, into the hands of the people. Socialism is the antithesis of power removed to distant parliaments or “fire-walled” political institutions over which ordinary people have no real control. It means the maximum devolution of control to democratically established and representative institutions at regional and local level. It means the right of people to change their representatives at any time, through the right of recall, not once every four or five years. Crucially it means cutting the working week so that working people have both the energy and the time to take part in the running of society, and don’t have to leave this to the “professional” politicians.

A socialist government would guarantee the rights of all minorities, including their cultural and linguistic rights. This goes not only for Protestants and Catholics but for all the other racial, national and religious minorities in Ireland. It would uphold every individual’s right to free expression of his or her national culture, but not their right to impose that culture on others.

Socialists are opposed to the idea that a state or a nation must have a single “national” culture to which all its citizens are expected to comply. In the same way we oppose the reactionary idea of any nation having an established religion.

A real solution

The way to solve the national question is to build unity between the working class in common struggle against the present rotten system and for such a socialist society. In reply to those who say “first solve the national problem, the class struggle must wait” we say “there is no solution to the national problem other than through the class struggle”. We stand for the unity of the working class to achieve a socialist Ireland as part of a democratic and voluntary socialist federation of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

We think that this idea could answer the fears and concerns of both Catholic and Protestant workers, but we underline this with the idea of no coercion of either community. Guaranteeing the rights of the two minorities means opposing equally the coercion of either into a political arrangement to which they are clearly opposed. So we would oppose the continued incorporation of the Catholic minority into a separate northern state if their wish is to leave. Likewise and in equal measure we are opposed to any attempt to coerce the Protestants into a united Ireland against their will.

It is impossible to guarantee both these rights on a capitalist basis. This is why the problem cannot be solved without getting rid of this system. On the basis of socialism, which could only come about through the building of unity between workers north and south, and which therefore presupposes a degree of reconciliation, the precise administrative arrangements within Ireland could be agreed peacefully through negotiation.

The Socialist Party believes that the simplest and best solution would be a single socialist state, with maximum devolution. However, should a majority of Protestants remain visibly opposed, the guarantee of no coercion means their right to opt for a state of their own and the building of a socialist federation which would include two states in Ireland.

Those in Catholic areas would in turn be guaranteed the right to opt for either state. This would not be the best outcome since a division of this nature would inevitably draw Catholic and Protestant apart. But it would be up to the people to decide free from intimidation or coercive pressure.

Surrounded by the warring drumbeats of nationalism and unionism and mired in the poverty of a failed economic system this alternative and solution offers a unique way forward for the working class. The Socialist Party is proud of the forces we have built and work we have carried out in advancing our cause North and South. Our greatest force, however, is the power of correct ideas. Our ideas and programme on the national question can now be a powerful lever in the building and development of our party.