By Stephen Boyd

In the wake of last year’s “Brexit” vote and the demand of the Scottish National Party (SNP) for a second independence referendum in Scotland, Sinn Féin first and now the SDLP also, have raised the call for the holding of a border poll. Stephen Boyd outlines the socialist case for opposing a border poll and what’s needed to overcome sectarian division.

Speaking at a Sinn Féin conference, An Agreed Future? In Belfast’s Waterfront Hall on 24 June 2017, Gerry Adams predicted a vote to end partition could happen within a “few short years”:

”We need a new approach, one which unlocks unionist opposition to a new Ireland by reminding them of their historic place here and of the positive contribution they have made to society on this island.”

Adams went on to say, “The Brexit referendum vote last year, the Assembly results in March, the Westminster election results this month and the census conclusions from 2011, are evidence of a shifting demographic and political dynamic in northern politics… within a few short years the potential for a vote to end partition and united ireland is a very real possibility.” At the same conference, unionist political commentator Alex Kane said “From my very personal perspective, the Irish unity debate has little or nothing to do with economic and structural cohesion. I hear the arguments about how we could “be better together” if we weren’t duplicating services across the island. But at the core of the debate is the issue of identity: who we are, who we want to be.”

There is a kernel of truth in Alex Kane’s argument. At the heart of the sectarian division in Northern Ireland is a conflict of national aspirations. Many commentators and nationalist politicians, however, argue that a united Ireland is now inevitable. They dangerously believe that all they have to do is come up with the “right” arguments to persuade Protestants to join a new united Ireland. This patronising and arrogant argument dismisses the national aspirations of Protestants and their genuine opposition to a change in the constitutional status quo.

Two sectarian headcounts

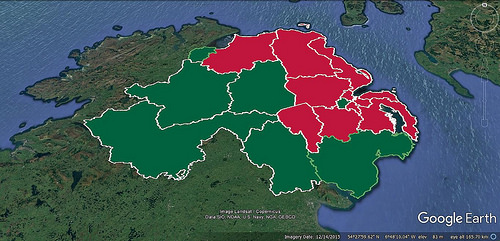

The ending of the unionist majority at Stormont for the first time since the creation of the Northern state at the last Assembly election was a political earthquake. Sinn Féin finished just 1,168 votes and one seat behind the DUP and on that basis predicted a vote to end partition in a few short years. Yet less than three months later in the general election, the DUP increased its lead over Sinn Féin to 55,000 votes, in an election that saw the biggest voter turnout since 1998. Voter registration was a feature of the general election with all parties focusing significant resources on getting “their” voters on the electoral register. And it worked. The DUP won ten seats and Sinn Féin ended up with seven, and in the process, they wiped out the UUP and the SDLP.

In Protestant working-class areas, turnout has been in decline for years as a result of growing disillusionment with Stormont, yet in this election, spurred on by the “threat” of Sinn Féin becoming the biggest party and responding to Arlene Foster’s rallying cry to “defend the Union”, turnout in some loyalist areas was over 70%. The election was a two-horse race, a battle between the DUP and Sinn Féin. Arlene Foster fought the election to “defend the Union”, Sinn Féin on achieving a united Ireland.

Both the DUP and Sinn Féin have been badly damaged by their ten-year partnership in government. The Assembly has not delivered for working-class people. Economically and socially, Northern Irish society has declined under their watch. The implementation of austerity by the DUP / Sinn Féin Executive has had a detrimental impact. Public services such as health, housing and education are in crisis. The threat to cut the school uniform grant to the poorest families is the latest in a long line of cuts that, along with the casualisation of employment, the scourge of low pay, a seven-year public sector pay freeze and a slashing of benefits, has left a majority of working-class people struggling to make ends meet.

The DUP have been badly damaged by scandals such as NAMA and RHI, and Sinn Féin collapsed the Assembly Executive in reality because they could no longer sustain the loss of support in their heartlands, which was a consequence of their role in government and being seen to not stand up to the DUP’s arrogant attitude and approach on issues such as funding for Irish language education.

Faced with this crisis, the DUP and Sinn Féin did what they always do when they are in trouble – they turned towards sectarianism in order to bolster support amongst their traditional base.

A changed situation

A new political period has opened up in Northern Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) did not resolve the underlying issues that have driven sectarian conflict on this island for decades. By promising all things to all people, the GFA simply postponed the conflict until another day. Power-sharing was always going to be fraught with difficulties. But when you have parties who depend on sectarianism for their electoral support and who have been implementing neoliberalism, then this current crisis was inevitable. The only way out of this morass is the creation of a genuine cross-community working-class party that can provide a real socialist alternative to the sectarian parties who are incapable of resolving the conflict.

