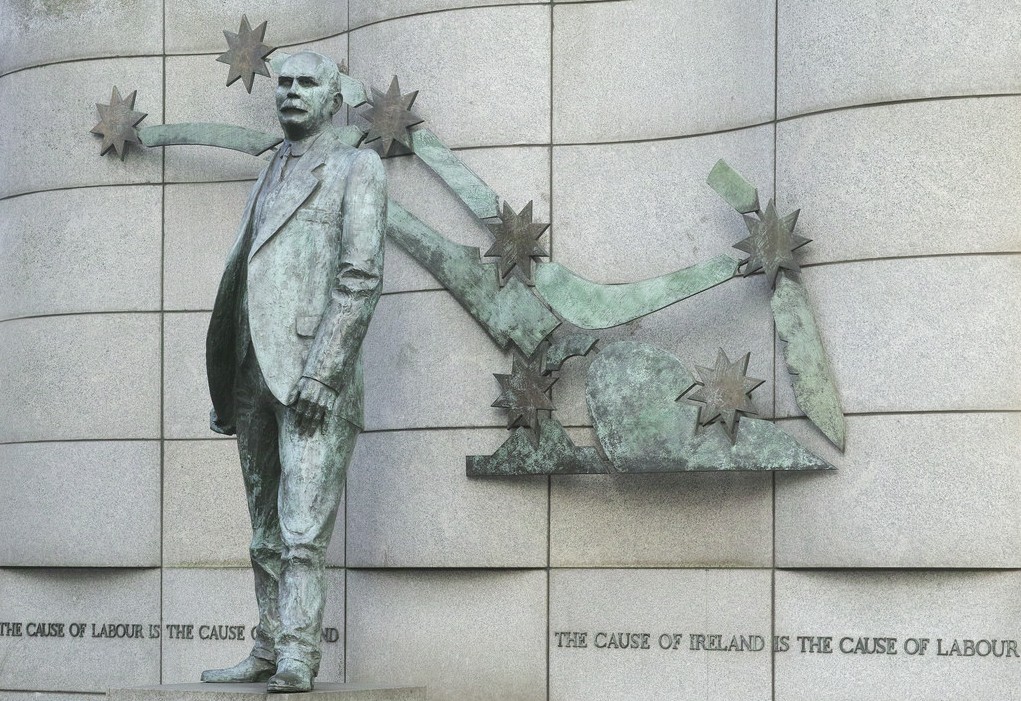

The following article was written by Peter Hadden (who sadly passed away in May 2010) on the 90th anniversary of the Easter Rising and death of James Connolly. The article explores Connolly’s socialist ideas and analysis and his role as a workers leader and socialist organiser in Scotland, the US and Ireland.

IN 1910 JAMES CONNOLLY concluded his pamphlet, Labour, Nationality and Religion, in the simplest and most straightforward terms: “The day has passed for patching up the capitalist system, it must go.” Ninety years after his death it is necessary to begin any true account of James Connolly’s life with reminders of what he really believed in, what he really fought for.

It is necessary because, with this year’s anniversary celebrations of the 1916 Easter Rising, we are likely to witness the nauseating spectacle of Irish government representatives, leaders of the establishment parties in the south along with the main nationalist parties in the north, trying to commemorate and venerate Connolly as though, somehow, they follow in his tradition.

Connolly, were he alive today, would be fighting as relentlessly against these people and the system they represent as he fought against their equivalents in Ireland and internationally in his own time. But he would not be surprised that people who are the enemies of all that he stood for would try to claim his political heritage. After all, in the centenary year of the 1798 Rebellion, Connolly noted the way the establishment of the time did much the same to the memory of United Irish leader, Wolfe Tone. “Apostles of freedom”, he wrote in the first edition of his newspaper, Workers Republic, “are ever idolised when dead, but crucified when living.”

Connolly was born in the Cowgate district of Edinburgh in 1868, the youngest of three sons. His father was a carter and the family lived in extreme poverty. James had to work from the age of ten or eleven. He worked in a printers, a bakery and a mosaic tiling factory. His education was rudimentary and his formidable skills in writing – not just his political and historical journalism but also his attempts to get a message across through poetry and drama – were largely self taught. Desmond Greaves, in his biography of Connolly, surmises that the young James had to read by the light of embers, “whose charred sticks served him as pencils”. Hence his slight squint. Connolly was also slightly bow legged as a result of rickets, a common by-product of poverty and malnourishment.

