By Jess Spear

Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the American presidency was without doubt the biggest political movement in the US in the past 30 years. It inspired millions of people to get active and organized to fight for radical change. After nearly a decade since the economic crash of 2007/8, millions of homes lost, lives destroyed, services left underfunded, and a joyless and uneven recovery, Sanders’ message of the billionaires hoarding all the wealth while we suffer declining living standards hit home.

It lit a fire amongst young people and activated thousands of workers who had never been involved in politics before. It spoke to the real frustration so many people felt towards politics as usual, offered a cogent explanation for why the political establishment was unresponsive to the desires and needs of the vast majority, and appealed for people to stand and fight together.

“This campaign was never about electing a president…this was about understanding that real change never takes place from the top on down. It always takes place from the bottom on up…when ordinary people, by the millions are prepared to stand up and fight for justice.”

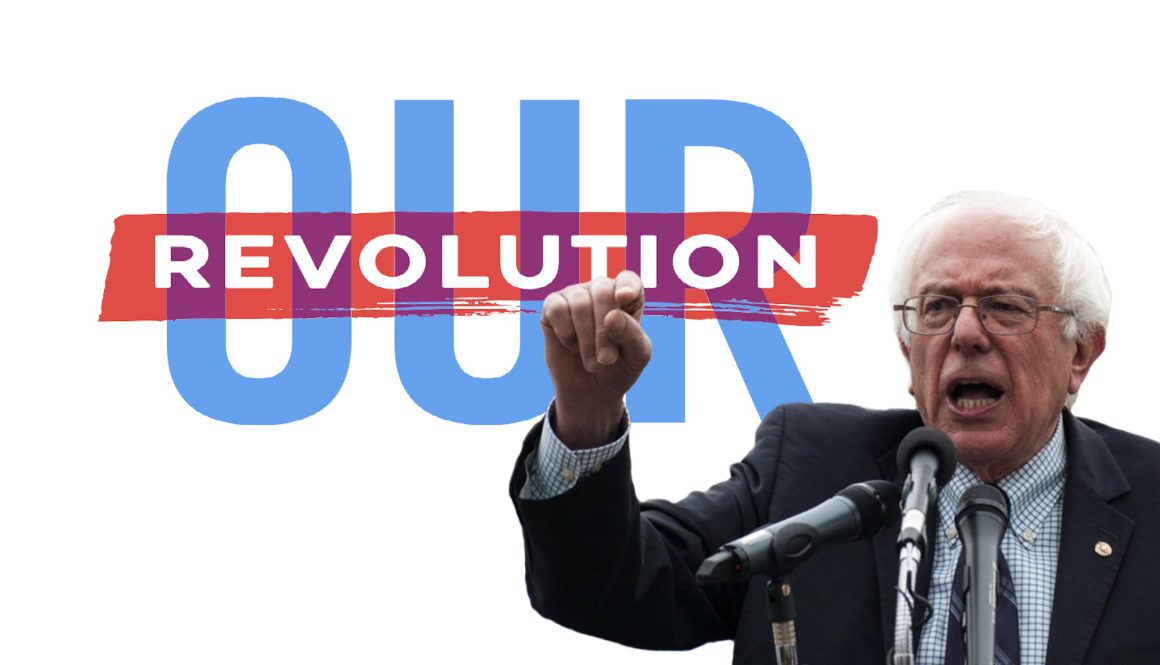

In Our Revolution Sanders tells two stories. The first describes the personal and political experiences that shaped Sanders as a person and politician, from childhood through to his decision to run for president. The second is about that historic campaign. Both are instructive and illustrative of the massive potential for working class politics when clearly articulated and based on building a grassroots movement, as well as revealing some of the limitations of reformism, the idea that capitalism can be reformed for the better.

“How do we turn out the way we do?”

In the first chapters, Sanders runs quickly through the main events in his childhood that influenced his world outlook, from his Jewish heritage to learning how children are affected by the wealth of their parents,

“How much money your family had determined the quality of your baseball glove, which brand of sneakers you wore, and what kind of car your father drove.”

In college he learned real American history, “I learned that America was not always “the land of the free and the home of the brave” and that our country was not always on the right side of history.” He joined political organizations: Young People’s Socialist League (the youth wing of the Socialist Party of America), the Student Peace Union, and the Congress of Racial Equality and “learned to look at politics in a new way. It wasn’t just that racism, war, poverty, and other social evils must be opposed…. There was a relationship between wealth, power, and the perpetuation of capitalism.”