James Brokenshire, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland speaking in Westminster said, “I have been very clear that I do not think those conditions [for a border poll] have been met.” A claim he repeated at the launch of the Tory Party’s general election manifesto. Nevertheless, both the SDLP and Sinn Féin have repeatedly called for a border poll. The Sinn Féin manifesto said:

“Sinn Féin believes there should be a referendum vote on Irish unity within the next five years… Ending partition has now taken on a new dynamic following the Brexit referendum.”

The UK leaving the EU has raised fears amongst Catholics (a majority of whom voted Remain, a majority of Protestants voted Leave), that a “hard border” will be a block to them achieving their aspiration of a united Ireland. Many nationalists also look to the EU as a form of guarantor of their human rights and a check to stop a return to the discrimination of the past. These fears are being played upon by Sinn Féin in order to rouse support for a border poll.

European Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, said the third priority in the Brexit negotiations was avoiding a border on the island of Ireland: “In order to protect the peace and reconciliation process described by the GFA, we must aim to avoid a hard border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland,” The Irish Times, 17 May 2017. If the UK and the EU fail in this aim then it can create the conditions for increased sectarian conflict and conflict with the British and Irish states. Aside from the potential economic impact of tariffs and custom controls on jobs and business, a hard border between North and South would have a detrimental impact on the lives of tens of thousands of people living in the border communities. Thousands commute daily back and forth across the border to work, to school, to visit relatives and even to use health services. Even “moderate” nationalist spokespersons such as Denis Bradley have spoken of a violent reaction to the re-imposition of custom posts and border controls, “If there is any attempt to construct a hard border I think the passions are so high that the people will pull it down,” The Irish Times, 4 July 2016.

Sectarian polarisation grows

Brexit has put the border centre-stage, but it’s not just Brexit that has created this situation – it would have developed anyway, as was shown by the two elections in 2017. The consequences of demographic changes are imprinting themselves on the political situation. Residential segregation has been a major feature of life in the North since the Troubles first erupted. Social housing is almost completely segregated and the expanding Catholic population in Belfast is creating the potential for new conflicts over territory, as was shown by the recent dispute in South Belfast over the erection of UVF flags in a new “mixed” housing development. The Whiterock ward, deep in the heart of West Belfast, was recorded in the last census as being 93% Catholic. On the Multiple Deprivation Measure (MDM) league table it is also recorded as being the single most deprived ward in Northern Ireland. The Shankill ward is 85% Protestant and ranks as number four on the MDM index.

Over the last 20 years, many commentators and some politicians have mistakenly talked of a decrease in sectarianism and have pointed towards the need for integrated housing, and education, as well as removal of the peace walls. There has been no progress on bringing down the walls that segregate communities as residents rightfully fear the potential for sectarian attacks. Polarisation between Protestants and Catholics has increased since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. There has also been little progress in the development of integrated education. Lagan College, the first integrated school, opened its doors in 1981, but 36 years later the enrolments for 2016/17 show that only 6.9% of children in Northern Ireland are educated together.

It is possible that by the time of the next census in 2021, Catholics may be the majority of the population. According to the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, the conditions may be met for holding a border poll within the five years envisaged by Sinn Féin. They and the SDLP have argued that their call for the holding of a border poll is “simply a matter of basic democracy.” This is a simplistic analysis based on the falsehood that to achieve their goal of a united Ireland all that is needed is a 50% plus one vote and to persuade Protestants that their future will be better in a capitalist united Ireland.

There have been a number of polls conducted in the last few years, including post the Brexit referendum, which all indicate a majority support for the North to remain as part of the UK. The last poll puts support for a united Ireland at only 19%. However all of these polls can be dismissed. They are shown to be meaningless by the result of the general election in June. This election gave us a glimpse of what a border poll would be like. It was the most sectarian election in a generation, where the electorate where given a stark choice. The DUP got its biggest vote ever for their call to defend the union and Sinn Féin received its biggest vote ever to give them a mandate for their united Ireland strategy.

Border poll will ferment sectarianism

A study of voting patterns published by the Electoral Reform Society in February 2017 showed that only 4% of Catholics would give their first vote to a unionist party and only 2% of Protestants would give their first vote to a nationalist candidate. In the event of a border poll the choice will be even starker – yes or no to a united Ireland. The voters will deliver a stark response with the overwhelming majority of the population forced to choose a side and the outcome would be the greatest manifestation of sectarian polarisation since 1921.