He was only 14 when poverty forced him to adopt a pseudonym and enlist with the King’s Liverpool Regiment of the British Army. His service took him to Ireland and lasted almost seven years before he deserted and returned to Scotland at the end of 1888 or early in 1889. It was then that, scraping by through casual work in Edinburgh, Connolly began his lifelong involvement in socialist politics. He joined the Socialist League, a split from the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), one of the earliest socialist groups in Britain. Members of the Socialist League included Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl Marx, and one of its main influences was Frederick Engels.

All the groups that existed at the time were very loose and federal in structure and there was a constant overlap in membership. By the time he left Scotland in 1896 to take up an invitation to become the secretary of the Dublin Socialist Club, Connolly, although in financial destitution, was the secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation and of the Scottish Labour Party, the local name for Kier Hardie’s Independent Labour Party (ILP).

Within months of his arrival in Dublin he converted the Dublin Socialist Club into the much more organised Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP), formed at a meeting of eight people in a bar in Dublin’s Thomas Street in May 1896. He became its paid organiser at a salary of £1 a week. From that time until his execution twenty years later, Connolly was a full-time revolutionary, working, when the money was there, for small socialist groups like the ISRP or later the Socialist Party of Ireland, or else as an outstanding trade union organiser. For much of this time Connolly and his family continued to live in poverty. Much of the time he was forced to go on prolonged speaking tours to raise funds, to Scotland, England and the USA.

Connolly understood the need for publications to get his ideas across. He produced a number of important pamphlets and published a number of newspapers, notably Workers Republic, first launched as an ISRP publication, and The Harp, a newspaper he first issued in the US, where he lived from 1903-1910.

Maintaining these papers on a shoe string and with a limited circulation would not have been possible but for the gargantuan energies Connolly poured into the task. He was the main contributor, the person who ensured that publication dates were met, printers’ bills paid, and was most often the driving force on sales. Bearing out that the job of revolutionaries is to do what needs to be done, no matter how mundane the task, Connolly took it on himself to see that his papers reached the widest working-class audience. In the US he stood at street corners and outside meetings selling The Harp. One of the early pioneers of the US labour movement, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, in her autobiography, remembers Connolly pushing the sales of this journal: “It was a pathetic sight to see him standing, poorly clad, at the door of Cooper Union or some other East Side Hall, selling his little paper.”

It was through his articles in these journals and in the papers of other organisations that Connolly developed the ideas that he held most consistently through his life. He took the ideas of Marx and Engels, especially their view that the motor force of history is the struggle between contending classes, and applied them to Ireland.

His earliest pamphlet, a series of essays published in 1897 under the title, Erin’s Hope, drew the conclusion that Connolly defended and expanded upon throughout his life, that the Irish working class was “the only secure foundation on which a free nation can be built”. This conclusion was amplified and presented in a more rounded form in his major work, the 1910 pamphlet Labour in Irish History. This booklet remains Connolly’s most important contribution in the realm of ideas.

The main conclusion of Labour in Irish History is that the Irish middle and propertied class “have a thousand economic strings in the shape of investments binding them to English capitalism”. It follows that “only the Irish working class remain as the incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland”. These conclusions parallel the ideas being developed by Leon Trotsky at the time, now known as the theory of the permanent revolution.

Trotsky explained that the native bourgeois (capitalist class) in the less developed countries and in the colonial world had emerged late onto the scene of history. They were too enfeebled as a class to dare to put themselves at the head of movements to remove the last vestiges of feudalism or establish independent nation states as the bourgeois in the established capitalist powers had, nervously and often incompletely, managed to do. These tasks fell then to the working class who, in taking power, would carry through the unfinished tasks that in a previous historical period had fallen to the rising capitalist class. But at same time the working class would proceed, uninterrupted, to carry through the tasks of the socialist revolution.

