By Manus Lenihan

“I want to denounce the subversive attitude [which is] absolutely politically financed by narcotraffickers, who aim to destabilize the constitutional democratically elected government.” These words were spoken in response to water charge protests, but they did not come from the mouth of some Fine Gael backbencher or posh journalist.

Irish anti-water charge protesters have been compared to terrorists, fascists and even ISIS, but the honour of being labelled a bunch of drug dealers belongs to the people of Cochabamba, Bolivia, who won a great victory against water privatisation in 2000.

Water supply privatised

In 1999 the Bolivian government insisted that privatising Cochabamba’s water was “necessary” to bring in private investment. In reality, the plan was about turning a public resource into a cash cow. The IMF and World Bank exploited debt to force countries to sell off their services and assets, just like the EU does today, and the Bolivian ruling class was happy to oblige.

Immediately, water rates in the city of Cochabamba went through the roof. Many people were suddenly paying one-fifth of their income for water. This was no accident or mistake – these huge price hikes were necessary if the new suppliers, the Bechtel Corporation, were to make the profits they expected. Maybe it would have been more skilful to start low, get everyone paying, and then hike the rates up gradually. But when it’s a question of corporate vultures doing deals with career politicians, greed, stupidity and arrogance are all part of the package.

Protests begin

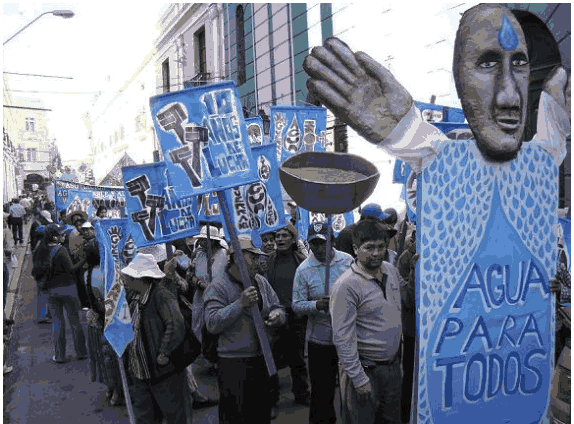

Bechtel and the politicians were in for a shock. A vast majority were against the new water plans, and protests started shaking the city. A coalition of trade unions, youth groups, left parties, farmers’ organisations and environmentalists led a militant campaign. This was a struggle based on mobilising the working class, small farmers and youth, not a strategy of waiting for a new government to come in and fix everything.

Diverse layers of society rowed in behind the workers – rural communities marching proudly under their village banners, retired factory workers, sweatshop toilers, street vendors and homeless children, middle-class people and university students. Protests escalated to a four-day general strike and a two-day battle with police.

Repressive measures failed

At one stage the government invited the protest leaders to negotiations – then, as soon as they had them in one room, sent in police and arrested them all! In April 2000 the highways of Bolivia were blocked by protestors. The government declared a “state of siege”, shut down media outlets, banned meetings, and began night-time raids and mass arrests. Around the country, several people were shot dead by police and many wounded by gunfire.

But all this repression failed. The protests put the government in a position where they had to give in. Bechtel was sent packing, and Cochabamba’s water supply went back into state ownership. In spite of the dire warnings about what would happen without privatisation, there has been no catastrophe.

Water wars electrified Bolivia

It’s important not to be complacent about the problems looming with the water supply in many parts of the world. But if we let them massively hike the cost of water for households or privatise the service, that doesn’t help the situation in any way. Bolivia shows how sustainability arguments are shamelessly abused by capitalists and their politicians. It’s one thing to see these arguments being used in a gigantic, land-locked, high-altitude, part-desert country. It’s ridiculous to hear the same arguments in our rain-soaked island.

Victory on the question of water kicked off a decade of protest and radicalisation, including the magnificent “Gas Wars” of 2003 and 2005, and the election of the country’s first ever indigenous president. It’s important not to romanticise this – the Evo Morales government from the outset refused to fundamentally challenge the capitalist system, and has increasingly turned to the right. But victory in the water war electrified the country and the whole region.

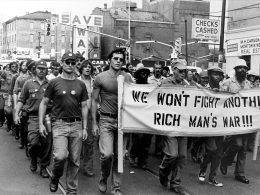

Workers and poor people in Bolivia have made huge gains. Sometimes in Ireland you hear people argue along the lines of, “If we beat the water charges, won’t they just cut us or tax us some other way?” Bolivia shows how a major working-class victory can turn around the whole political agenda and open up an opportunity for fundamental radical change.