After college, almost by accident, he became involved in third party politics when he accepted the invitation of a college friend to come along to a meeting of the Liberty Union Party, a small socialist party in Vermont that was founded only the year before. It was at that meeting he was nominated to run for Senate, and subsequently ran four more times as a LUP candidate before resigning and eventually running as an independent.

Sanders’ experience as an independent, first as Mayor of Burlington, Vermont (the only socialist mayor in America), then Congressman and eventually as Senator, demonstrates the entrenchment of the two party system and how it functions to narrow the debate. Not only did the two parties conspire to sabotage his tenure as Mayor, looking to prove he was ineffective, but once in Washington the Democrats were reluctant to assign him to any committees.

To run, or not to run

Sanders was first asked about running for president during an interview with Playboy magazine in 2013. He lays out four reasons that motivated his eventual decision: 1) “was it good for democracy” that Hillary Clinton was “anointed as the Democratic nominee…without opposition?” 2) If he didn’t run, who would? 3) the waters could be tested before deciding, and 4) he wanted to see if his progressive ideas would resonate outside of Vermont.

For 18 months, Sanders toured the country, focusing heavily on the states that vote early in the primaries, and “tested the waters.” Over that time it became clear that his initial predictions were correct. “People…were hurting…were tired of the status quo…didn’t want Hillary Clinton,…wanted real political change—and were prepared to fight for it.”

For socialists, though, the key strategic question for Sanders to address was not whether to run, but under what banner. Was Sanders going to stand independently of the Democrats, or not?

Despite what many believe, the Democratic Party has never been the party of, by, and for the American working class. It has always been a political tool of the ruling class (first the slave owning class, then the capitalists). At times (under Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) especially, but also under the Lyndon Johnson administration) it, along with the Republican Party, has been compelled to bend to the will of mass movements powerful enough to threaten the rule of the capitalists. And, in order to carve out electoral space, it has professed to support pro-worker, pro-environment, and pro-Keynesianism policies that favoured state investment in the economy. However, as Sanders’ own political career aptly demonstrates, the Democratic Party actually operates in the interests of corporate America, and since Bill Clinton’s presidency in particular, it has unrepentantly embraced neoliberal policies.

Socialist Alternative (sister party of the Socialist Party in the US) recognized the enormous impact a Sanders campaign, espousing class politics could have on the increasingly polarized situation developing in America. The rise of Occupy Wall Street, mass environmental battles, the Fight for $15, and Black Lives Matter all pointed towards a growing mood for struggle. The potential to unite these movements under a new banner and build an independent party for workers and youth was never higher. Nearly 60% of people said they wanted to see a new party.

Unfortunately, Sanders didn’t agree. He acknowledges that “some…believed that if I ran it should be done outside the Democratic Party, with the goal of building a new political movement. While this was a minority opinion, it surfaced frequently.” Unfortunately, he never says why he ultimately decided against it.

It seems likely he was motivated to run as a Democrat by a number of factors, including the fact that he had no party of his own to rely on for organizational infrastructure, a number of Democratic-affiliated groups had enthusiastically indicated they would work for his campaign, and ultimately his own experience in Washington demonstrated the difficulty in breaching the walls of the two party fortress. What Sanders failed to recognize is that his grassroots campaign had enormous potential to begin coalescing the forces to not only breach the walls, but to smash that fortress entirely.

Run until November

Much could be said about all that occurred during the presidential race. The phenomenal numbers who donated, over and over again, helping to raise a record breaking $232 million, blow out of the water any argument that you have to rely on money from big business to win. For the tens of thousands newly active in the Sanders campaign, the lack of media attention was a real education on the role of the media in shoring up establishment politics and ensuring grassroots movements are ignored.

However, what is most striking and noteworthy is that it ended, and it didn’t have to. When Sanders ended up endorsing Clinton, he had won 22 states, more than 13 million votes, and was polling better than Clinton against Donald Trump. Knowing what you know now, it’s hard not to hark back to a point Sanders’ makes early in the book:

“The message is key to any serious campaign, but the message doesn’t matter much if nobody hears it.”