Connolly never drew these conclusions with the precision of Trotsky. Nor had he the opportunity to read Trotsky’s material. As with many of his other writings, there is occasional ambiguity in his writings on the national question, an ambiguity that was amplified by his actions at the end of his life. He did make statements, especially at that time, which could be read as supporting the idea that independence would give a boost to the struggle for socialism. For example, in 1916 he commented that independence is “the first requisite for the free development of the national powers needed for our class”. Loose formulations like this have been used by some on the left to back the mistaken notion that national independence is somehow a necessary first ‘stage’ on the road to socialism and to justify alliances with nationalists to achieve this.

This was never really Connolly’s view. His most consistent material states the opposite. In Labour in Irish History and in his other main writings on the national question, he is more or less at one with Trotsky; that it is the working class who must achieve independence and, in so doing, will also establish socialism. This made him a giant of his time.

In many other respects Connolly stood politically head and shoulders above those around him in the British and Irish labour movement. He recognised that “every political party is the party of a class” which it uses “to create and maintain the conditions most favourable to its own class rule”. The working class needed its own political instrument and this instrument should stand independent of other parties.

It goes without saying what his position would have been on the present day calls of trade union leaders for ‘social partnership’; on those like the Irish Labour Party and Sinn Fein who spend their time knocking on the doors of the right-wing establishment parties seeking coalition government; or indeed on those on the left who quietly drop their socialist ideas so they can participate in broad ‘fronts’ with individuals and groups that are fervently hostile to socialism.

The socialist organisations of Connolly’s time were still mainly propaganda organisations without a mass political base or influence. To Connolly this was something to be changed and the question of the hour was how to build them into mass organisations without diluting their socialist content. Intense debates on questions like this raged within all the socialist groupings that Connolly was involved with. There were often very bitter exchanges that reflected different political trends that were emerging. One of his political experiences was with the Scottish wing of the SDF, ultimately a propagandist sect, led by Henry Hyndman, a man whose role, as Connolly saw it, was “to preach revolution and practice compromise and to do neither thoroughly”.

When he left Ireland for the US in 1903, Connolly joined the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) which was led by Daniel De Leon. Connolly soon clashed with De Leon over a number of theoretical questions and more particularly over the dictatorial way in which he ran the SLP. De Leon’s response was not always political – among other things he accused Connolly of being a “Jesuit agent” and a “police spy”. All in all it was a bitter experience and Connolly would have agreed with Engels who, early in the 1890s, wrote that the SDF and SLP treated Marxism in a “doctrinaire and dogmatic way as something to be learnt off by heart … To them it is a credo and not a guide to action.”

Connolly left the SLP in 1908 declaring it had no future in De Leon’s hands, except as a “church”. He joined the Socialist Party, a larger organisation but with a more compromising/reformist outlook, in order to “be one of the revolutionary minority within it”. This demonstrates his total absence of political sectarianism. He knew the importance of clear ideas but he also understood that it was necessary to take those ideas into the living movement of the working class, not refrigerate them in a pure political sect.

At the 1912 Irish Trades Union Congress, held in Clonmel, it was Connolly who successfully moved the motion for independent labour representation that marked the birth of the Irish Labour Party. He saw no contradiction between this and his work to build his own Socialist Party of Ireland. Connolly, in other words, instinctively understood the dual task of socialists to encourage, assist and participate in every development that draws the broad mass of workers into political activity, while at the same time building a more conscious socialist organisation.

This does not mean that he had a clear conception of the need for a revolutionary party that could act as the instrument of the working class in carrying through the socialist revolution. At the time, only Lenin in Russia understood that a successful revolution would require a conscious leadership organised in such a way that it would not bend politically under the pressures of events.

Trade union struggles

CONNOLLY, LIKE MOST of the Marxists of his day, was not fully clear what instrument the working class would use to overthrow capitalism or how. For a time, he put forward the syndicalist view that the main role would be played by industrial unions. His flirtation with syndicalism does not mean that he saw no role for politics or parties. Throughout his life he was consistent on the need for the working class to organise itself politically as well as industrially.

Connolly understood the critical importance of ideas. But he would never have been content to play the role of a dusty, De Leon style, professor. He understood that theory is only a preparation for action and that the only real testing ground for ideas is in the living movement. During the last decade of his life in particular, most of which he spent working as a revolutionary trade union organiser, his ideas and his methods were put into practice in a series of momentous struggles and upheavals.