Catholics did not abandon their aspiration for reunification when they were a minority in successive elections over many decades. Their national aspirations encompass a belief that within a united Ireland, free from British rule, they will attain equality, security and a better economic future. Neither will Protestants abandon their desire to remain part of Britain if they become a minority.

Fears about the future of the union amongst Protestants have increased significantly since the March Assembly election. Nicola Sturgeon has put off holding a second Scottish independence referendum until after the Brexit negotiations, but that’s less than two years away and the potential for the break-up of the UK is a possibility in the short term. This heightened sense of anxiety amongst Protestants cannot be ameliorated by Sinn Féin’s skilfully chosen words and well crafted visions of a new shared Ireland.

The majority of Protestants wish to remain part of the UK because they see themselves as British. They also believe that despite the current economic problems they will have a more secure future as part of the UK economy, as well as placing a lot of importance on the existence of social gains such as the NHS. Protestants also, with good reason, don’t believe that the southern capitalist state can economically afford reunification and that it would jeopardise tens of thousands of jobs in the public sector.

Then there is the legacy of the Troubles. Thirty years of armed conflict has traumatised both sides of Northern Ireland’s divided society. The role of the IRA and Sinn Féin during that conflict will never be forgotten or forgiven by Protestants. Gerry Adams is living in a fools paradise if he believes that the anguish felt by Protestants, because of the role of the IRA during the Troubles, can be magically erased by clever chicanery. Protestants’ fear that they would be a persecuted minority in a united Ireland were confirmed for them by the armed struggle of the IRA, given the fundamentally sectarian nature of the campaign and the numerous sectarian atrocities carried out. Likewise a united Ireland dominated by the southern capitalist class would be incapable of upholding their rights, given the sectarian nature of the southern state.

Sectarian civil war

If a border poll was to result in a majority vote in favour of a united Ireland, it would not be accepted by Protestants. Subsequently, if the British and Irish governments attempted to move towards a united Ireland this would be resisted by Protestants and would create the conditions for armed resistance and potentially civil war, a war fought this time by Protestants in opposition to reunification.

The Socialist Party does not support the calling of a border poll because whatever the outcome, such a poll will result in a qualitative increase in sectarianism, and potentially could reignite armed conflict. The wrangling over whether or not to hold a border poll is now a dominant feature of Northern politics. If a poll was held and the vote was to remain in the UK then (just like in Scotland) political debate will centre on the holding of the next border poll and in the absence of a political alternative, politics will be poisoned by an ever growing sectarian divide.

The GFA was never going to succeed in overcoming the sectarian divisions in the North. The Socialist Party has consistently explained that the sectarian parties are part of the problem, not part of the solution and the GFA keeps the sectarian parties in power. If the DUP and Sinn Féin are allowed to continue to dominate politics in the North the outcome will be disastrous for working-class people.

The vast majority of working-class people in Northern Ireland are totally opposed to going back to the armed conflict of the past. The majority of them vote for the DUP and Sinn Féin out of fear of being dominated by the political ideology of the other side. This will continue until conflict inevitably breaks out again – unless there is an alternative built. The Socialist Party is opposed to the coercion of either community in the North. We oppose the coercion of Catholics into remaining in Northern Ireland and we are also equally opposed to the coercion of Protestants into a united Ireland. The right of no coercion of either side cannot be voted out of existence, which is what a border poll would do.

There can be no solution to the sectarian conflict on the basis of capitalism or sectarian coercion. The existence of capitalism is at the heart of the problems faced by working-class Catholics and Protestants. A strong cross-community working-class party has to be built to stand up to the DUP and Sinn Féin. This new type of anti-sectarian party can unite Catholics and Protestants in their common struggles against Stormont’s austerity and in defence of public services and for decent jobs with decent pay.

A socialist society: the only answer

The UK general election showed there is a growing surge of opposition to austerity and to capitalism. Theresa May’s weak government is floundering as anger grows against the public sector pay cap as well as the crisis in the NHS and housing. A wave of industrial struggles against the Tory government may not be far off and these struggles will not leave Northern Ireland untouched. In fact, if the last 40 years are an indication there will be a militant response from workers in the North. It is precisely these types of conditions that present an opportunity for socialists, community activists, trade unionists and those trying to rebuild Northern Ireland’s labour tradition to come together to form a new working-class party.

Such a party needs to be committed to struggling for a democratic socialist society, a new type of society that can guarantee a better life for all, a society within which the rights of all to live their lives free from discrimination and prejudice are guaranteed. It is in the unity built amongst and between working-class people in Scotland, Wales, England and in the North and South of Ireland in the struggle for this new society, that a socialist solution to the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland will be found by the working class themselves.n