The families of the eleven civilians who were shot and killed by the British army in the Ballymurphy Massacre in 1972 continue to campaign for justice. The workers movement has a duty to support their quest and to strive to ensure that the state is exposed for its crimes over the course of the Troubles.

The background to the massacre were the events of the night of 9-10 August 1971 when thousands of British soldiers invaded Catholic working class homes across Northern Ireland and 342 men were dragged away to internment without trial. The internees were assaulted and threatened, harassed with dogs, denied sleep and food, forced to run gauntlets of baton-wielding soldiers, burnt with cigarettes, and had gun barrels pressed against their heads. These techniques were later described by the European Court of Human Rights as “inhuman and degrading”, and by the European Commission on Human Rights as “torture”.

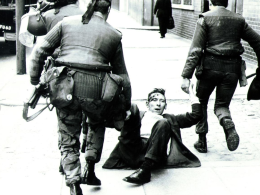

The communities which bore the brunt of this onslaught erupted. In the four days of rioting that followed, 20 civilians, two Provisional IRA members and two British soldiers were killed. 7,000 fled their homes. Roads and streets were blocked with barricades.

Of the 20 civilians who died, 17 were killed by the British Army. Three were shot dead in Ardoyne on 9 August, but the Ballymurphy estate suffered an even more vicious assault. There 11 civilians were killed by the Army in a 36 hour period between 9 and 11 August in an episode that has become known as the Ballymurphy Massacre.

Six were shot on 9th August. Nineteen years old Francis Quinn was shot by a sniper while going to the aid of a wounded man. Joan Connolly (50), Noel Phillips (20) and Joseph Murphy (41) were shot opposite the army base. Daniel Teggart (44) was shot fourteen times. Most of the bullets entered his back as he lay injured on the ground. The local priest Hugh Mullan telephoned the army base to say that he was going out to help those wounded. He came out waving a piece of cloth, walking towards a field where one of the shot men lay dying. He too was shot as he tried to help the man.

One civilian was shot dead on 10th August, and another four on 11th August. Edward Doherty (28), John Laverty (20) and Joseph Corr (43) were shot at separate points on the Whiterock Road. John McKerr (49) was shot while standing outside the local church and died of his injuries on 20th August. Paddy McCarthy (44) got into a confrontation with a group of soldiers one of whom put an empty gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger. He suffered a heart-attack and died shortly afterwards. There was no evidence that any of the 11 who died were armed or carrying explosives.

The soldiers deployed in Ballymurphy were 500 members of the Parachute Regiment, the same unit which shot fourteen demonstrators dead in the Bogside in Derry six months later. The recent Bloody Sunday enquiry report was firm in its conclusion that the events in Derry were unplanned and unpredictable. The report author Lord Saville said he could “not criticise General Ford for deciding to deploy soldiers to arrest rioters…” and that General Ford “neither knew nor had reason to know at any stage that his decision would or was likely to result in soldiers firing unjustifiably on that day.”

The evidence from the Ballymurphy Massacre is clear and contradicts his assertions. When the Parachute Regiment were deployed in Ballymurphy and on Bloody Sunday, senior army commanders and senior politicians knew exactly what they were doing. They sent in an aggressive regiment in an attempt to intimidate the residents in the areas that had become the greatest thorns in their sides. The soldiers clearly thought that they could get away with murder, and they did.

The Socialist Party has always condemned the paramilitary campaigns which caused misery for working class people. The state however was not a neutral arbiter and has much to hide. The ruling class, acting through the organisations of the state, will take whatever measures it deems necessary to protect its position and its privileges. Over the course of the Troubles it directed its sharpest repression against Catholic communities but was prepared to use lethal force in Protestant areas too.

In the future, the state will apply whatever measures it deems necessary when faced with revolts of the working class. A full independent enquiry is necessary to expose the role of the army in Ballymurphy in July 1972 and to make it much more difficult for the state to use these measures in the future.