His ability as a mass workers’ leader was put to the test in Ireland in 1911 when he became the Belfast organiser of James Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU). He had returned from the US with several years’ experience working as an organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World. During this time, he had participated in some of the bloody battles that were being fought by US workers against vicious bosses backed by armed police and scabs.

Connolly took up his position in the ITGWU just as an explosive wave of strikes was taking place in Britain and Ireland. Three million strike days were lost in 1909. Three years later the figure was 41 million. Ireland saw the most bitter battles as employers tried to forcibly resist the militant growth of New Unionism, the organisation of the semi-skilled and unskilled, in the form of the ITGWU. In 1911 Connolly led a struggle of the Belfast dockers. That was quickly followed by an approach from female mill workers, the “linen slaves of Belfast”, and an inspiring strike by more than 1,000 of these workers against the grim conditions and tyrannical managerial regime they suffered in the mills.

At the end of 1911 Connolly had to go to Wexford where ITGWU members had been locked out since August in an attempt by employers to break the union. During this dispute, the workers formed a defence organisation, a ‘Workers Police’, to protect themselves from the police. This was a forerunner of the Irish Citizens’ Army which was formed for the same reason during the 1913 Dublin lock out.

Dublin 1913 was the culmination of this period in which the forces of labour and capital went head to head in Ireland. In August 1913, the Dublin Employers’ Association, led by William Martin Murphy, locked out ITGWU members, demanding they leave the union. This was a bid to finally break the back of the Irish labour movement before a Home Rule parliament was established.

The struggle dragged on until the end of January 1914 when the workers were finally starved back to work. At its highpoint, it involved virtually the whole of the Dublin working class. The undisputed leaders of the workers were Larkin and Connolly. Arraigned against them were not just the employers and the forces of the capitalist state, but the churches and the forces of right-wing nationalism. Lenten pastorals from the pulpits denounced socialism and trade unionism. The Ancient Order of Hibernians – Ancient Order of Hooligans to Connolly – who from the early days of the ISRP had been involved in repeated attempts to physically break up Connolly’s meetings and rallies, broke into the Irish Worker printing office and smashed the type.

In the end it was the false friends rather than the open enemies of the ITGWU who left the workers of Dublin isolated and with little choice but to return to work. Connolly and Larkin had called for a solidarity general strike in Britain and for the blacking of the scab boats that were delivering goods in and out of the port of Dublin. The issue of blacking was debated at a special meeting of the British TUC in December but, with the leaders of the main unions opposed to solidarity action, the motion was decisively defeated by 2,280,000 votes to 203,000.

The eventual return-to-work was on the employers’ terms but the immediate victory they had won was at the cost of laying down a tradition of militancy and solidarity which meant that the union had been badly wounded but not broken.

The national question

THIS WAS ONE of three defeats suffered by the working-class movement in the space of a few short years, which without a doubt left Connolly somewhat disorientated and shaped the direction he took in the last three years of his life.

Connolly’s return to Belfast after the strike was against the backcloth of the Home Rule crisis of 1912-14. The proposal by Westminster to grant limited Home Rule to Ireland had invoked a furious opposition among Unionists and from a significant section of the British ruling class. The Ulster Volunteer Force was formed in 1913 and the Unionist hierarchy voted to establish a provisional government in Ulster in the event of the Home Rule Bill becoming law. With the drums of civil war beating loudly a compromise was arrived at that allowed for the ‘temporary’ exclusion of any of the Ulster counties that chose to stay out of the arrangement. Nationalist leader, John Redmond, accepted this deal.

Connolly dismissed the idea that this exclusion would be temporary and correctly viewed these events as a defeat for the working class. He predicted that partition would “mean a carnival of reaction both North and South, would set back the Irish labour movement, and paralyse all advanced movements while it endured”.

During his time in Belfast, Connolly had attempted to unite workers both industrially and politically. But he did not manage to give the unity achieved in strikes and other struggles a lasting organisational form. The ITGWU organised Catholic workers in the main, as did the socialist political groups with which he was involved.