The vast majority of people don’t pay attention to the primary campaigns. While Sanders attracted the attention of possibly millions who would have otherwise tuned out, there is no doubt that a much larger section of the population never heard his campaign speech, never heard his debates with Hillary, and didn’t know about this growing movement for a political revolution.

Had he continued on as an independent (a real possibility offered by the Green Party), his message would have been heard by tens of millions more workers. He likely would not have won, but the project of building an independent party to fight for workers, women, people of colour, LGBTQ, immigrants, and the environment would have been considerably advanced.

“The struggle continues”

Since Trump’s election, Sanders has been his most prominent and effective political opponent. Unlike the rest of the Democratic Party, Sanders opposes Trump by not only exposing Trump’s plans to aid the very wealthy, but also by continuing to campaign on the issues he ran on – $15 minimum wage, free tuition at public colleges, medicare for all (a free national health service) and a trillion dollar jobs programme. Through this he’s peeling away support from Trump’s base.

His activity since Trump’s election shows that he still feels strongly that working-class people and the oppressed can be united behind his program. During the healthcare debates in March as Democrats held rallies to defend Obamacare, Sanders went to conservative voters in West Virginia – one of the poorest states in the country that voted for Trump.

In McDowell County, he spoke to former miners and their families about what the Republican plan – “Trumpcare” – would mean,

“At a time when we have a massive level of income and wealth inequality, this legislation would provide, over a 10-year period, $275 billion in tax breaks to the top 2 percent…”

At the same time, he has channelled the majority of his supporters towards reforming the Democratic Party through Our Revolution (the organization). This grassroots-focused organization seeks to elect progressive democratic candidates (“Berniecrats”) at all levels of government as well as reforming and revitalizing the Democratic Party in the local precincts.

The first major test for the reform movement was a contest between former Obama Labour Secretary Tom Perez and Keith Ellison whom Sanders backed for the Democratic National Committee Chair. It was a close race, but ultimately Perez won. The bitter defeat left many new “Berniecrat” activists feeling demoralized. Ellison’s loss revealed the Mt. Everest in front of them.

“Break through those limitations”

The corporate leadership of the Democratic Party is not going to give in easily. Ultimately, they are the political tool of a social class, well-honed to ensure their continued profits. Transforming the party to actually be of, by, and for working people would mean ending all corporate donations, consistently fighting for pro-worker and pro-environment policies, a binding platform, and crucially, democratic structures that allow for the membership to hold their representatives accountable. In other words, it would take an almighty battle with the corporate leadership and that social base.

But, who is going to join in that movement? There’s no doubt that thousands of people have become activated in this project. But the Democratic Party banner is completely tarnished from decades of betrayals for the millions more needed. Ultimately it was Bernie and his programme that garnered so much attention and support over the last two years, not the project to reform the Democratic Party.

Crucially, there lacks a serious recognition of what might happen if a movement of millions was actually mobilized to change the Democratic Party. Even the limited openings in the Labour Party in Britain, which allowed Corbyn to become leader, don’t exist within the Democrats. The same machine which sabotaged Sanders’ campaign would use its formidable power to prevent any insurgency which threatened the corporate leadership. A new party, independent of big business, solves the first problem and thereby draws together the necessary forces to carry out a political revolution.

The Sanders platform got people moving and activated young and working people in a left movement. It got them believing they could change their lives and country. In that respect, his program was radical. But, once you get people moving, the question immediately posed is, where to next? How far should does the struggle to change society need to go?

Fundamentally Sanders is for a limited struggle over the wealth in society, writing “I don’t believe government should…own the means of production.” Yet, even Sanders’ limited programme, which would take even just a small portion of the wealth at the top, has already met fierce resistance from the ruling class. Just as his organising strategy under-estimates the political opposition of the Democrat Party elites, his political programme under-estimates the class opposition of the ruling 1%. Only a battle carried to the end, including taking into democratic public ownership the top Fortune 500 companies, could deliver the revolution which those who look to Sanders seek.

Bernie Sanders is currently the most popular politician in the country, with an approval rating at roughly 60% (while Trump hovers around 40-45%). The most trusted politician, in the heart of global capitalism, is a self-avowed socialist. That fact alone encapsulates the potential for left wing and socialist ideas to gain mass support.