By Manus Lenihan

In September 1921 the workers at the port of Cork city went on strike. They occupied the port and Bob Day, the union organiser, addressed the strikers as “Friends, comrades and Bolsheviks.” Day went on to explain what he meant by the word “Bolshevik”: a desire “that the bottom dog should go up and the top dog come down.”

That was what had happened in Russia in 1917. The top dog, the Tsar and the bosses and landlords came down, and the workers, led by the Bolshevik Party, formerly the bottom dog, became the ruling class for the first time in history. As Day’s words reflect, this was a massive inspiration for the “bottom dog” everywhere, including Ireland. This year we mark a century since these earth-shaking events.

Revolutionary wave reaches Ireland

It’s not widely known today, but from 1917 to 1923 there was mass support for the Russian Revolution in Ireland. This was partly because the early Soviet Union championed the idea of self-determination. The idea that a socialist revolution was sweeping the globe appealed even more strongly to toilers in Ireland, with James Connolly a strong reference point for socialist ideas. This was before Stalinism generated a lot of confusion about what the Russian Revolution and socialism actually represented.

Three months after October 1917, 10,000 attended a rally in the Mansion House in Dublin to celebrate the events. The atmosphere was electric, with the crowds spilling out the doors in such numbers that two overflow meetings had to be held.

The newspaper of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) gave massive coverage to early Soviet Russia from 1918 on. In spite of paper rationing, every issue had loads of material on the Revolution. Thousands of workers read the latest statements from Lenin and Trotsky, news of events in the Russian Civil War and descriptions of the revolutionary movements sweeping across the world. These years saw the ITGWU (today SIPTU) grow from 5,000 in 1916 to 25,000 in 1917, passing the 100,000 mark in 1920.

In April 1919 a general strike broke out in Limerick against British military. The name the workers gave to this strike – the Limerick Soviet – signals where they drew their inspiration from. The trades council ran the city for weeks, giving real content to the idea of a worker’s soviet.

From Cork to Belfast and from Galway to Dublin, in cities, towns and villages, we find the marks of the Russian Revolution in this period. Strikes and movements were referred to by their participants as “Soviets”; battles took place between big farmers’ “White Guards” and labourers’ “Red Guards”; and the word “Bolshevik” comes up again and again in the records.

The relevance of the 1917

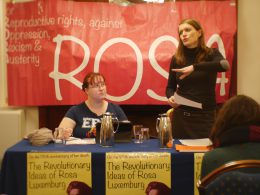

This year the Socialist Party and the Committee for a Workers’ International, the global organisation we’re part of, will be commemorating the events of 1917 and their impact around the world.

Today capitalism offers us a vista of inequality, hatred, war, mass poverty and climate change. A host of writers and commentators will try to portray the Russian Revolution in a negative light – most of them with a bitter agenda of trying to convince people that any attempt to fundamentally change society will end in failure. That’s why we’re eager to reclaim the real memory of what happened, and of how at the time it was correctly viewed by the masses in Ireland as a movement for working-class liberation.