Connolly stood for class unity and fought to achieve it, but this fine ambition in itself was not enough to break the sectarian mould. He never properly examined the reasons why big sections of the Protestant working class were prepared to fall in behind the Lords and Ladies of Unionism. If he had looked more closely he would have seen that Protestant workers had real fears about what might happen under a Home Rule parliament and would have understood that it was necessary for socialists to put forward ideas to counter those fears.

The greater Belfast area was the industrial hub of Ireland at the time. The heavy industries that had developed were part of an industrial triangle whose other two points were Liverpool and Glasgow. Protestant workers had developed strong ties of struggle with workers in these cities especially. Their fear was that in a Home Rule parliament, run in the interests of the smaller businesses in the south who favoured protectionist measures, their ties with the labour movement in Britain would be broken and their jobs would be threatened as their industries were cut off from their export markets.

Connolly’s analysis of the national question as it had evolved in Ireland was fundamentally correct, but his application of that analysis in the form of a programme was somewhat one-sided and, as such, would not re-assure the mass of Protestants. Along with Larkin, he stood for separate Irish trade unions as well as separate political organisations. This was necessary in order to draw Catholic workers away from the Nationalists. But in the north it created the danger, as actually happened, that Protestants would, by and large, stay with the British organisations and workers would be divided along religious lines. At the very least, it would have been necessary to advocate that special formal links be maintained between the working class organisations in Ireland and in Britain, and especially to defend and maintain the ties that had been built up between shop stewards’ organisations.

Likewise on the question of independence. Connolly was correct in advocating an Irish Socialist Republic, but this too was posed in a one-sided manner. When Marx spoke about the struggle for Irish independence, meaning independence on a capitalist basis, he added the rider that after independence “may come federation”. Connolly’s material leaves this idea to the side.

While fighting to place the labour movement, with its goal of a socialist republic, at the head of the struggle for independence, it would have been better if Connolly had also argued to maintain the links with the British working class and had put forward as the ultimate objective the idea of a voluntary socialist federation of Ireland and Britain.

World war & the Easter rising

THE THIRD DEFEAT suffered by the working class came in the form of the outbreak of war in August 1914. Before the war, the mighty parties of the Second International, particularly the Social Democratic Party of Germany, had issued belligerent anti-war statements and had promised a general strike to paralyse the war effort should hostilities be announced.

When the fighting started, all this resistance, with the exception of some courageous individual leaders and of a few parties like the Russian Bolsheviks, crumbled away to nothing. To Connolly this was another blow and he responded in his typical vituperative style: “What then becomes of all our resolutions, all our protests of fraternisation, all our threats of general strikes, all our carefully built machinery of internationalism, all our hopes for the future? Were they all as sound and fury, signifying nothing?”

The outbreak of war was accompanied by a wave of jingoism. Class ideas along with strikes and other expressions of class struggle were, for the moment, pushed to the background. In Ireland, Nationalist leader John Redmond, became a voluntary recruiting sergeant for the British army and tens of thousands who had previously drilled in the uniforms of the Irish volunteers joined up.

It is clear from Connolly’s writings after 1914 that all these disappointments and betrayals affected him deeply. His writings on the war, as a whole, were not so clear and precise as earlier works. At bottom he maintained his socialist and internationalist outlook but, increasingly, his ideas became tempered by his frustration at the passivity of the working class in face of the slaughter in Europe: “Even an unsuccessful attempt at social revolution by force of arms, following the paralysis of the economic life of militarism, would be less disastrous to the Socialist cause than the act of Socialists allowing themselves to be used in the slaughter of their brothers in the cause. A great continental uprising of the working class would stop the war”.

With England so heavily preoccupied, he began to consider that the first blow could be struck in Ireland. As the war bogged down to the seemingly interminable horror of the trenches, the need to act quickly to ensure that this blow was struck became his overriding concern.

In his impatience he was prepared to set some of the ideas and methods he had so carefully developed during a lifetime of revolutionary struggle temporarily to the side. In Labour and Irish History he points out correctly that “revolutions are not the product of our brains, but of ripe material conditions”. In an earlier Shan Van Vocht article he criticised the Young Irelanders and Fenians for taking to the field when the conditions for revolution had not matured: “The Young Irelanders made no reasonable effort to prepare the popular mind for revolution so failure was inevitable.” Now he stressed the opposite argument, criticising those in the Young Ireland movement who talked about revolution but when the time came “began to make excuses, to murmur about the danger of premature insurrection”.

