By Manus Lenihan

The Maurice McCabe scandal has been another grim reminder that we don’t have a “free press” (in the true sense of the word) here in Ireland. Rather we have a media that in general has an overly-cosy relationship with the establishment. With the McCabe scandal, it’s clear that big sections of the media cooperated with the mafia-style “code of silence” under which McCabe became a marked man for speaking out.

Under capitalism, there is a ruling class or “establishment”: big business owners, the rich list, top civil servants and politicians, and the high-ups in state bodies. The media, which is one part big business (e.g. Denis O’Brien, the Murdoch press) to one part bureaucratic state bodies (eg RTÉ), is an intrinsic part of this establishment, not a power that can consistently hold it to account. The formal and informal links are too strong – one key problem being that journalists often become mouthpieces in order to keep their sources sweet.

A deafening silence

One example from the McCabe scandal was when RTÉ’s Paul Reynolds leaked a report that Justice Kevin O’Higgins had called McCabe “irresponsible” and “a liar” – a leak that was very convenient for the Gardaí.

We have learned that the Gardaí did a ring-around of the media, trying to peddle the lie that McCabe sexually abused a child. No journalist would print the story because they knew that it wouldn’t stand up. But in media circles, just like in Leinster House, many journalists knew about this blatant, disgusting smear campaign and didn’t publicise it. It’s as if this is just how they expect the Gardaí to carry on.

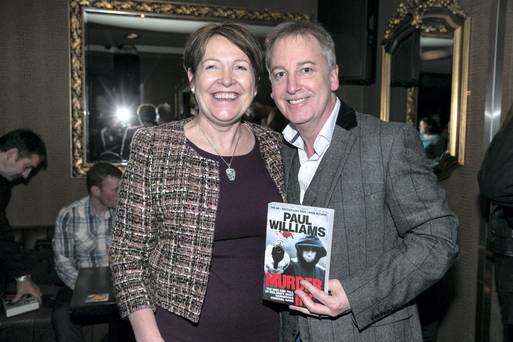

Crime correspondents in particular are now feeling the heat. At the centre of the criticism is Paul Williams, crime correspondent for the Sunday World, whose reporting on the Shell to Sea protests in Rossport, Co.Mayo was notoriously partisan on the side of the Gardaí. In the McCabe saga, Williams even went so far as to print the grotesque innuendo – although without naming him.

One unnamed journalist, in the context of defending his profession, admitted that some crime journalists “have made a career out of” being mouthpieces for the Gardaí. Another lamented that getting basic information from the Gardaí was like “pulling teeth.” (Irish Times, “Crime Reporters Object to Negative Image of their Trade”, Feb 10).

The media and Jobstown trials

Of course, it’s not a shock to most people that the media are playing this role. We saw how RTÉ and the newspapers repeatedly announced the death of the water charges movement – only for the next big protest, boycott or electoral shock to catch them unawares.

We saw how the media attacked the Socialist Party, the AAA and the people of Jobstown after a sit-down protest delayed Joan Burton in November 2014. We saw lies combined with hysterical opinion pieces and headlines. Mud was slung indiscriminately. They didn’t say a word about the thuggish behaviour of the Guards on the day. Ruth Coppinger was vilified despite not even being there, just because she publicly defended the right to protest.

Paul Murphy was grilled by everyone from George Hook to Ryan Tubridy. All in all, the media whipped up a climate where Murphy, AAA councillors and members and other widely-respected activists are on trial on absurd charges and could face serious jail time. The behind-the-scenes consensus of the ruling class – that a sit-down protest was now redefined as “false imprisonment” – was transmitted seamlessly to the media as well.

It’s funny now to remember how George Hook was outraged when Paul Murphy said that the Gardaí were engaged in political policing after Murphy was taken from his bed at dawn in early 2015. Hook insisted that the Guards were spick-and-span and completely independent of politics. Now this would appear ridiculous even in the eyes of the most complacent journalist.

But it’s not just George Hook or Paul Williams – most of “respectable public opinion” in Ireland comes out of this scandal looking very bad. The McCabe saga has revealed some of the ways in which the media functions as its Public Relations wing.