With the working class largely quiescent, Connolly looked to the radical nationalist forces then organised in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and the 13,000 Irish Volunteers who had broken from Redmond over his support for the war. He hoped that an uprising in Ireland, even if it was organised for nationalist rather than socialist objectives would, as he put it, “set the torch to a European conflagration that will not burn out until the last throne and the last capitalist bond and debenture will be shrivelled on the funeral pyre of the last war lord”.

In order to pressurise the IRB, and through them the Volunteers, into action, Connolly was prepared to make political concessions he would not have made at any other time in his life. He was fully correct to work alongside the nationalists in opposition to the war as he did in the Irish Neutrality League. But in joining hands on specific issues it was also necessary, as Connolly had done throughout his life, to maintain an organisational and political independence. Connolly never abandoned his socialist ideas but there were times when, by not putting them forward, he allowed his views to be blurred with those of the nationalists. It was the green flag of independence, not the red flag of socialism, not even his own Starry Plough, that he flew over Liberty Hall, the ITGWU headquarters.

The conditions for a successful rising did not exist in 1916. From this point of view the rising was premature and doomed to failure from the start. Connolly was aware of this. When, on the morning of the rising his long-term colleague William O’Brien passed him on the stairs of Liberty Hall and asked if there was any chance of success, Connolly’s reply was “none whatsoever”.

For Connolly its purpose was as an act of military defiance whose repercussions would hopefully reverberate around the other European nations and encourage the working class of other countries to rise. His lack of any real attempt to use his position at the head of the ITGWU to prepare the working class to back the rising shows that he was only too well aware that there was no broad mood of support for what he was about to do. He made no call for a general strike to paralyse the movement of troops and munitions. During the rising itself he made no attempt to appeal to the British troops on a class basis not to fight.

Leaving aside the issue of whether it was correct to go ahead at this time, the manner in which Connolly participated was also wrong. In his desperation to make sure that the rising went ahead he agreed to participate largely on the political terms of the Volunteers, rather than his own.

He put his name to the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, which was read by Pádraic Pearse from the steps of the GPO. The proclamation is a straightforward statement of nationalist, not socialist ideas. It is true that there are phrases in it that were most probably insisted on by Connolly, such as the declaration of “the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland”. Connolly had previously always sternly opposed the idea of an appeal to the “whole people”, which includes the “rack renting landlords” and the “profit-grinding capitalists” and based himself on the interests of the working class.

In the run up to and during the rising he issued no separate platform setting out the socialist objectives of the Citizen Army. To have done so would have been no empty gesture, even in defeat. Had he issued his own platform making the call for a socialist Ireland he would at least have laid a foundation stone for future socialist movements. He would also have prevented political forces and individuals who represent the very antithesis of everything he stood for, from claiming his mantle.

Those who took part fought heroically and held out for a week against impossible odds. Connolly’s courage under fire earned him the respect, not just of the men and women of the Citizen Army, but of the Volunteer ranks and even of some of the British officers.

After the rising came the reprisals. The main leaders were court-martialled and executed. Connolly was severely wounded and in no condition to face a court martial but General Maxwell, the British General in charge, insisted that it go ahead in the military hospital. Connolly was sentenced to death and taken in an ambulance to Kilmainham jail where he was shot on arrival. It was the revenge of the British ruling class – backed by their Irish counterparts – not just for the rising but for Connolly’s lifetime of struggle against them.

The real tragedy of 1916 was clear to see just over one year later. In October 1917 the Bolsheviks led the Russian working class to power. The shock waves of revolution spread across Europe and beyond. Ireland too was convulsed by these events and a more favourable opportunity opened for the working class to take power than had existed at any time during Connolly’s life.

But Connolly was dead and in his death the Irish working class were deprived of their foremost and outstanding leader. Connolly had not recognised the need to build a disciplined revolutionary party and so there was no force present to carry on his work. The movement ended not in revolution but in partition and defeat.

Our tribute to Connolly is not to join with the false eulogies that will drip hypocritically from the lips of the establishment, but to learn both from his accomplishments and his mistakes so that the experience of his life will assist the current generation to succeed in finally ridding the world of capitalism.